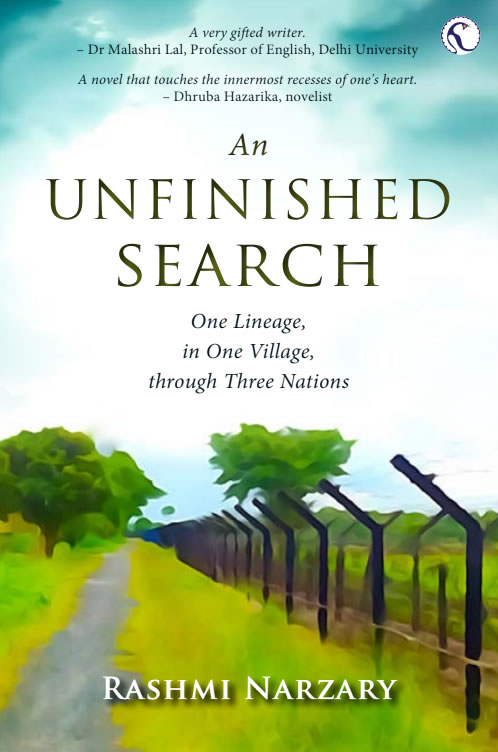

Team P3 is in conversation with author Rashmi Narzary where we talk about her latest book An Unfinished Search (Published by Pippa Rann Books)

Rashmi Narzary is a dog-lover at heart, an author by passion, a creative writing mentor, and an independent editor.

Her book His Share Of Sky was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Prize for Children’s Literature in 2016. Bloodstone: Legend of the Last Engraving was her debut novel.

Some of her work is taught in undergraduate courses, and some is being translated into Vietnamese by the Japan Foundation. Rashmi Narzary lives in Guwahati, India, with her husband, two children, and a happy host of pets.

Team P3 recently spoke to her about her latest book An Unfinished Search.

In Conversation with Rashmi Narzary

Team P3: Every book begins with a germ of an idea. What was it that led you to research and write An Unfinished Search?

Rashmi Narzary: Without a second thought and moment, it was the graves bearing no headstones at the Malegarh War Memorial, in the Indo-Bangladesh International border at Assam’s Karimganj District.

Though these graves do have grave slabs, unlike in many other War Memorial Graves, these slabs have nothing written or marked on them to tell who lies peacefully underneath, or where they came from. And in a mind that seeks to know and is fond of stories, many questions began to emerge. So obviously, a kind of imagination started taking shape, an imagination that attempted to answer the many questions that arose in my mind.

Standing on that quiet ground, staring at the graves, this thought slowly crawled up my spine, you know, that, is the soul of the physical land even bothered by which country it is placed in? However, people are. They have unsettled, made refugees, and even killed and martyred for land that budged not a hair’s breadth, yet moved on to be placed under different rulers.

Back along the dusty border road, the high, winding, barbed fences punctuated by massive gates of sheet iron that facilitated visa-less movement for villagers with homes in Bangladesh and paddy fields in India, riveting anecdotes from the BSF Officers at the Sutarkandi Out Post and above all, the heart-wrenching stories that the locals narrated, all of these at times pleaded and at other times bullied me into researching and penning An Unfinished Search!

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Team P3: The story, although situated in one village, flows between three countries – India, East Pakistan, and Bangladesh – as the tide of history takes it to the borders of two countries and later a third.

Your note in the book mentions that the soldiers at the memorial at Malegarh are not recorded in the British army papers. Did that fact serve to build up the narrative of a family whose origin is lost with the unknown buried soldiers?

Rashmi Narzary: That the soldiers at the War Memorial at Malegarh are not recorded in the British Army papers served not to build up but to give direction to the narrative. The fact reinforced and described with greater clarity, intrigue, and effect, a narrative that was already building up.

Had the British army papers recorded otherwise, well, even then, the Hazratkandis may never have got to know of it, search as they might…for my narrative was already building up along lines that didn’t get them to find their identity. But yeah, the fact did give a realistic bend to the narrative.

