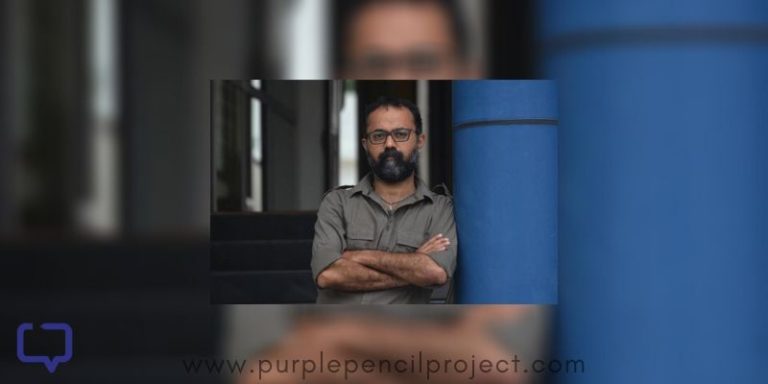

Ranjita Biswas is a journalist, writer and translator of fiction from Assamese into English. She is currently based in Kolkata.

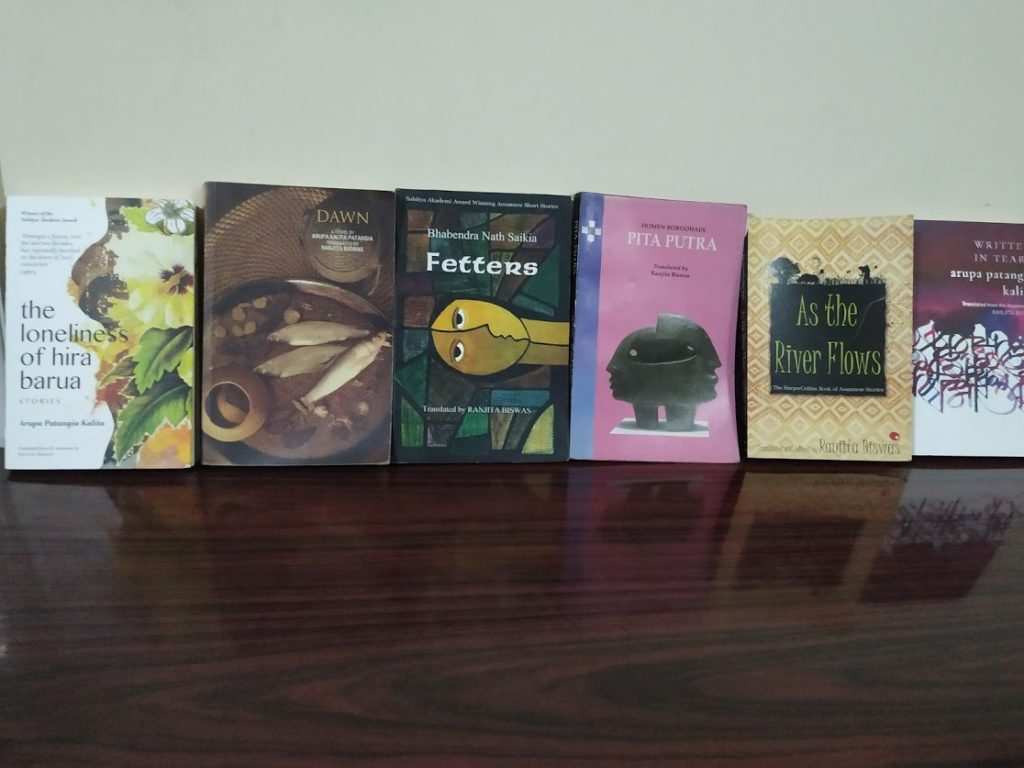

She is the translator of Written in Tears by Arupa Patangia Kalita, a collection of novella stories from Assam.

Rupal Vyas caught up with her to talk about the book, translating, juggling several writing careers, and more.

Did you pick Written in Tears? What made you choose that book?

