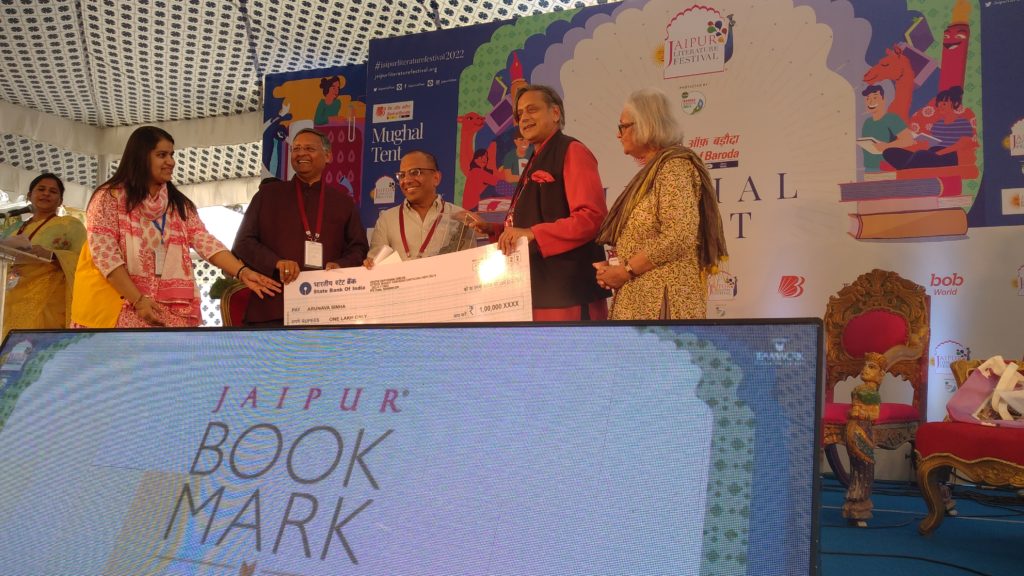

Arunava Sinha, winner of the Vani Foundation Distinguished Translator Award at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2022, spoke to us about being a translation practionery, juggling several roles, his favourite forms of entertainment, and much more. Excerpts from a transcribed interview.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

You have been working constantly at the heart of the book industry – 66 translations, with the Center for Translation, now with a direct to author publishing model you are experimenting with. I think of your approach of also being infrastructural – filling gaps in infrastructure. Did you start out knowing these gaps? Do you consciously pick projects and concepts to fill these?

Arunava Sinha: Translation, of course, is an ongoing activity and I guess every untranslated book is a gap, in that it’s not being read by people who don’t read in the language in which it was first written. But the other things are things I’ve become interested in, by virtue of being a translator and also by virtue of running the books’ pages on Scroll.in. So when the founders of Scroll set up this new platform, where their idea was for writers to try and reach out directly to readers, I thought it was very interesting and worth spreading the word about.

You have been a translator – and now you are working on developing it as a craft – as a course. How has your own approach to translating changed as you delve more into translation theory perhaps or engage with it as a technique?

Arunava Sinha: No, I’m a practitioner, so, I teach the practice of translation. But, of course, as you translate, you also develop certain principles and ideas that arise organically from the practice. So I do talk about those in my courses, they help people take decisions in translation, it’s so much a matter of making the choices. So what principles do you use to guide your charging when you translate this word or that, this sentence or that. So if you have certain unstated rules as it were in your head, it helps. So that’s how I won’t call it technique, I would call it perhaps some principles of practice.

So it’s an often asked question, but what is your priority while translating? Is it fidelity to it? Or is it bringing on the essence whether it’s not exactly matching what the author said?

Arunava Sinha: So the idea of the essence is a very dangerous one, because you’re taking a really rich text, and you say, this is the essence of this text, and then you’re probably reducing it to something. It’s up to the reader to figure out what a text is. As a translator, my job is to allow the reader, in a new language, to have all the possibilities that the reader of the text in the original language has. So if you can interpret a work in 50 different ways in Bangla, the English translation should be fully interpretable too. My job is not to interpret, not to reduce it to this meaning or that meaning, and therefore not to prioritize, but to capture everything that I get in when I read the Bangla text. I want to capture all of it and make it available.

Tanuj Solanki asked this question in an earlier session (at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2022), of the code-switching between languages that takes place when we sit to work in two languages. Do you need to replace your bedside books from English to Bengali? What is that like? Or in your case, from teaching to translating? Or translating adult or children’s fiction? What is that process of code-switching like?

Arunava Sinha: There is no switching, it’s one continuous existence. It’s different facets of the same. So when I’m teaching translation, I’m not a different person or approaching it in a different way. I’m just taking certain things out of that practice and talking about them. Similarly, when I’m translating for children, I’m not doing it in any different way, I’m letting the text speak for itself. If the text, that I’m translating, has chosen a particular way to talk to children, so will the translation. But it’s not that I have to keep in mind that this is meant for children.

And what are you currently working on, as of now, any projects that you have?

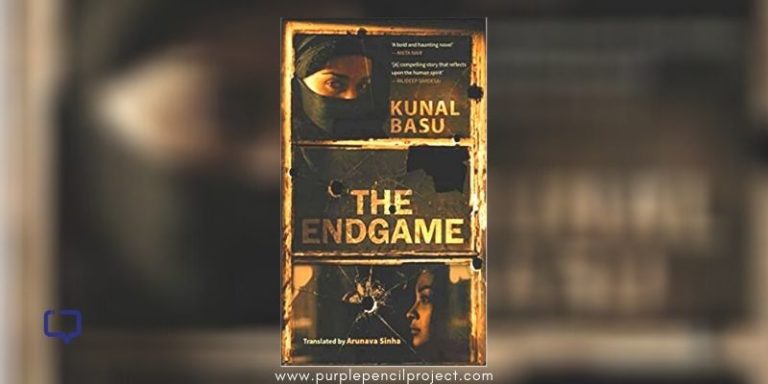

Arunava Sinha: Yeah, there’s always a project that I’m working on. Right now, I’m finishing up a book of autobiographical essays by Sankar, the Bengali writer. His was the first novel I translated 15 years ago. Well, that came out in translation 15 years ago.

After all this, do you get time for leisure reading – non-working related? What are the other forms of storytelling you enjoy and engage with?

Arunava Sinha: For one thing, you can’t be a translator unless you’re reading a lot. And I read for pleasure, I always have. So certainly, I make the time for reading. And I don’t watch too many films, but if I’m being taken by the idea of a particular film also, I do watch it. I watch football, on television or the reruns afterwards. There’s a dog at home. So that’s a major form of entertainment.

Last question, so what do you think are the Bangla texts that are quintessential, because I think it’s probably the most exhaustive literature in Indian scenario-

Arunava Sinha: We all think that about our languages, but certainly one of the most richest, no doubt.

– so what are the books that you think are essential steps to have a foundation, in your opinion?

Arunava Sinha: So I’m very opposed to the idea of a curriculum, you should read what appeals to you.

Some favorites atleast?

Arunava Sinha: It changes over the years. But I would say that if you want to do justice to a relatively underrepresented side of Bangla literature, read women writers. Read the women in particular. Read the marginalized writers in particular. Because the mainstream writers have all been read and people are aware of them, but perhaps it’s the people who are writing not so much at the center of the publishing world, who have many, many more interesting and valuable things to say.

As part of our effort to compensate our writers better, we at Purple Pencil Project have launched the #PayTheWriter initiative, where readers can directly show support and appreciation for our wonderful team.

Scan or upload this image on your UPI app, and show them the love 😀