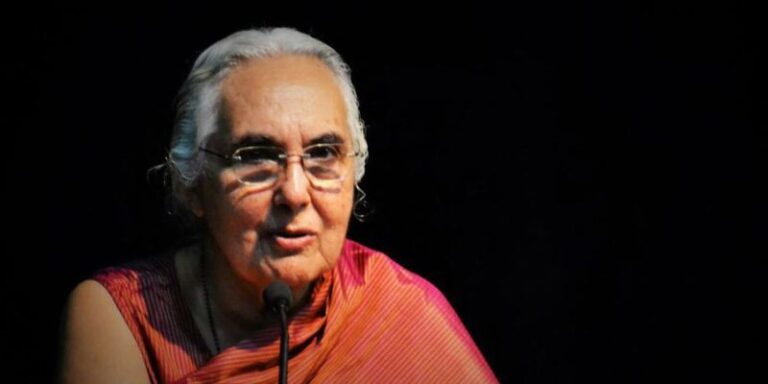

Amritesh Mukherjee from Team P3 was in conversation with Nilanjana Roy at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2024.

Nilanjana Roy‘s love for books is evident in everything she says and writes. She’s written two delightful fantasy novels, The Wildings and The Hundred Names of Darkness, and a noir fiction set in Delhi, Black River. She’s also written a collection of essays on her love of reading, The Girl Who Ate Books, and edited several anthologies.

Amritesh Mukherjee: What inspired your latest book, Black River, and how it reflects your personal experiences?

Nilanjana Roy: Part of the book came out of living in Delhi for many years, loving the city, but also starting to see it through the eyes of people who came from very different worlds than I did. You start to wonder what the city is like for migrants who come here from Bengal, Bihar, and other parts of UP, and what kind of friendships they make.

One strand was very sad. It was just to do with my years as a gender reporter for The New York Times, and feeling that I was looking at a landscape of absence where many girls and young women are killed casually. We move on. The new cycle keeps moving on. But you don’t see the dimension and the depths of that loss in the lives of the people left behind. Of the father who might grieve his child. Of the family who might spend the rest of their lives with these absences.

We move on. The news cycle keeps moving on. But you don’t see the dimension and the depths of that loss in the lives of the people left behind.

Nilanjana Roy

The third strand was when I was writing this story, around 2017-18, and you could feel the temperature of the country changing. We have learned to live alongside each other after a great deal of pain, to put aside our differences, and to come together as Indians. In part through the freedom struggle, in part with the partition, we came back from that terrible period in time of massacres, that deep rift. Now you feel those old bonds being forcibly severed and ripped apart.

I wanted to capture a little bit of the friendship that can happen when you come out of places, where you’re not even allowed to meet, into a place like Delhi where willy-nilly a Chand and a Rabia and a Khadir might find themselves slummed down on the banks of the Yamuna. Out of that, an unexpected but lifelong friendship springs up. So, it is about friendship as well as much about murder.

Amritesh Mukherjee: You have dabbled between different genres: fiction, nonfiction, fantasy. How does your writing process differ for each of them?

Nilanjana Roy: It’s organic. I’ve been very, very lucky to spend my life as a reader, sometimes an editor, and a writer. I love books, I love reading, and I love the fact that instead of this short attention span, you get an entire world in which you can immerse yourself, you can escape into it, or it can simply wake you up as well. I edited about three different registers. I’ve held many jobs before I was a writer. My first two books were fantasies about a clan of cats set in Delhi, where the street dogs jumped in, the geese jumped in, and the tiger also made an appearance. But I think I like switching gears a lot.

Partly, it’s the book you want to write that shows you what its form is going to be. Writing shouldn’t be that serious either; it should be a little bit of a playground. You should feel free to jump around and do what you want. When you change genres, you also change your muscles and learn, or you have to learn a little bit more. Whether you’ve learned that or not, it shows up in the book.

It’s part of what makes writing fun. You’re not doing the same thing over and over again. As each book changes, it also shapes you. You start to understand what it is you so keenly want to write about. For me, the entire writing career could be summed up as humans are interesting, and non-humans are even more interesting. So I want to do as much as I can in as many different forms as I can.

Amritesh Mukherjee: What is your next project? What genre will it be?

Nilanjana Roy: I’ve almost finished a couple of drafts. This one is easy because I’m staying with crime for the next book and bringing back just one character from Black River. I’m staying with crime because I still have something to learn from this, in terms of tempo and beat. Black River almost had a slow melancholy about it. It’s a book that’s very fast-paced at one level but also has a slowness to it.

The next book is going to be very different. It is set in Delhi but also partly in the Himalayas. I’m going to have as much fun as I possibly can.

