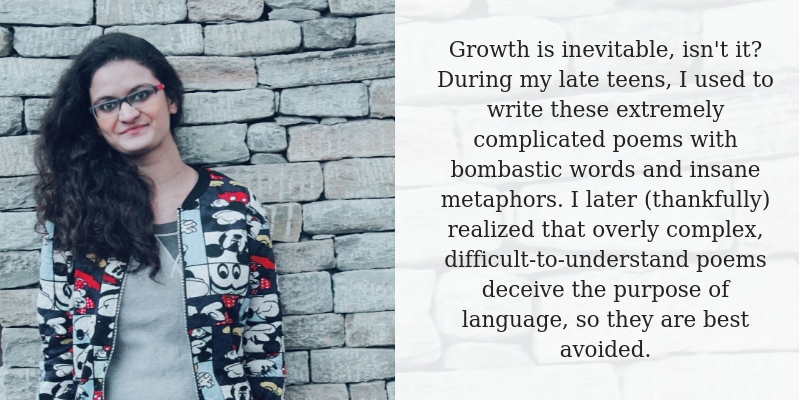

The Ethos Literary Festival 2018 takes place in Dum Dum, Kolkata, from December 22-23, 2018. From today, get to know your speakers better through our interview, as we understand their work and get a glimpse of the sessions they will be holding. First up is Nikita Parik, the 26-year-old poet with a Bachelor’s degree in English, an Advanced Diploma in French studies, a Master’s degree (MA) in Linguistics, and is about to earn another Master’s degree (MA) in English this year. Her works have appeared in Contemporary Literary Review- India (CLRI), Ann Arbor Review: An International Journal Of Poetry, Open Road Review Literary Journal, Shot Glass Journal, The Commonline Journal, Blackmail Press, and several others.

She spoke to onWriting about her journey as a poet, the use of language, what inspires her, and of course, what to expect from her session at the festival.

When Kiritiji (Kiriti Sengupta) introduced you in the email, he said “[she is] is a voracious reader and a critic but is often ignored for being young.” So I want to begin with this question: do you agree with him? Has your age ever come in the way of your professional and artistic path?

I think some senior folks might see us 20-somethings as very young , and that’s okay. I have always had a learner’s attitude- as long as I am learning things and growing, I am good.

From the time you wrote your first poem till today, how has your understanding of poetry changed?How have your stints – on the editorial team of ELJ and Virasat Art Publication, and your stints as India co-ordinator for the International Dylan Thomas Day and the Mujeres Poetas and as a member of the Intercultural Poetry and Performance Library – helped shape your view of poetry and poets?

Growth is inevitable, isn’t it? During my late teens, I used to write these extremely complicated poems with bombastic words and insane metaphors. I later (thankfully) realized that overly complex, difficult-to-understand poems deceive the purpose of language, so they are best avoided.

I do not remember my first poem, but it was probably about rain or nature in general. At that age, I was obsessed with monsoons and loved writing rhymed verses about the same.

Every single poem you study probably has some impact on you. I have been lucky to have been a part of groups like Rhythm Divine Poets and IPPL which strive selflessly to promote good literature. Constantly being in good company has an astounding effect on one’s growth curve.

As a poet, have you ever faced questions on your choice of career/path in life? Has anyone questioned the relevance of what you do? How does poetry fit into our modern lifestyles?

I have consciously never boxed myself into just one label. I want to write poetry anthologies, have a PhD, become a professor, and also translate French poems into English.

For those drunk on it, poetry is a way of life. For some, it is a coping mechanism, while for others, it is something that helps them make sense of their own selves. Poetry is essentially what you want it to be.

I have to ask this, what are your thoughts on insta poetry and, as Kiritiji mentioned to me in an earlier conversation, “the losing mysticism of poetry”, in today’s world?

To be honest, I am not a fan. But then, the reach and popularity cannot be denied for sure. Who knows, students of English Literature might study it as a poetry movement of sorts some 50-60 years later.

