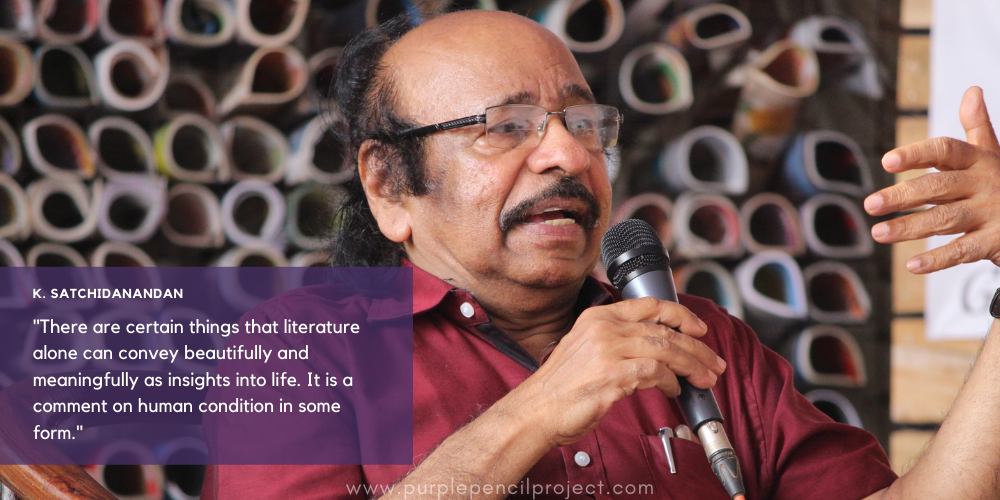

Celebrated bilingual poet, playwright, columnist, critic, translator and editor, K. Satchidanandan is among India’s foremost literateurs. The former Secretary of the Sahitya Akademi and Editor of the Akademi’s Indian Literature journal was the Poet Laureate of the 2019 Tata Literature Live Festival.

At the festival, he spoke to Purple Pencil Project about the Sahitya Akademi, how Indian Literature is viewed, his role as an Editor and more.

Excerpts:

What are the gaps that you see in the representation of Indian Literature?

K. Satchidanandan: There are two or three things we seem to miss very often. One is, there is a lot of tribal writing coming up. Dalit Literature has been mainstreamed at least in a few languages. It is not as marginalized as it used to be a decade ago. But when it comes to the tribal languages – writing in their own languages or writing in English, like in the North East, seems to be a missing element in many of the literary festivals. There is practically no representation of tribal writing.

Secondly, it is the North East itself. Unless they are given special representation, generally in the kind of average Indian imagination, the North East doesn’t even seem to figure.

Except for Assam and Manipur, the rest of the North East does not consider epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as their epics, they have their own folk epics. We need to specially take into account the North East and also the tribal languages and the new tribal literature that is coming up in those languages. And sometimes also in English as much of the tribal writing in the North East happens in English.

You have been such an integral part of the Sahitya Akademi. Do you think that it can play a bigger role in influencing readers and promoting Indian writers into the mainstream?

K. Satchidanandan: It has been playing its role since it’s very inception especially through translations and through journals like the English Journal called ‘Indian Literature’ and one Hindi Journal that is called ‘Samakaleen Bhartiya Sahitya’. Through these and also by organizing a lot of seminars, discussions and debates across the country, Sahitya Akademi has been playing it’s role.

What I did after I took it over in 1994 was mainly to open it up, open it to Dalit writers, more women writers and to the young writers as these were some ignored sections, including some tribal writers.

I started special platforms for them because otherwise they would continue to be marginalized. Like there were special platforms where only young people under 40 could present their works. There was another platform where only the marginalized like the Dalits and the Tribals could work. There was another special platform for women writers. That was how I could bring those neglected streams into the main stream. Because, until then the Sahitya Akademi was mainly an Akademi of sages who were wise and old people. But I wanted to change that picture and bring more and more young people and unrecognised writers into its fold.

Now it’s hard for the Akademi to go back because these writers are already very much present there. Many of these platforms still continue to function.

You were also the Editor of the Indian Literature Journal. What was that experience like?

K. Satchidanandan: Yes, for four years yes I was its Editor and that is where I learned all these tricks. It’s where I started all these platforms originally. I had sections, I had special issues on Dalit literature particularly Gujarati Dalit Literature, Marathi Literature. I brought out two special issues of contemporary women’s writing.

Later, when I became the Secretary, I got a chance also to organize All India Women Writers’ Conferences in Delhi and also in Hyderabad. Similarly, All India Dalit and Tribal Writers once in Jharkhand and once again in Delhi. Some of the things which I was not able to practice but only print in Indian Literature, I could now practice and print them on an actual platform. I think there was a relationship between my having been Editor and later becoming the Secretary.

How have you approached the digitization of literary works?

K. Satchidanandan: The digitization of literary works is something that is inevitable, something you can’t help. I belong to the old generation where I still love to hear the sound of the pages turning. But I think it’s only a part of the nostalgia of my generation. Maybe the next generation may not have that kind of a feeling. And now you know there are devices where you feel, like it is like paper, you feel like turning the pages and you get the overall feeling even though some of it maybe missing – like the smell of fresh paper and the joy of buying a new book. I still think the next generations will be very happy reading such things and for them it’ll be much easier than it is for us.

