Translation is a key political tool anywhere we go; but have the last few years of being in the spotlight changed things for the industry and how did Indian literature in translation become the latest buzzword? Payal Morankar finds out.

In a country that has hundreds of languages and dialects, it might seem that Indian literature in translation would be a default, always enjoying the spotlight. But that unfortunately has not been the case. For all our pride over India’s multiculturalism and multilingualism, translations have been underdogs of the Indian literary industry, lagging behind in the struggle for visibility and readership. The few that were published were mainly out of an idealistic concession for the social and cultural importance of translations.

And even within the limited number of works in translation, the first wave of translations from Indian languages to English was dominated by Bangla. The kind of novels that were translated were predominantly serious fiction meant for literary connoisseurs.

Over the past five years though, literature in translation has transitioned from the quiet dork in the background to the promising and popular new kid under the spotlight. It is not just getting noticed and cheered, but also betted on by the literary community.

“Translations are indeed no longer on the periphery; they have become mainstream and are altering the nature of our literary landscape. Their impact is not limited to our reading experience. They also influence our writing habits and the kind of stories we tell in any language,” says Arunava Sinha, award-winning translator, book editor at Scroll, and professor at Ashoka University

Translated bhasha literature has grown enough to become a large and distinct body of work in itself. Publishers recognise that translations require a different set of expertise, commissioning process, research, and marketing strategies. And they are no longer holding back on the resources needed to ensure the maximum possible quality and reach of translated books by having dedicated editors or separate imprints focused solely on translations.

Bookstores too have campaigns themed on translations, as do various literary pages on social media with special posts and features. #translationtuesdays and #translationthursdays be trending!

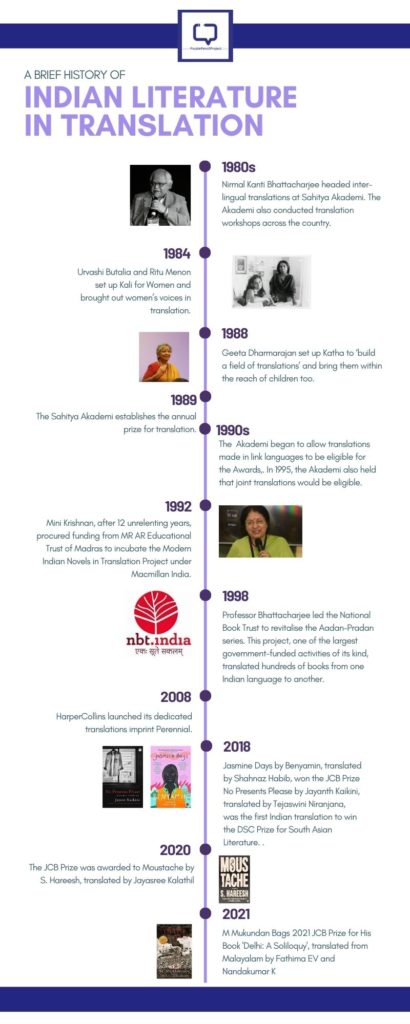

How did Indian literature in translation reach this stage?

Setting the stage

“As you know, nothing happens all of a sudden. The spotlight on translation activities actually predates the advent of multinationals in the Indian publishing scenario. I feel it was almost prophetic when Mini Krishnan stated in an interview in 2015 that no one setting out to publish translations today will ever know how difficult the terrain was 20 years ago. We may not know about their trials and tribulations much today, but we know what it all culminated into,” says Trisha Niyogi, publisher at Niyogi Books, whose catalogue includes such translations as Five Plays by Ritwik Ghatak, Land Lust, The Heroine and Other Stories.

Here is a brief timeline of the key moments in the journey of that story:

- 1980s: Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee headed inter-lingual translations at Sahitya Akademi. The Akademi also conducted translation workshops across the country.

- 1984: Urvashi Butalia and Ritu Menon set up Kali for Women and brought out women’s voices in translation.

- 1988: Geeta Dharmarajan set up Katha to ‘build a field of translations’ and bring them within the reach of children too.

- 1992: Mini Krishnan, after 12 unrelenting years, procured funding from MR AR Educational Trust of Madras to incubate the Modern Indian Novels in Translation Project under Macmillan India.

