“Contemporary Indian literature seems to be too focused on the human world, and seems to have forgotten the world outside it,” said Amitav Ghosh, at the book launch of Gun Island in Mumbai.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

His latest is a cli-fi (climate fiction) as they call it. Yet, at the end of this rather well-plotted saga, which tries to traverse the boundaries between what we know and what we don’t, science and myth, logic and belief, politics and climate, and more, you cannot help that the human focus cannot really be taken away.

The premise is that myths live on, among us and around us, only if we care to look and dare to follow the stories. The theme is that humans stand to lose the most with changing climate patterns, resource depletion and more and that we should once more, as we have before, build a bridge between what is human-made and what is natural; and of course, believing in stories is the way to do so.

Open at the close

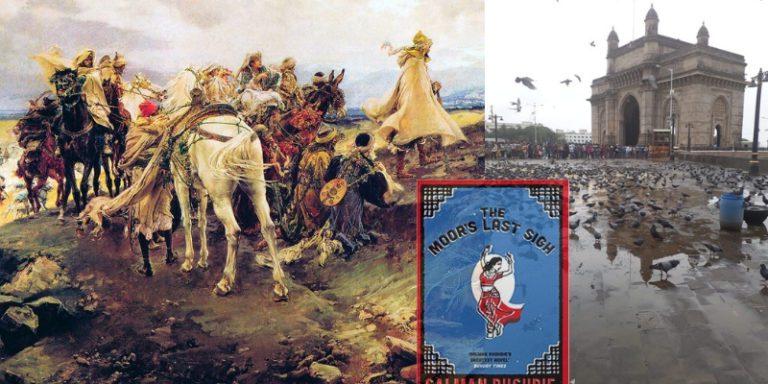

Ghosh begins Gun Island (Bonduk-dwip) with the myth of the Gun Merchant of the Sundarbans, who, to defy and escape the goddess Manasa Devi (pronounced Manu-sha Devi), who ‘rules over snakes and all other poisonous creatures’, travels around the world to escape her, only to return and build a shrine to her.

Dinanath Datta, a Bengali-America ‘rare books dealer’ is on an annual trip to Kolkata, India, where an old friend tells him this story, as told to him by his aunt Nilima Bose. “She wants to talk to you about the shrine [of Manasa Devi in the Sundarbans], she thinks you’ll find it interesting.”

What ensues is a continent-hopping story to piece together this legend of the Gun Merchant (set in the 1600s. How our characters arrive at this date is an interesting detail of the book), which takes him from Kolkata to the mud swamps of the Sundarbans, back to his home in Brooklyn and finally, to Venice.

This journey is not often voluntarily taken; Datta or Deen is almost always on the verge of returning to the comfort (or discomfort) of his routine life in Brooklyn, and always it is some external force that pushes him to pursue it. First, it is Piya’s (making a return from The Hungry Tide) company he seeks, then his friend and Italian scholar, Professoressa Giacinta Schiavon (or simply, Cinta) aids and pushes him along.

With him on this journey are characters, events and mysteries that tie this saga into an interconnected whole, and present a view of the world as one inhabited by not just humans, but animals, mud, rain clouds and wildfires, trees and ‘ghosts’, and more.

The nature of history

The story of the Gun Merchant is first told to Deen in fragments; by Nilima Di and then by Rafi, whose grandfather was the caretaker of the shrine to Manasa Devi, on the walls of which there are episodes and symbols from the travels of the Bonduki Sadagar.

This tale, as most, has not survived in its entirety and Deen does not know how to make sense of it. But together with Cinta, they deduce how Italian words came to Bengal, through time and trade routes, and piece together the exact location of the Gun Merchant’s whereabouts in Cinta’s city of Venice. These passages are a nerd’s delight, and the reader will enjoy seeing how words play around.

Ghosh’s use of historical details is not new, but in this, he combines the history of the land, and climatic history (the Little Ice Age is a marker of time) with that of the characters and presents a more wholesome picture. There are references to trade routes, architecture, to politics, commerce, currency in use, etymology, and mythology – and you realize that understanding history is like painting a white egg on a white canvas. It is possible only if you depict the shadows and colours that play around it.

Yet, it does not always read as a whole. At every stage, it is either chance or a ‘sign’ that moves the plot forward, climate hovering as a compulsory plot device, sometimes forced, not in how it should be narrated but how it is written. The climate and the fiction halves of this cli-fi are not always seamlessly combined.

The nature of people

In the Sundarbans, Deen meets Tipu, the computer whizkid who is comfortable speaking about buying and selling humans as a trade, and who embodies the essential message of the novel – that the natural world and the human one are connected, we only need to know to bridge it.

Here he also comes in touch with the reality of the dying sea life due to the chemical waste from a plant, the knowledge that the people of such areas have nowhere to go, and that freedom often comes at great cost.

