Transcending linguistic borders, advocating social reforms and providing entertainment: here is what New India’s bookshelf looked like

Among the many memories of childhood, the most cherished are perhaps the stories we hear and read; in picture books, at bedtime with your grandparents, under the blanket with a flashlight, hidden between school textbooks.

Depending on how old you are, that first paragraph will bring to mind different stories – Enid Blyton, Harry Potter, Kalia the Crow and Shikari Shambhu – 90s kids from India will be familiar with these names. But what are the tales our grandparents read? The stories they dreamed about? The characters they idolized? The heroes they wanted to grow up to be?

Mythological tales, informative illustrated magazines, poetries, parables, novels that mirrored their social reality and stressed on historical importance formed the basis of our grandparents’ childhood. Here are some of them revisiting the tales they grew up with.

Art and life, life and art

78-year-old Narmada Joshi recalls with fervent pleasure that she and her sister were always found immersed in one book or another. Reading was popular back then because social reforms were taking place and novels captured this changing atmosphere remarkably well. “In my teenage and adult life, I read novels like ‘Gun Sundari’ (Virtuous Lady) and ‘Balika Vadhu’ (Child Bride). Navlikhas (novels) were usually relatable. It is why I used to love reading at the time. It was through reading that it dawned on me that there was so much more to life,” she reflects, as if watching her younger self pass her by in her mind’s eye. Authors like Gunawant Rai Acharya, Sarang Barot and others would write historical novels to keep the patriotic spirit alive among the newly liberated nationals.

“Literature back then was based on our social realities and the spirit of nationalism”, recalls 80-year-old Ratilal Joshi, retired as a mechanical engineer and professor at VJTI. “When I was 10, the fight for our Independence was still raging. To that end, pamphlets for kids and adults alike were circulated. They contained deshbhakti na geet ane nara (songs and slogans of patriotism). I used to peruse them a lot. For me, it became an impactful literary text of sorts,” continues Joshi, adding that this was also his initiation to the freedom struggle, small though it was.

72-year-old Kumud Joshi, grew up between Sunday outings to the chowpatty (beach) and novels her brothers brought her from the Parvatibai Hindu Library, which she read voraciously, a habit that ran in the family. “One of the most celebrated and prominent novelists of my time was Gulabdas Broker. He used to live in Malabar Hills and once we went to see his house. The board outside read, ‘This house belongs to author Gulabdas Broker’. I remember leaving a letter at his gate telling him about how much we loved his books. The genre of all these books was samajik (relating to social reality) and revolved around domestic relationships,” she remarks.

So many languages, so many stories

Malti Thakur, 75, grew up in Uttar Pradesh’s Bhavanpur and studied in a Hindi medium school. Most of her childhood was spent in playing outdoor games and learning to run the household. “I loved to read Rahim ke dohe and Kabir ke dohe (couplets), Kalidas’s Jeevni (biography). Kalidasji jis daal pe baithte the ussi ko kaant te the (He would do everything in a disorderly fashion and in an opposite manner from the rest of the world). In school, we studied poems on Gandhiji,” she shares.

Surprisingly, she remembers a couplet, and a few lines from the poem on Mahatma Gandhi, which you can hear in the voice note below. And she still reads! “I enjoy reading the Bhagvad Gita and Ramayana. I also subscribe to a monthly magazine called the ‘Arogyadham’ (Health Centre) which contains stories, chutkule (jokes), household remedies and parables, all in Hindi. It is my favourite.”

(The voice note can be translated as: Gandhiji is referred to as ‘Bapu’ lovingly. He is

the best in the whole world, he never loses hope and he is the light

of India.)

A retired Hindi and Marathi teacher, Tarulata Kalelkar, 81, loves reading more than anything else. She started reading because everyone in her family loved to read, including her older siblings. Having studied in the Marathi medium of Godrej’s Udyachal School, she read mostly in Marathi. Kalelkar is, to date, a bibliophile, with three cupboards full of novels, and even then has books lying on the window sill, on top of shelves and other cupboards. Probably making you wish she was your grandmother!