- 1998: Professor Bhattacharjee led the National Book Trust to revitalise the Aadan-Pradan series. This project, one of the largest government-funded activities of its kind, translated hundreds of books from one Indian language to another.

- 2008: HarperCollins launched its dedicated translations imprint, Perennial

Arundhati Roy in 1997, Kiran Desai in 2006, and Aravind Adiga in 2008 — some Indian writers in English won the Booker Prize in a short span of time. This caused other industry players to sit up and raise an eyebrow. If Indian writers can achieve such literary feats in a foreign language, bhasha literature must be rife with extraordinary stories and voices, surely? Multinational and trade publishers too began bolstering their own translation lists.

Since 2015, the literature in translation movement has grown at a steady pace, with surges caused by landmark books like Chowringhee, Ghachar Ghochar, One Part Woman, and the latest, Moustache.

“This ‘translation movement’ held its ground and gained momentum for one reason – translated books and stories are excellent. Also, now there are many new and young translators who are all doing an impeccable job. They read more contemporary works than classics, which is gradually changing the flavour of the portfolio of translated literature. The rise of translated non-English commercial literature will be the next big factor that propels translations,” says Sinha.

Translator stardom

Sinha is also among the most well-known faces of translation in India. He represents a parallel trend – that of translators receiving their due appreciation. From their names being mentioned just in passing, to having them front and centre on the cover, they have come a long way. Monetarily too they have greater bargaining power for their legitimate dues. In most cases, the royalty they receive for the translated work is equal to that of the author.

“Translators get better advances than ever before. Less effort is required in cajoling recalcitrant or doubtful editors to take on works of authors, even the lesser-known ones,” says Rakhshanda Jalil, writer, critic, and literary historian, who has brought several works of Urdu and Hindi, both prose and poetry, to English-language readers.

With a dedicated translations editor and translation list or imprint at almost every major publishing house, and several houses whose portfolio almost entirely includes translations such as Ratna Books, doors have opened for new translators to take up the craft. There are other avenues too, for them to hone their skills and get published alongside Indian English writers. Some such avenues are Indian Literature by Sahitya Akademi, Hindustani Awaaz by Rakhshanda Jalil, and magazines like Asymptote, Muse India, Parabaas, and Gulmohar Quarterly.

International recognition

The rise in popularity of translations is reflective of a global recognition of the value of translated literature in bridging countries, demystifying foreign cultures, and reinforcing the universality of human experiences in all its shades. Key developments that took place over the last five years have been:

- 2016: The International Booker Prize announced an award for a book translated into English to “encourage publishing and reading of quality works in translation and to highlight the work of translators”

- 2017: The United Nations declared September 30 as International Translation Day to “pay tribute to the work of language professionals”

- 2018: The National Book Award added a new category for translated literature to “broaden readership for global voices and spark dialogue around international stories”

And some translated bhasha works bagged some of these awards too!

- No Presents Please by Jayanth Kaikini, translated by Tejaswini Niranjana, was the first Indian translation to win the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature in 2018

- In the same year, Jasmine Days by Benyamin, translated by Shahnaz Habib, won the JCB Prize

- In 2020, the JCB Prize was awarded to yet another translated book — Moustache by S. Hareesh, translated by Jayasree Kalathil

- M Mukundan Bags 2021 JCB Prize for His Book ‘Delhi: A Soliloquy‘, translated from Malayalam by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K

“I believe that the recognition that the book has received on winning the JCB Prize would give it the opportunity to be better understood and read. I also feel that a platform such as the JCB Prize would foster more translations from Malayalam and other Indian languages into English and other languages.” — S. Hareesh, author of Moustache [My book will now be better understood, Edex Live, Nov 2020]

While awards remain a secondary goal for publishers, winning such accolades helps to increase a book’s recognition and gain more reviews. In fact, now translations are not only reviewed but also critiqued. A prize-winning title adds prestige to a publisher’s book list and inspires translators to nurture their craft further.

