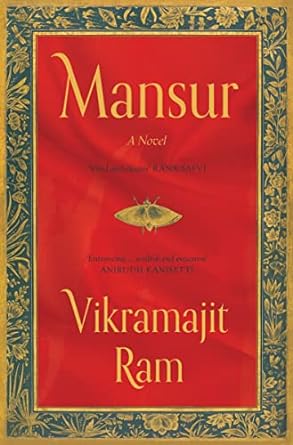

Rahul Vishnoi reviews Vikramjit Ram’s Mansur (Published by Pan Macmillan India, 2023)

Anirudh Kanisetti, the author of the Tata Lit Live winner for best book (non-fiction) 2022 in his promotional byte for Mansur, calls it ‘entrancing, soulful and evocative.’ It is indeed. All three of those.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Shortlisted for the prestigious JCB Prize 2023, Mansur by Vikramjit Ram is a novella set in a not-so-distant realm of once upon a time — the Mughal era, capturing a short and perhaps most important (fictional?) portion from the life of Ustad Mansur, a painter from the court of Emperor Jehangir who specialized in painting the flora and the fauna of the said period. Vikramjit Ram, in his interview with the JCB about his book, shares that although all the characters he has written about are real, his book is fictional. He is curious and talks about the human energy contained within all the art and sculpture around him.

Vikramjit Ram’s Storytelling and Writing

This is a book that took me to Google many times, and every time with a satisfying sigh. It feels surreal (and so wrong) to be able to appreciate a painting on your phone screen, snug in your bed, that Emperor Jehangir presented to Empress Nur Jehan on their wedding night. By the way, the painting (The Chameleon) is exquisite. The story starts with the titular character painting a dodo (the painting now displayed in Hermitage Museum, Russia), particularly the eye when he is interrupted by a fellow painter Bichitr.

Mansur is distressed. He can’t paint after midday as noon prayers have to be attended and westering light isn’t a good painting light. ‘The eye alone will take him an hour to paint.’ Moreover, he was supposed to leave for Kashmir the next day. Despite his reluctance, Bichitr insists on his time. Mansur’s inner turmoil at once establishes his sincerity and craftsmanship. He doesn’t want anything more than to get back to his painting but a small man wouldn’t let him do that. Mansur thinks: ‘From decades of studying furred and feathered beasts, Mansur has come to understand that, of the myriad emotions granted to sentient beings, discontent is the exclusive preserve of humankind.’

Mansur might have been awarded the honorific of Nadir ul-Asr (Rarity of the Present) after he painted a turkey by the Emperor himself but he wasn’t above the petty nitpicking and unwanted pieces of advice by the bureaucrats. Vikramjit Ram, who worked as a graphic designer, perhaps was inspired by the shenanigans of the clients in the art industry and he probably found his catharsis in the scene he wrote between a hugely-talented painter and a mere bureaucrat, the keeper of the paintings, who suggests the Rarity of the present to add some butterflies to the painting as the dodo looks ‘overwhelmed’.

Another interesting character here is Mirar, whose grandfather was amongst 176 painters ‘laid off’ by the Emperor when he came to the throne. Yes, the Mughals did that too! Murad is hopelessly smitten with his master Abu’l Hasan, Rarity of the age (it is these titles that are used to generate both humour and intrigue quite skilfully by the author), and wants nothing more than to be apprenticed by him. ‘Ambition, Mirar knows, counts for nothing in the absence of imagination and talent. He has ample blessings of both and the wits to keep them from abandoning him.’

The book has a few instances of sad humour. The zebra that was presented to the emperor was thought to be a painted horse and was tried to be scrubbed clean. The last remaining lion is tired. A flower boy decorated with flowers and asked to sit in the garden to compensate for the dried plants was shot by the emperor who was startled to see a plant move.

The book feels short. And it feels that Ram has kept it deliberately so. Like the tragically short life of its eponymous protagonist. Mansur lived for barely 34 years and the book foreshadows his death repeatedly, in the dialogues between Empress Nur Jehan and Mansur across a wooden screen who sometimes warms him ‘You had better not die, not before he finished what she had in mind for him.’

She also wonders was it true that the lifespan of a butterfly is a mere day. Birthed at dawn, dead by twilight? Why then, there were no fallen wings to be seen, the way we see dead petals and leaves? (Arundhati Roy, in her Booker-nominated second novel too wonders similarly: Where do old birds go to die? Why don’t the dead ones fall like stones from the sky?).

At the beginning of this book, it feels like you have arrived late to a lavish play, and in the end, it seems as if you have to leave because of unforeseen circumstances but this play will go on in your absence. There is a reason why the book feels that way. The eye of the dodo is still incomplete. The book, at some level, emulates the unfinished eye. Go look up Mansur’s dodo on Google.

Have you read this entrancing, soulful and evocative piece of writing? What do you think of it? Drop a comment below and let us know!