“English was a compulsory language till SSC and I remember learning small poems like ‘Twinkle twinkle little star’ in school. We also read poems like ‘Anandi Anand Gade’ (Joyfulness creates more Joy) and ‘Hirve Galiche’ (Green Gardens) by Balkavi,” a few lines of which she hums sweetly, to be heard in the voice notes below.

“Near where I lived there was a Marathi Granthsanghralaya (library) from where I would get books to read. I would finish a book in a day and even more during the holidays. Sometimes my brothers would buy the novels for me, even though they were expensive at the time. My favourite novel was Kusum Abhyankar’s ‘Aavahan’ (Warning). So was Rajendra Kher’s ‘Geetambari’, she said.

“One of the most popular authors back then was Pu La Deshpande. Many of his works were adapted into songs, TV serials and movies. Like his novel ‘Batatyachi Chawl’ was made into a daily soap and ‘Gulacha Ganapati’ became a movie. I went to see it when I was around seven or eight. I was also very partial to the genre of horror and used to love reading ghost stories like, ‘Kalikamurti’, ‘Veer Dhaval’, among many, many others,” she adds.

The larger structure of novels – length, price, were no different than as we know them. Novels were anywhere between 200-600 pages, had no pictures or illustrations in them whatsoever and were comparatively more expensive than magazines, which had a price range of seventy to seventy-five rupees.

A lot of magazines would emerge during Diwali with the theme of the festival of lights like, ‘Deepawali’ (Diwali), ‘Mouj’ (Fun and Enjoyment), ‘Deepak’, ‘Vasant’, ‘Deepali’, some of which are still available in print, she says.

Growing up in Karnataka’s North Kendra Kumtha, District Karwar, Hema Bhatia, 74, read in Kannada, Hindi and Marathi. “I studied in Kannada till 7th standard. The languages people conversed in back then were either Kannada, Konkani or English. We read poetries and story books in Kannada in school. I can ’t recall any names of the books, but I can still read Kannada if presented with it,” asserts Mrs. Bhatia, reviewing the life that had gone by.

’t recall any names of the books, but I can still read Kannada if presented with it,” asserts Mrs. Bhatia, reviewing the life that had gone by.

“I remember watching one of many Sivaji Ganesan’s films, in Kannada when I was young. His films were very popular back then. Kannada was a compulsory state language in Karnataka and my earliest memories are of reading poetry about Lingayats (Kings) of Karnataka and their history. The newspapers were also either in English or Kannada.”

“There were Marathi schools in my village back then because it was within the boundaries of Maharashtra, so I also grew up reading a lot of poetry in Marathi and Hindi in school; including those of Sant Ramdas. But when I was in 7th standard Karnataka and Maharashtra underwent a partition of their own, and my village became a part of Karnataka’s geographical territory. Consequently, all the Marathi schools shut down. But the libraries that retained Marathi and Hindi novels remained. From here, I borrowed story books written by Gyaneshwar and Nasi Phadke’s novels in Marathi. They were extremely gripping,” recollects Bhatia.

Multilingual seems to have been the theme of the days. “I grew up reading a lot of novels in English like, ‘The Scarlet Pimpernel’, ‘The Three Muskeeters’ and ‘Thelma’,” says Ratilal Joshi. “But my favourite was Charles Dickens’ ‘A Tale of Two Cities’. The detective stories of Earl Stanley Gardener were also very famous back then. The covers of books weren’t illustrated like you get now. They only had hard covers with the name of the book written on it and the books were usually bound”. He further disclosed that he had a friend, whose father had cupboards and cupboards full of Western novels in English and he would sometimes borrow books from him to read. From his collection, Joshi was introduced to the likes of Leo Tolstoy and George Bernard Shaw. In Hindi, he remembers reading renowned writer Maithili Sharan Gupta’s poem, ‘Panchvati’, and in Sanskrit, Jagannath Pandit’s poem, ‘Ganga Lahari’ (Ganga’s Waves).