Amritesh Mukherjee: Your initial books have a deep-rooted love for wildlife. How is your passion for raising awareness about nature reflected in your work?

Nilanjana Roy: I don’t think I consciously wanted to raise awareness, but the cats changed things for me. I didn’t grow up with pets. One of my family members has a serious case of asthma. It was only after I got married that we adopted our first cat. It was very small, and a little ginger, very bright pink. Her name was Mara, the same name as Mara in The Wildings. She had a loving heart. Then she went off because she was a friendly little soul. She introduced us to other cats. At some point, I realized I was living in a city: Delhi, Kolkata, or Bombay.

But these aren’t just human cities. They are in the middle of nature. Nature does not live at a distance. The cats also love me to form friendships (with me), and currently, I’ve made a slightly unwise friendship with a cheel who lives on the roof, and her grip’s very strong. When you follow animals around for any length of time, you understand that their lives, friendships, sorrows, and griefs are as strong and as important to them as they are to us. We see monkeys as a nuisance, slightly dangerous and scary. They’re constantly being chased around the city, which is as much theirs as ours.

Amritesh Mukherjee: I’ve always wanted to have a monkey as a pet.

Nilanjana Roy: They open the fridge and raid bananas, they do that a lot. And they’re very clever at opening locks and things, so be careful. But they’re protected species, so you can’t have them as pets.

Because I like walking around the city a lot, after a while, you see that it’s not the humans here or nature over there. We all need to come out of our phones a little bit and look around us. If the air is polluted in Delhi, why is it polluted?

When our earth is damaged, and the places around us are damaged, when there’s dust in the air, and the rivers are choked, you feel it in your skin, whether or not you care about it.

Nilanjana Roy

Why have we let things get to this point? When our earth is damaged, when the places around us are damaged, when there’s dust in the air, and the rivers are choked, you feel it in your skin, whether or not you care about it. And you feel that because we are not apart, this is not separate. Nature is not just pretty scenic backgrounds. It has a wild, elemental force that demands our respect.

Amritesh Mukherjee: You have changed many roles throughout your career: editor, journalist, author, researcher. How have these roles shaped the way you think?

Nilanjana Roy: Researching and editing has helped. I lean a little towards journalism at this point because it’s familiar, and there’s a security to it. What these roles teach you is research. You learn how to go to archives. You learn how to look up things, seek interviews, and check facts. That’s the mechanical stuff. The big gift journalism gave was the ability to stop and listen and interview people who came from very different circumstances and backgrounds than yours.

Very early on as a journalist, the big thing that you learn is that your perspective is not the only thing. The way you see the world and your comfortable certainties are not shared by everybody. You get used to not just listening but trying to figure out if this person has said something, and I find it hateful, or biased, or bigoted, or whatever. Where does that come from? What has formed his worldview? You try not to judge so much and try to understand a little bit more, even when you fail.

The other part of writing is also just the imagination. That’s something that I’m stepping deeper and deeper into. The imagination is incredible. It’s hard to describe. If you ask writers where the ideas come from, they have all kinds of cute responses, but the truth is we don’t really know these people who make it into our books. While the Wildings is pegged as fantasy, the large part of it was realism, simply because I knew the animals I was describing. Mara is a cinder. She has long whiskers, and she picks up on visions. So it’s okay. It is magical realism.

Amritesh Mukherjee: You have been a part of the literary community for a while and have seen it change over the years. There’s the added element of how social media has a pervasive presence in our lives. I remember reading somewhere that when two people meet today, it is not two people meeting, but they are two algorithms meeting. And it’s very simple, if you are a young kid and you have never opened YouTube and you receive any link from someone.

You open it, and that shapes your algorithm and how your digital career will be. How do you see the influence of this media changing society and literature? Recently, we interviewed Anjum Hasan, and she talked about how literature is changing. It’s becoming more rapid. A good part of the literature you see is more centralized on capturing attention at every point. It doesn’t ask the reader to put too much effort into what they do. What are your thoughts on the same?

Nilanjana Roy: I see social media in two ways. One is benevolent: old Twitter, and, particularly back in the day, Instagram. It’s a great tool for discovery. It’s a great tool for you to find your community. It can bring you out of loneliness. The flip side of it is that when your life becomes all about sharing something that’s a little unreal and about seeking likes, that’s the problem. Everyone is running around in search of attention. Attention must become a currency that’s very valuable and important. In all of this, what about yourself? What about the quieter part of yourself? It’s all so noisy and demanding and must be terrifying.

The story that wins is the one that most efficiently abducts your emotions.

