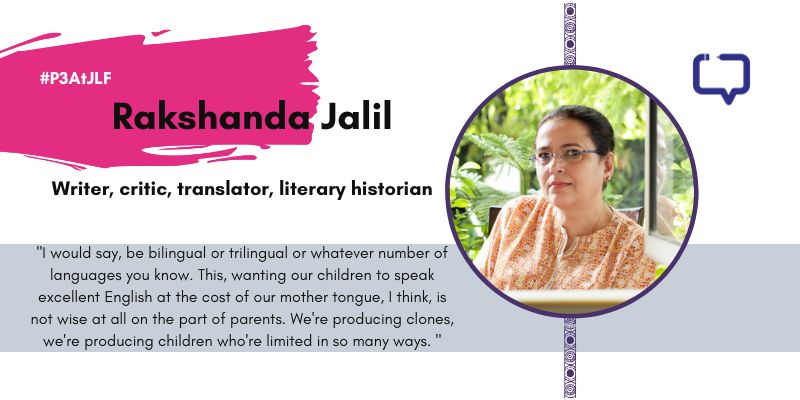

Rakhshanda Jalil is an Indian writer, critic, translator, and literary historian. Jalil runs an organization called Hindustani Awaaz, devoted to the popularization of Hindi-Urdu literature and culture.

Excerpts from an interview, conducted by Prakruti Maniar and transcribe by Amritesh Mukherjee.

How is it to be back for live events on ground?

Rakhshanda Jalil: I think we should always aim for live interactions. Speaking for myself, I’m a self-employed, independent writer, researcher, translator (and) I think it is a very lonely business. It’s all very well saying books are great company and all of that. Indeed, they are. But every now and then, you wish to step out of your home, your comfort zone, and you need to go out, meet people. I think lit fest gives you that opportunity.

What the pandemic did was that it made many of us, well, celibate in the sense that we became extremely, extremely insular. But I think we need cross-fertilisation, you need some sort of interaction. So I quite like the contrast.

Truly. I have been attending the poetry-reading sessions and thinking; this cannot be enjoyed online…

Rakhshanda Jalil: Absolutely, you can’t be reading poetry into a little window on your laptop, you know? And you do need the wah-wahs, you do need the nodding heads, you do need that beatific smile on somebody’s face, because something somewhere has struck a chord with that person. And why just poetry, any of these sessions that we’ve been having, it delights you when you see somebody nodding away vigorously.

We have spoken about your role as a translator and about translation, earlier. I want to turn to your life as a historian, and the problems of access for researchers in India; journals, library resources etc. Have you experienced it?

Rakhshanda Jalil: Indeed, I miss the fact that, in my last job, a think tank, there was easy access to journals. It was just a click away, because they were institutional buyers of that software, which allowed me to access journals. But fortunately, living in Delhi, I’m able to access many of these things through libraries of which I’m a member, who in turn have access to these.

Something I wish to share with businesses and researchers is this remarkable library network. It’s in different cities and would be called Delnet in Delhi, it would be called BomNet in Mumbai, CalNet in Kolkata, and so on. It is basically an Interlibrary Loan network.

If you think you want something on, let’s say, the Progressive Writers Movement, you just enter “progressive writers movement” in the search engine. And whatever books are carrying that title, carrying it as the subtitle, or are about it, (they) will show up in the database of all the libraries that are linked to it. So let’s say, for the sake of the argument, that you have a book that you need, in a locked non-lending library in Delhi. Let’s say you have that book in a library, but it’s in Surat, or Baroda, or Ahmedabad, right? You can still put in a request and all you need to do is pay for a courier.

We are actually so quick to diss our institutions and our systems, and every now and then they surprise us. It’s incredibly helpful for independent researchers like myself, with no institutional support, no scholarships, no fellowships, none of these things, which give you that little extra smoothing the path for the rigors of research. We are always on the lookout for these other things that are otherwise institutionally linked. For instance, I’m a member of the Indian International Center library, I just go there, and I use this interlibrary loan.

People are minting money by sharing such resources, whereas I think there ought to be a sorority and a fellowship amongst broke writers and researchers.