Ranjita Biswas: Written in Tears is not translation of a single book. It is a collection of stories selected from different volumes by Sahitya Akademi winner Arupa Patangia Kalita. It is built around the theme of conflicts in the Brahmaputra Valley during the tumultuous days of the Assam Agitation (andolan) against illegal immigrants beginning in late 1970s, continuing through the 80’s and extending even beyond, and its impact on the common people as it deteriorated into widespread violence perpetrated by some sections of the agitators. The idea germinated an in free-wheeling discussion with editors at Harper Collins.

Written in Tears is set against a real, intense political reality of conflict – was it difficult to transport that world, that is so specific to Assam and its socio-political reality, and the language of that reality, into English?

Ranjita Biswas: For me personally, it was not difficult to resonate with the writer’s look at those times because I was in Assam during that whole period.

My early years started in an Assamese medium school. So the language was part of me both in school and at home. Later too while studying in English medium institutions, I did not lose touch with Assamese literature and continue to even now while living in Kolkata where I speak Bengali all the time by reading Assamese books and magazines. As a journalist, I contribute to English language publications, so the two way process is always on.

You have written widely about travel, about the Brahmaputra, folktales – what does it take to be able to authoritatively write across such diverse topics?

What is your research process like, if you have one? What are the sources of research you rely on?

Ranjita Biswas: From my school days the two areas that interested me most were reading and travelling. They used to figure in the essay we had to write on ‘Your Hobbies’, a perennial favourite with teachers. Growing up in a small town in upper Assam, and later in Shillong, global travel – so popular today – was not in our middle class domain of expectation. I frankly never foresaw that I could indulge in this hobby rather extensively as a journalist and travel writer.

Travel opens the mind, brings in myriad experiences, and an opportunity to meet diverse sections of people; that’s why I like to travel, and write on them.

Being from the Assam Valley I know how the Brahmaputra is embedded in the Assamese mindset. In my travelogue Brahmaputra and the Assam ValleyI have focused on the socio- cultural life of Assam vis-a-vis the mighty river rather than on a journey down the river. Folktales and songs, legends about the river, history – all come into it.

I could write the book because I was familiar with these ethos. But of course, in non-fiction books like this one has to quote the sources to authenticate. Usually, I read up as much as possible on a topic I decide to write on, online or otherwise.

Libraries are good sources. In Kolkata, the Asiatic Society Library, the National Library, etc., have some rare books on the North East. I also spent days in Guwahati’s State Library for the research work.

I also spoke to many veterans, and folklorists too. Actually the research process takes more time than sitting down to write.

For my travelogue Notes from a Spanish Diary, I augmented it with research through online sources, speaking to people and guides whom I had met during my solo travels in the country. Incidentally, I also learn Spanish on the side and it helped a lot. I didn’t want it to be a ‘travel through the destinations’ kind of book, there are enough guide books in any case, but a cultural- historical look at the Iberian country.

Whenever I could, I brought in an Indian or Assamese contextual anecdote to give a more intimate feel to the narrative.

For readers looking to be acquainted with Assamese literature, what translations would you recommend?

Ranjita Biswas: A good introduction would be, among others:

- Jnanpith Award winner Indira Goswami’s books like Saga of South Kamrup, The Man from Chinnamasta, The Bronze Sword of Thengphakhri Tehsildar

- Arupa Patangia Kalita’s Dawn that gives a glimpse of the Assamese society at the threshold of Independence and also the role the Baptist Missionaries played in development of modern Assamese literature which is quite unique

- Asomiya Hand Picked Fictions. Selected by the North East Writers’ Forum

- A Game of Chess (Classic Assamese Stories): Translated and edited by Dhirendra Nath Bezboruah

Over the last few years, translation has been enjoying a spotlight. Has that impacted your work, the acceptance of publishers etc?

Ranjta Biswas: Fortunately, the creative genre of translation in India has come a long way since Sahitya Akademi launched its programme in the mid- 50s to bring bhasha literature to readers through translations. Today, many prominent publishing houses in India have consciously taken up projects to bring regional literature to a wider readership. In the process, the ‘invisible’ person i.e. the translator, has also been able to step out of the shadows to garner due recognition.

Even a few years ago, the name of the translator never appeared on the book cover; today it does.

This recognition, long overdue, has definitely impacted translators. Having interested publishing houses on board encourages the translator to carry on the work. After all, who wants a labour of love, which it is mostly, boxed up in a drawer without being able to reach the reader?