Nilanjana Roy

My twenties, my teens, and twenties were free of this pressure. I cannot even begin to imagine how difficult it would be for anyone growing up now to try to balance all of that. I don’t have pronouncements here, but I would say a few things. Try to spend a fair amount of time offline as a reminder to be anchored in another kind of world. I won’t say real or unreal because the people on social media are very real.

What it does in terms of storytelling is downright dangerous. The story that wins is the one that most efficiently abducts your emotions. Automatically, stories that prey on fear, on your fear of the other, on anger, on deep grief, those stories come to the fore. But quieter stories or more complex stories, something that says that history is not as simple as you think are sidelined because those require time and reflection. They almost never win, and we are losing a lot of them.

Recommended Reads: Black River Review: A Deadly combination of murder and mayhem

How does it change writing? In two ways. For a lot of writers, we are not this forward-facing. You have to learn to do something; for example, sharing my sessions at a festival is new to me, but then I decided I was not going to do it to get readership. I would try to do this for sharing something or preserving something for my own pleasure with friends. There has to be something real behind it. I don’t think I’m very good at being a brand. I think I would be a very bad brand.

Amritesh Mukherjee: It is rather obnoxious, this necessity for everyone to have a brand.

Nilanjana Roy: Not every author wants to do this or can do this. We’re seeing that it’s the artificiality that brand-building promotes, which is dangerous and can suck you in. The novel in recent years, whether it’s been Indian fiction, when you look at what Devika Rege or Tejaswini Apte-Rahm or Janice Pariat, to name three of the recent writers, are doing, you see that there is a deep pleasure to making something, creating something, to staying with writing for a period of months, sometimes years. What is it about that that we love?

It’s hard to take your book through several drafts. And yet, most of us don’t speak of the hardness, but we speak of the wonders of discovering a story. There is a huge benefit to not just slowing down, but doing deep work and reading novels for pleasure. Some of the deepest pleasures come from switching off social media and disappearing into this world that feels perfect because it’s been built layer by layer, bit by bit over time.

One of the areas where storytelling is inexorably going to change is with the advent of AI. But I’ve seen so many things come and go that I’m also looking at this with a little bit of skepticism. AI will change the world, yeah? We have got this before. It’s gonna make it much easier to produce novels as a commodity, as a product, as something that can be placed on the shelf.

But have you ever played around with AI? Prompt creation is an art. And depending on the prompt, everything changes. Do you really want to ride that dragon? In that case, you have to learn how to train it. Don’t forget AI, at its best, what is it trained on? The human voice. Human books, including one of mine that was logged into a data set, along with half the world’s writers. Ultimately, AI is not that artificial.

For me, the entire writing career could be summed up as humans are interesting, and non-humans are even more interesting.

Nilanjana Roy

There is a part of it that is very human and very messed up. The pleasure of any form of art, we’re talking about novels, fiction, writing, at this point… The pleasure of anything you see, a music performance, or spending time with art- I don’t mean just walking through an exhibition, but just sitting there and letting a painting or a sculpture change you.

I’ve seen that happen so many times, this time at JLF. People stop by those huge metal horses or that wall with the demons and the Asuras being painted. They pause; they want to take something in because it enriches and nourishes them. I do not think that literature will lost that. For a brief while, you might be writing to hook attention, but honestly, writing is the worst way to do that.

Instagram is better, and reels are better. If you want attention, you can find it in different ways.

What is writing about? It’s about depth. It’s about returning to yourself. It’s about discovering things that you never even knew existed. All you have is 26 alphabets and every one of you can create a completely different universe out of them, and that is magical.

Amritesh Mukherjee: I read a few months back how reading is the only active form of entertainment. All other things, whether listening to a song, a podcast, or watching a film, are passive. You do not have to put in any effort. It’s just being fed to you. While I’m not demeaning any of it, reading is the only form of entertainment that requires you to constantly pay attention because the moment you stop doing that, it stops. What are your thoughts on this?

Nilanjana Roy: I agree and disagree. I see exactly what you mean about reading being something that challenges you because, with the words, you’re taking that and re-creating a character. Something that’s been said for a very long time that a book is partly created by the writer, but it’s also partly created by the reader. They are co-owners, co-authors.

Two people can read the Wildings and come up with completely different impressions; how they see Mara or Katara, would be different for each of them. I don’t know. I can’t look inside your head. But not everything is there to just be just consumed. I was sitting out on the lawns with a keen music aficionado, who was definitely not just consuming a concert but listening with care and intention and with that massive vocabulary of music behind them.

Very early on as a journalist, the big thing that you learn is that your perspective is not the only thing.