And research is so crucial, yet no one pays you for your time and effort spent researching. Just the word-count…

Rakhshanda Jalil: That’s true. Fortunately, I haven’t worked for people who pay you by the word because I think that’s really, really ridiculous. You cannot be paid for the word, even as a translator. What about the research, the routine, the backstories, the ones that you carry in your head, or those ones that don’t show in what you write, but nevertheless, influences your writing? It’s man hours, woman hours, that you put in. So there is all of that.

Also, this business of negotiation, I’ll speak for myself here, I don’t know how others do it. I do two kinds of work, one that I’m very passionate about, and I’m willing to do for a lesser cost. Others that are paid with token amount, it could be an amount for a column, those I cannot negotiate, because they are actually laid down by the journal or newspaper.

But every now and then, there’s a third kind of writing I do, and this is very seldom, and this is only when I’m feeling very broke, and then I feel that, then you ought to be a shark. And then you really need to sniff out the blood, and then you need to go for the money. So let’s say it’s a commissioned book, which I don’t do ordinarily, only when I need to finance the rest of my work. When you take up such a project, you (must) be a shark and ask for some serious money. I mean, I’m not Chetan Bhagat. So I cannot ask for that kind of serious money but something that sees me through, to compartmentalize.

The challenges of being your own boss, so to speak…

Rakhshanda Jalil: Yes. This is a life one chooses, one could have stayed on in a regular job and being this person who gets a pension and provident fund and all the rest of it. One chose, for whatever reason, to opt out of that. So, of course, it comes with its own problems, and money is the biggest one. The second is also, what I mentioned early on, the isolation, how insular you become. There are days you miss office gossip, bitchy bosses, nasty colleagues, the gossip around the watercooler, the coffee breaks, all of that you miss. So, of course, it’s a lonely exercise, but it’s also a choice. Then you cannot gripe about it because you chose to be this person who’s happily broke, who can up and leave, go to places.

You don many hats, all of which come back to writing, research – but different kinds of it. How do you manage all the notes, the research that’s mean for the individual projects.

Rakhshanda Jalil: I have multiple projects going, so it’s not possible to keep everything in my head, though I like to think that I carry most of it in my head, but I do not. I do have organizers, I have these nice folders, where I can put things, put labels. Because I have multiple projects, my workstation is a sea of envelopes and files and transparent folders and stacks of books at any given point. My bedside table is also a mess because the stuff that I keep, and my bedroom, which is an extension of my study, has books, papers, notes, yellow stickies, all over the place.

I think these are things that your family, your partner, your children, they accept about you because this is who you are. So they are used to the fact that the living room, at any given point, will have a stack of books that they have to negotiate around because the books are not going to go anywhere. They are the ones who need to make space. So I think it’s also the people who you have in your life who need to work around the fact that you are a writer, you may not have regular hours but they have to live with it. That’s all.

This is such an important thing, especially as work from home has become the norm; how those around you adjust to it. Even in terms of the privacy and space you need but may not have access to – not everyone understands that just because you are staring at the screen, it does not mean you are not working. Your mind always is.

Rakhshanda Jalil: That’s right. You’re in the middle of crafting a sentence. You know, one shouldn’t take writing lightly because writing is a thought, there’s a process that is a chain of thoughts. So that snaps because somebody just decides to come and say there’s a courier at the door. So you handle the courier, you handle the groceries that have to be bought, you’re running the house, you play Mommy, you play all your other roles, and along with that, you do the business of writing. So, I think, especially when you are self-employed or you are not in an office, people come home at five and they say I’m not going to work after office hours. Of course, in the pandemic, people have continued to work at all odd hours. But for a writer/translator, there is no 9 to 5, at least for me there isn’t. I do work at any given point. So the rest of the family, the household, has to work around that.

Juggling these roles, this constant switching of contexts. Is it not exhausting, or difficult?