With an increasing number of translations all around the world and a translated work even winning the Man Booker Prize in 2016 (South Korean writer Han Kang’s The Vegetarian translated by Deborah Smith) and many major awards in the field introduced today it is an apt recognition of the genre. I can also mention the four-volume Neapolitan saga by Italian writer Elena Ferrante beautifully translated by Ann Goldstein, which became an international best seller. Translations of literary works will definitely go from strength to strength in the foreseeable future.

What are some misconceptions around translators and translations?

Ranjita Biswas: First and foremost, I consider the expression ‘lost in translation’ is more a cliché than a real issue today. Without going into the endless debates about whether a translator is doing justice to a text, it is well to remember all translations are “approximate.”

Moreover, it is undeniable that translation is the only way, whether in a multilingual and multicultural country like India, or the diverse world, to get introduced to the literature of another region.

I was able to savour, and continue to, some of the best in the world literature and Indian regional literature only through translations.

What are some of your favourite titles that you wish to translate someday?

- Astitva, novel, by Anamika Bora

- Satyasujrjya, short story collection, by Geetali Borah

- Gajaraj Prem aru Banditwa, novel, by Purabi Bormudoi

Being a translator and a writer yourself, what do you prefer out of the two and why?

Ranjita Biswas: Actually, both. I consider translation to be as creative as writing my own fiction- short stories, children’s fiction, non-fiction, etc. I enjoy the challenge of the ‘dialogic’ process of cultural exchange while attempting to transfer the writer’s thoughts into another language.

I may also add that Assamese literature has a very rich tradition, particularly contemporary short fiction, but due to insufficient number of translations they remain largely unknown. So as a translator, I also feel as if I am contributing in some way, within my capacity, to give it a better exposure, like my fellow translators from the region.

Do you think social-media has considerably helped in the promotion of regional literature? What do you think of today’s readership?

Ranjita Biswas: Of course, social media provides a good platform for connecting with the public in this digital age. But whether it promotes regional literature considerably is debatable. True, announcements of new publications help to inform the readers but in general these are more about English language publications than regional literature books.

On the other hand, I see that writers, translators, interested readers have their own WhatsApp groups to discuss books and topics. That helps of course, but I am afraid they are confined to their own language groups.

Saying that, it’s heartening to observe that a growing number of online literature discussion groups, blogs, etc., have been making an effort to step out of the confined space and discuss books other than English language books.

As to the question of readership, it’s difficult to generalise. There’s such a vast world of readership today- in print or Kindle version, in this globalized world. I was surprised when an American woman contacted me after picking up Written in Tears at an airport bookstore.

In general, however, it’s often said that for most of the younger generation the attention span is short with so many multi-media attractions. As a result, books tend to be segregated, even by publishers, targeting certain segments.

I also observe, and many of my fellow Assamese writers agree, that there is a kind of homogenization in reading habits among the younger generation, perhaps due to the prevalence of English medium schools, and interest in their own bhasha literature is on the wane, at least less than what was when we grew up.

What advice do you have for aspiring translators and writers?

Ranjita Biswas: Advice would rather be a self-congratulatory term.

As a translator I feel that a translation works better if the translator is able to relate to the story personally. Constant interaction with the author is important too, to clear the cobwebs of doubts, interpretations, etc.

But of course, it also means more responsibility for the translator. To translate is not only to transform the text from one language to another, but also to bring out the nuances, the ras–flavour, of the original writer’s work, as far as possible. Many even like to call it ‘transcreation’.

It is also vital to keep up with the language as it evolves. I have found myself that contemporary Assamese language has evolved in many ways, absorbing new words, and themes wider in range than when I started out almost three decades ago as a translator. The style-sheets of publishers have also changed a lot, and it’s nice to see regional flavours retained or incorporated in translated works these days.

To add, I have read umpteen times about writers who say discipline is necessary to hone the craft. Many prolific writers swear by a set routine -that everyday these many of words have to be keyed in or so many dedicated hours need to be put aside, etc., whereas some take it as it goes, pottering around for days and then going frenziedly as the impulse to write takes over. I think the writer herself or himself knows what works. I write sporadically too, unless I am into a book but read a lot in between. Thankfully, my training as a journalist remains, and till now I have rarely overshot a deadline.

One Response