I also use various kinds of electronic gadgets for reading. It also has a very positive side in the sense that it can make works more popular. Especially if authors also co-operate and make their works copyright free or what they call ‘copyleft’ as I have done with some of my works. I hope that at least those authors who do not make a living out of their writing should let go of this obsession with royalties and be generous enough to allow everyone to have access to their work. My own plan about my works – I have done two works already, my selected poems and my play on Gandhi, they are available for free to download. And that’s what I plan to do gradually.

One problem I faced was, no publisher was then ready to reprint those books as those books were already digitally available. At the same time the digital availability was not sufficiently publicized and only a few people knew that it was available. So, there is a gap even now. Until India does not become a digital India as it is often said to be, there are quite a lot of people who are are left out completely, left out of literacy itself, forget digital kind of techniques. Hence, there is some distance we have to cover. But I am sure, with another generation or two, digital reading will become quite popular in India as elsewhere.

What are your thoughts on how literature is taught in the classrooms today?

K. Satchidanandan: I can’t generalize, unless people who really love literature, teach literature, there is a danger, that the students will start hating literature. I have a problem with teaching literature even when some of my own books are text books in Kerala. My poems have been in textbooks for at least 30 years now. But I am not very sure of how to approach this idea of a book or a poem becoming a text book because it becomes a kind of burden, you are compelled to learn it. Generally we derive pleasure from literature when we voluntarily read it, we choose to read it; not when somebody tells you that you have to read it and answer many questions from that particular book etc. Your reading is also constrained by that because you’re only trying to find the answers to the questions rather than enjoying the whole text.

But I believe there are good teachers who can perhaps bring these both together, the pleasure of reading and treating it as a text book. I am not sure that there are many teachers who really enjoy teaching literature – that is because they rarely enjoyed reading literature themselves. If you look at the students of literature, except for a few who have chosen the subject, many have accidentally come to literature, because they tried to get into IITs or IIMs or they wanted to do some kind of science, and finally when they did not get anything they thought to themselves – okay, if literature is my fate, I’ll go for literature or even philosophy. These are sometimes the last choices. And so their innate hatred of literature also unconsciously passes on to the coming generations. I am not saying that about everybody, there are people who voluntarily choose it.

Like I chose it. I had my degree in science and later I chose literature because I thought that was my real calling. Choosing the thesis for literature is very important because the teachers should teach the students to love literature and not treat it as a text book where you just have to answer questions and get marks for exams as a subject.

Is there a need to redefine literary values in this day and age?

K. Satchidanandan: Literary values have never remained the same anyway, because when life changes, literature changes, its form changes. At the same time there is also something common to literature because it gives you a certain insight into the human life which you don’t get from systematic philosophy or by studying Hegel or Foucalt or Derrida. One studies a lot of things and at the same time, one may not get the same kind of insight from Dostoevsky or Kafka or Tolstoy – essentially from the works of people who are called philosophers.

In that sense there are certain things that literature alone can convey beautifully and meaningfully as insights into life. Those values in some sense do not change. That basic value of literature as literature, that I think will remain even when forms change, structures change, styles change and topics change.

Often I’ve been asked to define poetry. I would only say that poetry is something that cannot be expressed in any other form. You can define it in the typical Indian negative term ‘neti’ – not this, not this. It is not a short story, it is not a drama, it is not a novel, it is not a movie, it can be expressed only as poetry and that is the only way in which poetry can be defined.

This is true to a great extent for literature also. It is very difficult to have a pre-defined idea of literature. But as I said, yes, it is a comment on human condition in some form.

You write plays, you write poems, you write so many genres and subjects. How do you keep them fresh?

K. Satchidanandan: It’s always a challenge. Even though I have been writing poetry for almost 50 years now, every poem to me is a new experience and I have to find the actual form for that particular experience. So, when I begin to write a poem I feel I am a beginner. Because I have to find the style, the metaphor, the image for that particular kind of experience. And that is what keeps my poetry or maybe the poetry of all genuine poets, fresh. That way, it becomes fresh by compulsion.

You are in front of a vacant paper and you have some experience in your head which is very complex and which is very hard to translate into language. You try to find the adequate language for that, the proper image, the apt metaphor, the real line, so there is this challenge. When you try to meet this challenge successfully, well, there is freshness there.

You are a prominent name in Malayalam Literature. What would you say it’s status is today?

K. Satchidanandan: Well I am not the one who should be really saying that but I believe that among the Indian Literatures, Malayalam is easily one of the most outstanding because it has a very lively avante garde; a lot of wonderful short story writers and poets from the younger generations. So I would compare it with a language like Marathi or Bengali. It is a very vibrant kind of literature and there is what is called as a literary culture, as writers are loved and respected and even the common people seem to take a lot of interest in literature, which does not happen in many languages.

If you take a language like Hindi, there is a community of readership but that is generally a community of elite people who study literature or teach literature but unlike that, in Kerala, even a coffee shop discussion can be around a book which has just come out or a story or a poem which has just appeared, so that makes a lot of difference.

Everybody reads because a 100% literacy rate prevails. I’ve had discussions with auto rickshaw drivers and employees in coffee houses about my latest poem. That’s what they call a literary culture. It has gone deep into the many layers of society.

2 Responses

Fuko= Foucault?

Dereda= Derrida?

Avangad- avant garde?

Too many errors for an article on literature! A good interview, but the interviewer doesn’t seem to have cared to check what words she didn’t know.

Thank you for bringing it to our notice!