Gujarat’s treasure trove

Narmada Joshi grew up in a Gujarati household and read most of her novels in Gujurati. “Ramanlal Vasantlal Desai was a legendary author in the Gujarati community,” she recollects. “The earliest memories I have of my childhood are of reading countless, random Bengali stories in Gujarati, names of which I don’t remember. Kanhaiya Lal Munshi’s ‘Patan Ni Prabhuta’ (Pride of Patan) was very famous. I also read his ‘Jai Somnath’ (Hail Somnath).”

“Gowardhanram Tripathi’s writing style was exquisite. I read his works in Gujurati which usually had family oriented themes in them with a Maharashtrian background. I read his ‘Saraswatichandra’ thrice,” reminisces Ratilal. “There were a lot of book stalls in Fort- at King Circle, Fountain, Bori Bunder Road, near Metro which would sell and lend, both educational books and novels at the rate of two to five rupees per book. I think some of them are still there. We were required to return a book within a week and it is from here I got most of my novels to read,” he says, eyes aglow with reverent nostalgia.

“My mother’s name was Kashibai but everyone used to call her Kashi Kavi because she would read a lot in Sanskrit back in her day. Reading was a big deal then,” recalls Kumud Joshi.

“For as long as I can remember, everyone in my family was a big fan of reading. My siblings would love to read the newspapers so much so that the neighbours would say they’d never heard my siblings speak and didn’t know what they sounded like! All they ever did was read. They would often comment that it seemed like we were running a library in our house,” she laughs, nostalgically.

“My father’s office was right opposite the Library in Masjid Bunder. The price of a book was usually determined by the number of its pages. But if one wanted to borrow books, one simply had to get oneself registered in the Library and pay a hundred rupees. The rate was then decided according to the time span within which one returned the book- a week, a month, a day. There was a bespectacled aspiring poet in the Library who would recite his poems to anyone who would listen. Soon, he had an ardent fan following and went on to become an acclaimed writer. His name was Ramesh Desai. But my favourite author was Vaju Kotak. There is even a Vaju Kotak Marg in Fort to this day. Magazines ‘Chitralekha’ and ‘Jee’, novels ‘Chundri Ane Chokha’ (Dupatta and Rice) and ‘Ramakda Vau’ (Toy-like daughter-in-law), were some of the many, many works of his that I read. Chundri Ane Chokha was very famous and was adapted into a Gujurati movie. His book ‘Ha ke Na’ (Yes or No) had four parts, but he died before he could finish the last one. His wife completed the series for him and then published it. Gowardhanram Tripathi’s ‘Saraswatichandra’ was a famous movie that was made from a book of the same name. The book had two characters named Kusum and Kumud Sundari, who were sisters. My twin sister’s name was also Kusum. My mother-in-law would often jokingly summon me as Kumud Sundari.”

She further adds that she read a lot of Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry in Gujurati and studied about Subhash Chandra Bose in school. She also read a variety of popular comic books like ‘Bakor Patel’ which had the face of a bakri (goat) on the cover and ‘Chako ane Mako’ (Chako and Mako) which contained stories about mischievous children and their many antics. It was written by children’s author Jivram Joshi. According to her memory, it was for fourteen and under. “I read newspapers like ‘Janmabhoomi’ and ‘Mumbai Samachar’. There was also a weekly children’s newspaper called ‘Jhagmag’ (Sparkling) which printed mythological stories, general knowledge facts, etc. I also read this magazine, very popular for its name, called ‘Chakram’ (Crazy) by N.J. Golibar. It was very happening back then. Golibar Publications is still up and running in Ahmedabad and is run by his kids. It was fifteen to twenty pages long and contained parables, pictures of birds with names and puzzles, etc. Its name was later on changed to ‘Chandan’ because people made fun of it a lot,” chuckles Kumud Joshi. She still reads, she says with pride. She has completed every book in the local library in her vicinity and they now refuse to lend her books! Once a bibliophile, always a bibliophile!