I quote from the notes in the epilogue section of the book,

‘Records of the rebelling 34th. Regiment Bengal Native Infantry (34BNI) and names of sepoys therein, were removed from the official records soon after the mutiny of Latu. That is regretful standard military practice since time immemorial. So what is available today is primarily the names of the British officers, though there are also the names of a few ‘faithful’ Indian Subedars, etc.’

Enjoyed reading this interview? We recommend you to read Anurag Anand: A Brilliant Artist and Amazing Writer shares his journey.

Team P3: The events in this one family’s lives reflect world events of 1857 and later of Partition. Having a family and its story in close focus as a telling indication of the bigger events happening around them is a great narrative device.

Did these two scenarios – the family and the larger more expansive one – grow organically as the story progressed or did it require quite a bit of plotting?

Rashmi Narzary: Organically ofcourse.

When I begin to tell tales, I have noticed that the organic, spontaneous growth of the tale and the meticulous plotting do not remain in well-demarcated chambers of my imagination. They spill out into one another and before I realize it, there occurs a seamless weaving of the two. Like in earlier works, at times I take a mental stroll through my plot where I often come across characters, situations, events, landscapes, and emotions that I hadn’t plotted but which, I realize, form an integral part of the narrative and so add these to the description.

Thus, the organic and the meticulous plotting meet. I sure did a little bit of plotting here too, but as I begin to narrate, if the narration meanders a little from the plot for a better, more engaging storyline, then I let it. It’s almost incredible, you know, how the mind just does an extempore! So there’s a bit of both – plotting and organic growth, with the latter winning hands down.

Team P3: The society in Bengal at the time is very evocatively portrayed with the easy camaraderie of friends of different faiths living quotidian lives. Until events overtake them. Yet Asman retains his mental and emotional balance. How could the violence and mayhem all around not affect him?

Rashmi Narzary: Oh, it does affect him for sure! …When Asman was a little boy in school and was one day walking to the graves with his grandfather Anjaan, if you recollect, he was telling his grandfather that Sudipto Kar was leaving school and Hazratkandi, and how sad it made him, because ‘they belonged to a faith different from most in Pakistan, they may not be allowed to live in peace…..’ Later on, after the massacre in the Hindu villages, ‘…Asman’s soul cringed…’

And finally, after the brutal murder of his parents, ‘…he would let no more Hazratkandis ever be…’ and ‘…had lost the will to build the house over again…’ and let it be with the tell-tale charred marks of that fateful night. These are all reflections of Asman’s mental and emotional imbalance through different ages of his life.

Team P3: The river Dooni is a strong presence throughout, almost a refuge for the characters when they need space to mull over ideas and events. The Gulmohar tree outside the cycle workshop is almost a character in itself.

Eastern India is very well known for its scenic beauty. Was it a conscious decision to have nature play a prominent role in the narrative? Please expand on how nature helped make the story more evocative.

Rashmi Narzary: Nature is, actually, an integral part of the person I am. Having had a childhood in Shillong, Meghalaya, and living all my life very close to nature, I find that every hill, tree, river, and cloud has its own beautiful tales to tell. In the northeast of India, we see nature as one that nurtures us, our deity, our ancestor, and our successor. We are, because of nature. So perhaps nature’s role in the narrative was only expected, and not a conscious decision. However, certain events related to them were conscious.

For instance, Firdaus’s head being banged on the Gulmohar’s trunk, a young, runaway Anjaan drinking from the Dooni even as he remembers his abba telling him that the water in it was only for cattle, the leaves that fell from the Gulmohar onto the bench to keep Ijaaz Miya company, and the flinging of the bench into the fire. I could see nothing but a piece of nature as the caring, maternal tree trunk (again!) onto which the narrative hugs for nourishment, like the exotic orchids back here, to come to life.

For me, nature helps bring a tenderness to the tales I like to tell, leaving a kind of lingering emotion. In this narrative, even the bench under the Gulmohar, for that matter. Yes, the Dooni, the Gulmohar, the bench, they all are almost characters like you so rightly say, just as is the bird’s nest on the bokul tree near the graves.

