Rakhshanda Jalil straddles being a writer, a translator and a literary historian, and is thus at a vantage to give us an unparralelled view of Urdu literature, Indian writing, the rise of translation, among several other things. We spoke to her about these and more – her journey as a writer, translator, Urdu literature today. Excerpts:

Over your 25 year-long career as a writer, translator and literary historian, you have introduced us to so many poets through your works, your articles, your interviews – invaluable in their contribution to Indian writing. Could you shine some light on Urdu fiction writing, and where it stands today?

Rakhshanda Jalil: There are some fine voices among the present group of writers – and I say this because I keep reading and editing collections of contemporary writings – but nothing that is comparable, say, with the Partition generation of writers who were active in the 1940s and 50s.

We are on the cusp of a change in Urdu literature. The literary canon is never cast in stone; it changes and re-invents itself just as literary tastes change and evolve.

That is the way it has always been. A great deal of good writing is behind us. Some very fine fiction writers have set the bar high. At present I am sad to say, a great of Urdu fiction is uneven, patchy. While this might sound like an awfully magisterial statement to make, I say this with empathy and concern; though some might think I am an outsider looking in considering I am simply a reader and a translator, not an Urdu fiction writer myself. But I am hopeful that this is a transitory phase; we are on the cusp of the next wave.

Could you point us to some lesser known writers of Urdu fiction?

- Ilyas Ahmad Gaddi from Bihar (author of Fire Area)

- Also Zakia Mashhadi from Bihar. Though, she’s being translated in English, and is now being read.

- Others who are very well known among Urdu readers but relatively lesser-known outside are S. M Ashraf, Shaukat Hayat, Abdus Samad.

You have been looking at Partition literature for so long – but in mainstream discussion, we see only a few literary names associated with it. Are there some lesser known writers whose work should be highlighted?

Rakhshanda Jalil:

Partition literature seems to be an inexhaustible fountainhead; it keeps gushing forth because the consequences of partition are still being felt through increasing communalism, sectarianism, bigotry.

Younger and younger writers are revisiting the partition if not directly as first-hand observers than certainly as people who are experiencing the consequences that unspooled from the events of 1947.

But among the ‘partition generation’ of writers, we need to read more and more of Krishan Chandar (because he wrote so much and has left such a large ouvre) and Hayatullah Ansari who has been somewhat overwhelmed by his contemporaries such as Manto. Other names would be: Fikr Taunsvi, Ramanand Sagar, Mahindar Nath, Kanhaiyalal Kapoor…. I can go on; like I said, so much was written and of fairly high caliber.

Over the last few years, translation has had a spotlight moment, and is recognized more and more.

Rakhshanda Jalil: Yes, it’s the sunrise industry! Everybody (and their aunty) is translating. Which is both good, and bad. The activity of translating per se is good; what gets published not always so. But overall, yes, it’s been a long journey and now we are reaping a rich harvest.

Has that affected things like remuneration, willingness of publishers to publish etc? To what extent?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Oh yes, translators get better advances than ever before. Less effort is required in cajoling recalcitrant or doubtful editors to take on works of authors, even the lesser-known ones. Book review editors want to give space to reviews of translations. Book shop owners have dedicated spaces for translations from the bhashas and from world literature. Literary festivals make speace for translations. There are even prizes with handsome prize monies dedicated to translations. All of which, taken together, is definitely towards a greater good.

There is a flip side to this as well – as more translations are available, the connection with the source language reduces. What are your thoughts on it?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Actually, I don’t see that as a problem. While I am concerned with the quality of translations (a problem of plenty!), I don’t see translations reducing the links with the source language.

If anything, more translations increase interest in the source language, help bring in fresh blood as it were. I know of many instances where people have been induced to learn the Urdu script after their introduction to Urdu literature through translations.

There is a popular Urdu course offered by the Department of Urdu in the University of Delhi (North Campus); a great many students from the Department of English who first encountered Urdu through translations opt for this course. I know people who have hired private tutors to teach them Urdu; most had encountered Urdu literature through translations.

Do you think Hindustani literature is seeing an impact, in terms of their popularity and accessibility, due to social media, ebooks and newer technologies?

Rakhshanda Jalil: We have seen during this prolonged period of lockdown how so many of us are discovering newer ways of communication, even those who are inhibited by technology.

Clearly, user-friendly technology, proliferation of social media, etc. can and will open up newer ways of accessing literatures. Already, the much-maligned whatsapp and other platforms are responsible, in a large measure, for the wider dissemination of poetry in particular; I think it is because a fragment of poetry combined with a visual element/motif and designed like a poster or GIF can serve to set a mood, express something pithy or topical, convey a brief message that longer works of literature cannot.

Of course, there are pitfalls; bad poetry is constantly being attributed to Ghalib or Gulzar (these two seem especially popular on whatsapp for some reason!) but that is because there are no checks and balances in the e-world.

But I will still say, taken in the balance, Hindustani literature has reached the nooks and crannies of the popular imagination in large measure due to social media in recent times in a way the print literature could not.

My sense is Urdu to a greater extent, and Hindi to a lesser extent, has still to embrace e-books or high literature. Publishers have made some tentative steps, especially during the lockdown, but we have to wait and see if it will catch on and whether it will have a life beyond the lockdown when/if the world rights itself.

Which are some of the contemporary translations you have read and admired?

Rakhshanda Jalil: I like everything I have read translated by Arunava Sinha from Bangla. Though I must confess I don’t read as many translations as I should these days.

For aspiring translators, what are the resources and tips you would want to share with them?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Close readings of the text with as few deviations as possible; fidelity to the text is paramount.