Translations for the win

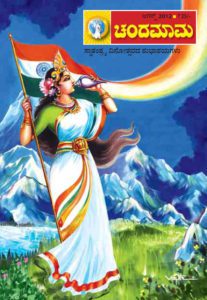

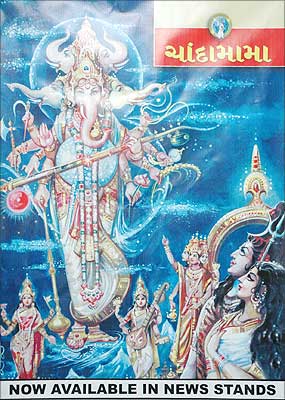

“I read magazines like ‘Chanda Mama’ (Moon Uncle). ‘Chanda Mama’ was published in almost every language”, recalls Kumud Joshi.

“Chandoba was my favourite. It had jokes, fables, stories of raja rani (kings and queens) and stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The illustrations were great and I used to enjoy reading this magazine very much,” says Tarulata Kalelkar, with a certain fondness. Almost everyone interviewed had read the magazine in their own language, a testament to its widespread popularity.

Translations helped immensely, and through, some common literary giants emerged.

Hema Bhatia also shares the story of how she maintained contact with Hindi as a language. “In Hindi, I read a lot of translated works of authors like Sharad Babu and Rabindranath Tagore from Bengali. Not a lot of Hindi magazines were available back then in Karnataka, so novels and other prose was all I read. Relatives of mine would insist on us studying Hindi as a language, as they stressed on the fact that we should be well versed in our national language, and it’s how I kept in touch with Hindi over the years. Be it any language, I used to enjoy reading short stories and novels the most.”

Translations enabled individuals to experience the rich language and stories of other communities. Where linguistic limitations only cloak the charm of any literary piece; during this uncertain and eventful time, they served as a beacon of unity and oneness.

Below are approximate summaries of some of the works mentioned:

Gowardhanram Tripathi’s ‘Saraswatichandra’ (Gujurati)

This critically acclaimed novel written in four parts, revolves around a young lawyer named Saraswatichandra with an idealistic mindset and a profound interest in literature who renounces his household and begins his pilgrimage. Consequently, his fiancé Kumud Sundari is married off to the wayward son of Buddhidhan. The latter happens to meet the erstwhile lawyer on his pilgrimage. Impressed with him, he invites Saraswatichandra to stay in his home. Fate brings Kumud Sundari and Saraswatichandra under the same roof once again and the story continues from there.

Chanda Mama (magazine) (all languages)

A monthly children’s magazine, Chanda Mama was published in over 12 Indian languages and English. It contained mythological stories, parables and jokes, all accompanied with interesting illustrations.

Rajendra Kher’s ‘Geetambari’ (Marathi)

This renowned novel belonging to the philosophy genre is based on the Bhagwad Gita. It includes a background on the Mahabharata, many references to it and the dialogue between Lord Krishna and Arjun.

Maithili Sharan Gupta’s poem, ‘Panchvati’ (Hindi)

This famous poem describes the home of Lord Rama, Laxman and Sita during the last year of their 14 year exile, a cottage in the forest of Panchvati. Laxman is guarding the cottage as Ram and Sita sleep inside. The poem also goes on to describe the cutting of ears and nose of Ravana’s sister Shurpanakha, by Laxman.

Jagannath Pandit’s poem, ‘Ganga Lahari’ (Sanskrit)

This poem has one 197 shloks (stanzas) wherein Pandit Jagannath and Kanika (daughter of Emperor Akbar) sit on the banks of river Ganga, and sing to her with devotion to carry them away. They had gotten married against all customs and were ridiculed and made to suffer for the same. They sing with such purity that with each shlok, the water of Ganga rises up towards the doomed couple. The poem ends with Ganga carrying them away to the shock of those who were against this marriage.

**The translations of the titles are crude, as not all were available online. If they need to be changed, please write to us and we will make the corrections.

***Feature Image Credits: Malvika Asher/Google Arts & Culture

2 Responses

Great going Jessica. I m not into reading, but this may def inspire me to start one. May god bless u with grt success in what ur doing. Keep Going. ???❤

Thank you so much! ? So glad to hear you’d like to start reading ❤️