Team P3: Please expand on your women characters in the book. The two main ones, Laila and Firdous, appear to inject a dose of common sense into the proceedings as the men take up the quest for a family name throughout their lives. Firdaus offers perspective when she says that all names have to begin somewhere and will grow into the family name over generations. So why all this angst?

Rashmi Narzary: Okay, now here is something consciously portrayed, Laila and Firdaus. It is not usual for women in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh subsequently, of the times of the narrative, to be fearless, outspoken, be listened to, and have their men folk share pertinent discussions with them. But I groomed Laila and Firdaus to be just these.

Even Najma, with her small stature, was ‘…big in her confidence…’. Despite the prevailing social strata and the personal circumstances they were in, they yet were the only strong elements in the narrative. The male protagonists were emotionally bruised, humiliated, and resigned to a hopeless search. Hence the women characters were sketched as the strength to lean on and come home to.

Coming to Firdaus saying, ‘…all names begin somewhere…’ The angst here lies in the fact that for their name to become a lineage, they will have to look ahead, into the future. But what the Hazratkandi men are looking for is not generations succeeding them into the future but generations, or at least one, preceding Anjaan Hazratkandi, in the past. They are eager not to establish, but to inherit. And be known as someone, belonging somewhere.

Team P3: The idea of generations of a family being focused on one issue, in this case, that of identity, in an unbroken thread is not an easy narrative to keep together and bring to fruition on the page. What was the impetus, the one moment that gave you the idea that identity could be the focal point for An Unfinished Search?

Rashmi Narzary: Thanks for the appreciation.

Yeah, the same again; unnamed graves on a land that has been juggled by the politics of nations as if it were a toy. On one hand, we didn’t know who the unsung martyrs were, and on the other, the ground in which they lay buried too, has not had a stable identity.

So at that moment when I stood there in the solitude of the Malegarh War Memorial and the breeze gently caressed me from all sides whispering about lost identities of both the land and the buried martyrs, I felt, ‘yeah, here is a story sitting to be told, a story with identity as the focal point.’

Team P3: As a South Indian, I have to admit I could not identify with the ribbing Asman and Baadal take for having the name of a village as their surname. It’s quite a common practice in South India for a person’s name to be in the sequence of his village name and then his own name.

But I understand that it could be an issue in Eastern India where that is not a prevalent method of naming people. For Asman is the issue double-edged, since the lack of a surname not only clouds his family origins but also his religion – important markers for society there?

Rashmi Narzary: Yes, many have asked me about this. The concern here is that the three Hazratkandis do not know if they even belonged to the village named Hazratkandi, and it is precisely this that sketches the storyline. As you say, for many a community elsewhere, it is common practice to have the name of ‘their’ village as ‘their’ surname.

Because ‘they’ belong to it, and ‘they’ know it for sure. Which is not so for the Hazratkandis. For after his return from Dhaka, Anjaan tells Asman, ‘…the Subedar…looked at the map he was reading and asked me if the Hazratkandi in my name was the same as the village on it….But that too would be alright, Asman, had I known that I belonged to it…’ (Pg 264-265) .

Oh yes, it is indeed a double-edged issue for Asman- the lack of a surname and not knowing what faith he belonged to. You’ve so accurately interpreted that! There is as much tolerance and understanding towards the faiths of others in the northeast of India, as there is a strong kinship and bonding amongst their own. Which makes it all the more fundamental to know to what faith one belongs to. However, the lack of a surname and family origin is not to be seen as northeast-centric.

As Malashri Lal says,

‘…this is everyone’s timeless story…. There is an eternal quest for attachment— for someone, someplace.’ Signifying markers for society almost everywhere.

As part of our effort to compensate our writers better, we at Purple Pencil Project have launched the #PayTheWriter initiative, where readers can directly show support and appreciation for our wonderful team.

Scan or upload this image on your UPI app, and show them the love!