With fidelity comes great responsibility; one must acknowledge this is not YOUR work; it is someone else’s. As a translator, you are simply a facilitator. With time, I have understood that the facilitator too must perform many roles.

While earlier I was content to merely translate a text, I am increasingly keen to now provide a context too. I see that, too, as part of my role as a facilitator. Increasingly, now, I write introductory essays to my translations. I provide footnotes which many thought were unnecessary for a translation; a glossary of ‘native’ works usually suffices. But, no, I increasingly feel the glossary and footnote serve two different purposes.

A footnote allows you to expand the meaning and provide a context. It doesn’t clutter up the translation itself; it allows the reader to scroll down to the bottom of the page should she/he want that extra layer of meaning and information.

Writers movements in the past were very tied to the social movements. I may be very ignorant about this – but I have not read or heard about any formal writers movements in literary scene since independence or the years immediately after, even though revolutions small and big have taken place, and I think there is one we are going through – as we speak against the government’s anti-minority actions. Is that true? If yes, why do you think it is?

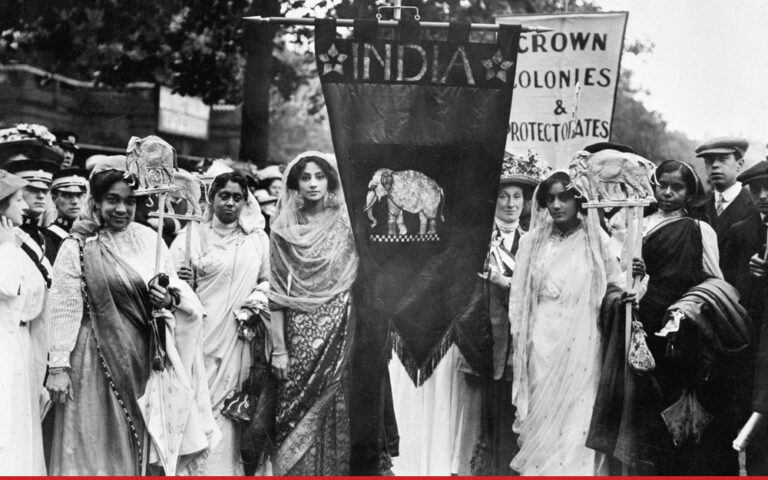

Rakhshanda Jalil: You are right insofar as we have not witnessed something as big and as penetrating (not just pan-Indian but all-embracing of the world) as the Progressive Writers’ Movement that raged from the 1930s till the late 1950s when it weakened as an ideologically-powerful literary grouping. Yes, we have had periodic bursts of resistance, be it for rights of tribals and minorities or resistance against forms of state-sponsored oppressions but they are largely in the nature of knee-jerk responses.

The ‘award-wapsi’ and the recent anti-CAA protests were by far the most cohesive. They brought more people together in a visible show of protest.

Some good poetry came out during the protests; I see Varun Grover’s ‘Kaaghaz Nahin Dikhayenge’ as an excellent example.

Some old poetry got a new lease of life such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s ‘Hum Dekhengey’ or Habib Jalib’s ‘Main Nahin Maanta’.

Popular Urdu poets such as Rahat Indori, Munawwar Rana, Javed Akhtar and Gulzar have all been active during this time.

I can point out Javed Akhtar’s ghazal: ‘Jo baat kehte darte hain sab, tu woh baat likh/Itni andheri thhi na kabhi pehle raat, likh’ and Gulzar’s haiku-like satirical series called ‘Murari Lal ke maathe ke bal nahi jaatey’.

Gulzar has also been very actively writing on the exodus of the migrant workers and their plight. But, sadly, these are all isolated incidents. We can not join the dots and see a discernible movement. Why that is so, I can not say. Possibly, the numbers are not adding up to form a literary grouping. They are all in the nature of cries in the wilderness. There is, still, not enough sense of common cause among the large majority of our people. There is, still, not enough outrage among ordinary people let alone writers for this to take the form of a movement.

You have written about writers meets during the Progressive Writer’s movement, how they would begin their meetings with a mushaira etc – what is the equation and vibe of writers’ meetings today? Is there the same sense of camaraderie and community?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Like I said above, a sense of community seems to be lacking. Till that camaraderie returns to writers, I don’t see any large, group activities where the literary fraternity comes together. Everyone wants the spotlight on themselves. Everyone wants to be the Chief Guest of the show. They come to speak; few come to listen.

How has literature’s relationship to academia changed, with humanities departments at large struggling for funding, and even students?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Really? My sense is more young people are drawn to the study of literatures and languages, even ‘obscure’ ones like Farsi.

If anything, I see a sense of adventurism among younger people that was lacking in my generation when people usually fell in with their parents’ expectations and ended up becoming doctors and engineers even if they wanted to be writers and poets.

Also, I see the gender ratio in Humanities departments righting itself with more male students opting for courses such as English Honours that traditionally drew more women students.

Are you working on something currently? Could you share some details with us?

Rakhshanda Jalil: I am always working on something…several things in fact at the same time! Too many irons in the fire but briefly: the collected works of Gulzar which I must finish soon but simultaneously an edited volume of Gandhi’s First Civil Disobedience Movement (1920-22) as reflected in the prism of literature, a collection of Bangla and Urdu writings on the creation of Bangladesh with co-editor Debjani Sengupta, four edited collections of feminist poetry for Vani Prakashan (Urdu poetry that has been transliterated in Devangri along with notes and an Introduction) and, finally, my very first novel in English!

One Response