Then there is Rafi, and Cinta, and Piya. Criticism must be made of the slightly flat narrative arcs for both Piya and Cinta, which are unimpressive, especially because Gun Island gave them such scope to be more than what they began with. Much like our Deen, Tipu, Rafi and Manasa Devi’s characters whose journeys are worth noting.

Most other characters get a passing reference, and a side role at best, be it Gisa, Nilima di, Lucia, Moyna or others.

Cultural, religious and class differences, the role of the internet in bringing agency to people’s lives, and the pressures of migration; you will meet all aspects of human life, as you see it and read about it.

The nature of land

For readers of contemporary fiction though, it is the nature of the land in Gun Island that will most enliven your reading. Whether it is storming being used as a measure of time, or references to cyclones such as Aila and the changing waters, thus, changing markers of land, the land is always a part of the narrative.

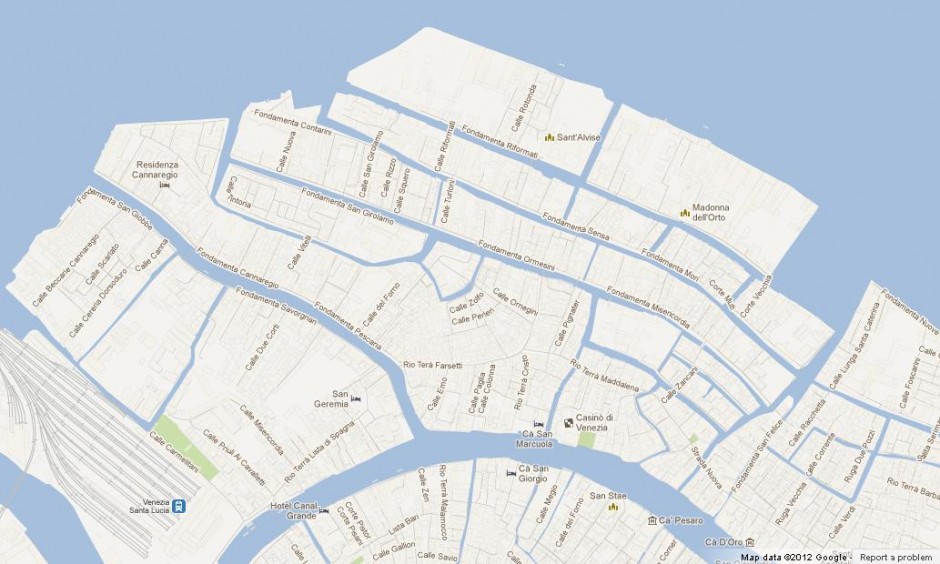

Venice itself is described in cartographic detail, so it helps to refer to this map while reading it.

In Venice too, it is the buildings that are somewhat ‘alive’ in that they make creaking noises and seem to be breathing of their own, in LA, it is the wildfires and finally, it is in the workings of nature outside human understanding and human rationale. And these lands are not divided as on human maps, patterns and similarities in geography are often found (Shubhangi Swarup’s Latitudes of Longing explored this idea last year)

At some point, Piya says, “You’ll hear those words often here. We’re in a new world now. No one knows where they belong any more, neither humans nor animals,”

The discerning reader will feel helpless, not for the humans, but for the rest of the animal kingdom, who do nothing. Only try to adapt.

Animals play equally, if not more, important roles – be it snakes, whales, dolphins or birds.

Conclusion

Ghosh is a master storyteller – you don’t need to read this review to know that (special note to how he begins his chapters). In Gun Island, he really weaves a wholesome tale that is, however hard he tries, still leaning towards the human. Perhaps that was deliberate, much like all the co-incidences that lead Deen to the end (which start to get too much at a point), or perhaps our worldview has become so anthropocentric, that even something as real as a climate crisis can only occur in the background.

At some point, a question arises about what Jacobean drama had to do with the weather. If all art is a product of its times, then Gun Island is a perfect response to the destructive world we live in, and for that, it deserves all our attention.

“If mere words could have this effect, what of the pictures and videos that scroll continuously past our eyes on laptops and cellphones? If it is true that a picture is worth a thousand words, what is the power of the billions of images that now permeate every corner of the globe? What is the potency of the dreams and desires they generate? Of the restlessness they breed?

Recommended for: All readers, but perhaps leave the young ones out, if you want to protect them from the fear of the world coming to an end.

Suggested Readings:

- Read this article on rare books in India, for kicks

- Read this fantastic feature in The Hindu about how weather changes affect the lives of Malabar fishermen

- Chinatown Days by Rita Chowdhury, to understand the lives of migrants

- The Hungry Tide, by Amitav Ghosh, for a Sundarban reading experience

- Migration realities currently prevalent the world over

Additionally, you should watch Moana, for a story that is equally wholesome on how life, history, myth, culture and humans interact with each other.