Nilanjana Roy

It keeps coming back to the reader. It keeps coming back to the person who is being fed, whatever it is on social media. Do you want to be a consumer? Because then your life goes in a different direction. Or do you want to be active in literature from the world? It may be a fictional world or an imaginary world. What is it that you want to let into your life? What is it that you want to bring in? You can also stop the habit of mindless consumption of always wanting to be entertained. Wanting to be entertained is absolutely fine. Totally. But wanting everything to be made easy. That’s not what life is about.

Amritesh Mukherjee: The analogy of Huxley’s A Brave New World comes to mind. What were some of your literary influences when you were growing up?

Nilanjana Roy: I love the way you frame the question. When people ask me what my favorite book is, my mind goes blank because there are too many and too many from different periods. But I grew up in a very eclectic, book-loving household. My father was from Orissa, but he knew Bengali. My mother is Bengali. We grew up assuming that both languages belong to us. Later, you encountered questions about English. I read everything. I was a pest. I used to bother people for stories all the time.

What I remember most is, surprisingly, poetry, whether it was Abol Tabol or whether it was, uh, A Child’s Garden of Verses, edited by the adventure writer Robert Louis Stevenson, an old anthology. I remember folktales very powerfully like Tuntunir Boi. In Bangla, a lot of it is very rhythmic, and as a child, you’ll love that beat. But we also grew up with a lot of Russian children’s literature. And Olga Perovskaya’s Kids and Cubs. I mentioned this in interview after interview about Wildings.

Very few reporters take down that name because it’s unfamiliar to them. You know, they take down the others because they remember that. Richard Adams’ Watership Down, people know it is a book about rabbits. But she was this Russian writer who wrote the most marvelous stories about growing up with a family that took in foxes and befriended tigers because they lived in the wilds of Russia.

The imagination is incredible. It’s hard to describe.

Nilanjana Roy

I’d only discovered many years later that she had been jailed on one of Russia’s more repressive purges and spent many years in the labour camp. But these stories were full of sunlight and happiness, and they made a positive impression on my mind. As an older reader, I loved Garcia Marquez, I loved Rushdie, and I love Tori Morrison with all my heart. In Hindi also, there was Champak. It was a little magazine story.

Amritesh Mukherjee: My dad was in the army. So when we would travel, he would always purchase a Champak, and there would be these Prem Comics.

Nilanjana Roy: Yes! There was Champak, Tinkle Comics, and Shankar’s Weekly, and if you remember, those were big influences, because they made Indian Engilsh more comfortable before, even Shobha De and others. That’s where it came from. There used to be these huge books that a benevolent friend in America sent us, Illustrated Folktales from Around the World, and I was in love with that book.

This friend also sent us beautiful editions of Winnie the Pooh, Charlotte’s Web, and Stuart Little. I didn’t like my Hindi teacher at school. Hindi, I only discovered in my 20s. I started to read the stories of Shivani Ji and Agyeya. Then I was like, this language is beautiful, and there are so many forms to it. There’s no one Hindi, but there are multiple Hindi. It’s like rivers flowing into an ocean, and I never stopped reading.

It’s crazy how the world is going upside down. We have autocracies developing, social media, and wars breaking out in the Middle East and Europe. But in terms of books, I am amazed at how writers always step up to their time.

Nilanjana Roy

I’m looking back, and you’re making me think about this. I have always known that I was lucky to grow up in a house where people prized books the way today people prized success. Others would say, ” Oh, my father has this car,” but we would be like we have books, and our father buys encyclopedias, and mother tells me stories; that was wealth. I thought I was lucky about that, but you’re making me realize that I was also very lucky to have not one but three languages. It’s been such a wonderful lifetime of reading.

Amritesh Mukherjee: What are you reading right now?

Nilanjana Roy: I’m starting to read a lot of Indian writers who are doing nonfiction and fiction. Perumal Murugan’s beautiful set of short stories. I knew his novels well. I opened his short stories, and it starts with a lovely story about a cat where the cat is not very cute or small. But the cat is given respect, dignity and treated as a cat, and I was completely sold. It’s called Sandalwood Soap and Other Stories. I’m reading a couple of manuscripts by friends that I’m really excited about, some novels coming out next year. I’ve been reading a lot for reviewing purposes.

It’s crazy how the world is going upside down. We have autocracies developing, social media, and wars breaking out grievously in the Middle East and Europe. But in terms of books, I am amazed at how writers always step up to their times. And this year, again, abroad, I read beautiful works by Barbara Kingsolver, Zadie Smith, and Paul Lynch. Many of the writers were here at this festival.

I want to mention Merve Emre’s criticism in the New Yorker. If you love books, if you love ideas, you must read her.