Has your understanding of Linguistics enhanced your appreciation of poetry?

Yes, I’d say so. When I read a poem now, the point-of-view of the linguist kicks in. For instance, I tend to identify and appreciate instances of internal focalisation or use of different poetic voices and personas more easily now. We are defined by the ways in which we use our language. It is a very intrinsic part of our identities. So it is very interesting to see the ways in which a certain poet uses her/his poetic language.

A lot has been happening in poetry – blackout poetry, spoken word. Which are some current global poetry trends that you are inspired by?

I wouldn’t say I am inspired by it, but I was recently asked to judge a spoken-word poetry competition at Indian Maritime University, an event organised by a group of spoken word poets. I was pleasantly surprised to see more and more poems on race, class, and gender. Spoken word, with whatever flaws it may have, gives a platform to young people, encouraging them to voice their politics. That, I think, is praiseworthy.

The poems I have read of yours all reflect a sense of love and loss. Do you consciously choose the theme? Or is it the emotion you most identify with?

Love and loss are very primal human emotions. Every single poem has a different story behind its making. So I guess it depends.

I see that Bengali words, and words from other languages, and perhaps cultural contexts, such as in this line

Like the tangy-sweet after-taste

Of white wine on an ashtami bikel.

They often litter your poems. Is this conscious a decision? If yes, why? If no, do you think it may have a limited appeal to readers?

I have been born and brought up in Kolkata, and I am so in love with this city. So it inevitably sneaks into my poetry, be it in the form of College Street boi-er-dokaan (book store) or kalboishakhi (Nor’wester) or Durga pujo. Likewise, since I am a Rajasthani, the poems that come from the space of what it is like to be from that land employ Rajasthani phrases. Often, certain phrases in our native language(s) have a charm that simply doesn’t exist in their translated versions (if they are translatable at all, that is).Then again, there are certain experiences in this part of the world for which there are no English words at all.

There are punjabi poets writing in English who strictly refrain from using capitalizations or punctuation because the Gurmukhi script doesn’t have lower/upper case-distinction, or punctuations like semi-colon etc. Can this be seen as a conscious break from the tyrannies of the colonial language, and an attempt to create a language that is more in sync with their mother tongue?

It is how you choose to express yourself, and how you transform the language of the colonisers and make it your own. There is no one ‘English’; rather, there are ‘Englishes’. Your language is the voice of your politics. If your morphological and syntactical experiments are in sync with your linguistic politics, and you have a good enough reason behind it, I don’t see any problem.

Besides Plath and Sexton (who are reflected in your poems), which poets inspire you? Could you share with us one poem that you go back to whenever you need that little boost in life? Are there contemporary poets whose work you admire? Could you give us some examples?

The thing about inspiration is that it can come from the unlikeliest of places. A phrase here, an interesting metaphor there, a stunning enjambment somewhere. I read a lot of poems, some of which may come from very famous poets, and some from budding writers.

There are so many poems that I love. One of them is “The Song of Kamala Sundari” by Nabina Das. It’s absolutely stunning. Among the contemporary poets, I love the works of Nabina Das, Arjun Rajendran, Mihir Vatsa, Sanjeev Sethi, Kiriti Sengupta, Sumona Roy, Arundhati Subramanium, Amit Shankar Saha, Manjiri Indurkar, and so many more!

I have seen that you often refer to the ‘I’ in plural in your poems. Is that symbolic of the many selves we embody, or is there another meaning to it?

Yes, you’re spot on! It does refer to the many selves we have.

Lastly, what can the audience expect from your sessions at the Ethos Literary Festival 2018.

I will be speaking on female aesthetics in literature, especially poetry, alongside Dr. Srividya Sivakumar. So one can expect a discussion on gynocriticism, the evolution of L’ecriture feminine (“female writing”) and female aesthetics circa the second wave feminism, and what it means to have a writing that originates from an essentially female experience.