Literature, and numbers, in translation

Bhasha publishers have long focused mainly on their own audience. They were indifferent towards the publication and success of their titles translated into English or any other Indian language. But now some bhasha publishers, like Kalachuvadu Publications (Tamil), Mehta Publishing (Marathi), DC Books (Malayalam), and Anando (Bangla) are proactively offering their books for translations, making the very term ‘Indian literature in translation’ more inclusive.

The sales of translated work figures have certainly improved to a great extent, with some books doing a lot better than the rest, akin to any other genre. However, in comparison to Indian writing in English, the numbers for Indian literature in translation are still low.

“Though more of the youth is picking up translated books, it is still far behind in comparison to the international list. The increase in demand and visibility of Indian literature is not enough to convert international fiction readers to read Indian literature in equal measure. Global sales and recognition are crucial to achieve the level of Spanish and Japanese literature,” says Niyogi.

Despite the improvement in pay and recognition of translators, the lack of infrastructural support for their work has repercussions on the entire industry. Translators need a formal guild of sorts, which can provide them training, mentorship, workshops, collegial counsel, grants, and legal support. The impact of initiatives like The Yali Project has been limited, and the initiatives by Sahitya Akademi, poorly marketed. Translators still have to build and rely on their personal network.

In an age where few people have excellent command over their own mother tongue, a big challenge is that there are very few translators who can translate directly from one Indian language to another. This means they have to first wait for a book’s English translation before translating it into their own bhasha. Discovery of books for translation is delayed as a result. Translations editors too know only their own language, making them reliant on translators to identify and pitch books for publication. An active collaboration with bhasha publishers and encouragement to read vernacular literature beyond what is taught in schools is critical to make translation efforts more robust.

“To make translated Indian literature as globally popular as Indian English and other foreign translated works, we need to start reading it ourselves first. Players like Purple Pencil Project and Indian Novels Collective have initiated conversations on Indian literature among the youngsters. They can play a significant role in communicating the brilliance of the work available in Indian translations and break down barriers in their adoption, such as the notion that they are not up to the mark when it comes to subjects or ideas. For example, while mental health is a relatively new topic in Indian English writing, Brink by S. L. Bhyrappa and Avinash by Shanta Gokhale were written before the turn of the century. Queer literature too was written in bhasha works before the trend picked up in Indian English literature. There is still a long way to go. The work must go on,” says Niyogi.

Publish more and put the word out. Not just publishers but the entire literary ecosystem and Government bodies need to come together to encourage translators, create a natural sharing of world rights, and spread awareness among readers.

Translation as a political act

We cannot spread the magic of bhasha to a larger audience by treating it like an exercise to increase the market share of a particular genre of books; we need to approach it as a cultural change.

There is no refuting the importance of Indian literature in translation in binding our society. K. Satchidanandan highlights that Indian literature is founded on free translations and adaptations of epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata. From a literary standpoint, bhasha works have enchanting textures, astounding stories, unconventional voices, and delightful turns of phrases. And from a social perspective, they capture the ground reality and local flavour with greater precision.

“I’m not sure that a thing such as ‘Indian literature’ exists. There are many literatures from the geography of India which happens to be a politically unitary system, therefore we are a single market. But to truly unite the country in political terms, we need to translate cultures, of which books form just a small part. Why not also translate music, TV shows, street plays, YouTube videos, or just words? How about a local translation bar that lets you experience Goan culture by translating that region’s customs, folklore, and words even as you sip a glass of feni? Publishers, readers, educators, and entertainers alike need to unite and support a natural process of translation into English and other Indian languages. To go from being cosmopolitan to intercultural, we need to create a culture of translations,” says Sinha.

Some institutions and individuals are already heralding this culture, either consciously or purely out of their love for language. mothertounguetwisters is a translation project for Indian language and poetry; Rekhta is a comprehensive Urdu poem repository and dictionary; wordsinkashmiri showcases the beauty of Kashmiri words alongside its landscapes; thatteluguammayi shares her Telugu playlist with cultural contexts; and lyrically_obscure translates song lyrics and poems, of any language, that move her. There are many more such people doing bhasha’s good work, but we need to grow the ranks.

In these increasingly divisive times, we can draw from the power of language to dispel wariness and break walls. Whether it is Indian literature in translation or culture in translation, these initiatives should no longer require conscious effort but become instinctive.

One Response

Fascinating read!