Rakhshanda Jalil: I think I must be having a circuit that’s wired differently. Because I seem to do this all the time. Right now, I’m here, the Jaipur Literature Festival, and I’m lit festing, talking to you, but five minutes from now, I’ll be putting out posts about this Urdu festival that I’m curating and conceptualizing. I did some in the morning but I need to do it all through the day, and in days and weeks ahead. On the 20th of March, I will be organizing this day-long celebration of Urdu. We do it every year in Delhi, in a place called the Habitat Center. It’s called Afreen, Afreen. And the idea is to celebrate Urdu and Urdu Poetry and literature through curated sessions, themed based sessions. So yeah, I threw up many balls in the air and managed to catch some. I possibly dropped many. But I think the joy is in the throwing of the balls, as variegated, as colorful, as one can.

Let me share an incident from my life. About 15 years ago or so, I decided to do a PhD for no particular reason. I was in my 40s, I had a house to run, I had two children, a husband, all the rest of it. But I decided I needed that year off to write the thesis. So I rented a little cubicle in the Indian International Center library. I would go there at 10 o’clock, and I would work all through the day. I’ve done my research till that point, which required going to archives, museums, and libraries, (it) all happened, it was the question of sitting down and writing. So there was this cubicle, which is 6 by 8, which I had rented, and where I started from 10.30 till about 8 when they said okay, now it’s time to go, we’ll lock up. I’d come to my house. So this was research-based writing, which was very, very (complex and involved) cross references, footnotes bibliography, you know, you don’t write out a sentence without providing a cross reference, for a thesis.

And then I would come home, I would have dinner, sort-of catch up with what was happening. And towards the end, say, from 10 onwards maybe, I would write fiction. So you talk about the hardwiring of the brain, I don’t know how this happens. And from this relentless footnoting, and, you know, PhD sort of writing, I would switch automatically to writing fiction, which has no footnote, no bibliography, nothing, it just has what you have inside your head, which is coming out in some form through words.

At some point in one’s life, one feels as if on an adrenaline rush, that is the only way to explain it, no other way. Because to do two such different writings, and in that same span of time when you’re doing your thesis, which is a totally different kettle of fish for anybody who’s done a PhD. And then to do these short stories, which were very different, and not even remotely connected to my PhD. So I think that was also a very interesting time for me personally, but it taught me that one can do multiple kinds of writings, so now, I might be writing an op ed, I might be writing a column, I might be writing a book review, part of my own work or as a translator. Even as a translator, it could be translating poetry only, it could be translating prose, another. All these things are required, but what is the common thing? The common thing is our words. So how we utilize those words, so be it translations, op eds, or journalistic writing, at the end of the day, it’s words.

Speaking of words; we have to talk about the constant tussle between English and our mother languages. As a translator and parent, how do you navigate that?

Rakhshanda Jalil: I would say, be bilingual or trilingual or whatever number of languages you know. This, wanting our children to speak excellent English at the cost of our mother tongue, I think, is not wise at all on the part of parents. We’re producing clones, we’re producing children who’re limited in so many ways. Because I think the emotional quotient of children, who spend time with grandparents or extended family members, I would like to believe, is higher than those who are in nuclear families and raised into a mono culture. So I would say that tourism, diversity of culture, languages, multiculturalism, multilingualism, all of these things are to be sought out and embraced rather than shunned.

Like in the south of India, for example, I’ve noticed that people leave their slippers when they go inside the house. Growing up in my home, we used to leave English at the doorstep. And this was not a laid down rule. My father was a cardiologist, my mother retired as a librarian. They were both completely bilingual and it’s not like they didn’t know English and so they speak to us in English. No, not at all. But somehow, like people leave chappals at the doorstep, we would leave English at the doorstep and go in. And we spoke to each other in Hindustani, rather. And as a result, my Urdu is still a kind of a gharelu Urdu. I don’t have a critical idiom, even now, because I did read Urdu, still read it, access it and so on. But I do not possess a critical idiom because for me, Urdu is mostly a gharelu language, a language of everyday conversations.

As part of our effort to compensate our writers better, we at Purple Pencil Project have launched the #PayTheWriter initiative, where readers can directly show support and appreciation for our wonderful team.

Scan or upload this image on your UPI app, and show them the love 😀