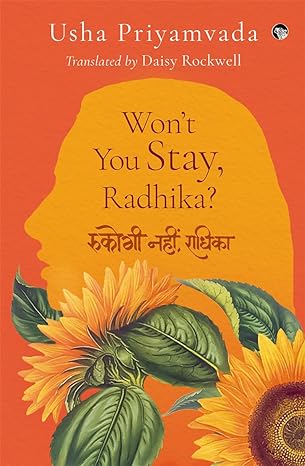

Anna Lynn reviews Won’t You Stay, Radhika, originally written in Hindi as Rukogi Nahi, Radhika? by Usha Priyamvada, and translated into English by Daisy Rockwell.

Introduction

This is the first novel written by a woman on the diaspora experience, as far back as 1967 by Hindi writer, Usha Priyamvada. It is brought to the English reader’s imagination through a splendid translation by Daisy Rockwell, the translator of the Booker Prize novel, Tomb of Sand.

Plot, Protagonist, and Radhika

As the title, Won’t you stay, Radhika? implies, in this book, we follow the interior narrative of the protagonist – Radhika, who returns home from her art history degree in America. Through her reflections on her strained relationship with her father and feelings of alienation from a place she once considered home, we learn the back story. Radhika left for the States with a male journalist and friend, upon hearing the news of her father’s remarriage to a woman of her own age.

In her travels back home, Radhika finds herself confronting many crossroads of confusion – does she want to get married to one of the three men in her life, how can she find a balance between her experiences in the West and her present return to a country, still struggling to accept the global idea of modernity. And most pertinent of all – will she reconcile with her father?

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Themes and Notes on Translation

Although the novel does not promise a passionate plot, the reader is hooked onto the story, simply because of the position of the protagonist – a woman in her late twenties, as yet unmarried, who finds a home for herself, and also has enough financial savings of her own – set in the conservative patriarchal society of cities which have freshly awoken to the freedom of the 60s, post-independence.

Radhika initially finds herself within a liminality of belonging – an embarrassment for the homeland against the close scrutiny that Customs imposes. The focal point of the story remains the father-daughter relationship fraught by the presence of a contemporary stepmother. Although this seems intriguing, the narrative addressal of her “Electra complex”, feels like an overstretch of this particular theme. Yet it influences the constant anxiety that Radhika feels towards the potential search for a suitable partner.

The narrative is straightforward and the translation attempts to hold the soul of the original Hindi. It also tries to capture the ennui of the protagonist and the reader feels Radhika to be unlikable, even tiring, initially. The reader soon recognises this as a reflection of the state of her multiple confusions.

In parts, Radhika is narrated through the eyes of others – a foreign expatriate who returns to his own country (Dan); an Indian man, well established at work with a foreign-owned company (Akshay); and another diaspora returnee (Manish)– the one who most resonates with the feelings of alienation that Radhika feels with reverse culture shock. Her own inner psyche is also well described in relation to her unmarried status. Interestingly, the comparison between accepted norms of companionship within the US and that of India provides yet another diasporic state of confusion that Radhika carries within her.

One is glad that although the many irritations of suitors and fathers and brothers abound her, Radhika still holds her ground. The setting is also heavy with the pervasive bourgeoise comforts of upper middle-class families. Glimpses of modernism come up – in Radhika’s replies to friends and relatives who get too cozy about her unattached marital state, in the description of sarees, rooftop romances, coffee house meetings, the lackadaisical mentioning of the labour of ayahs and domestic workers for every single correspondence/house visit. To a contemporary “woke” reader, some of the descriptions of jealousy, one-upmanship, and waiting on women, might feel old-school.

Recommended Read: Daisy Rockwell: Translations, Booker and the way ahead.

Favourite Quote from Won’t You Stay, Radhika?

She walked around the closed compartment twice and then went and stood in the corridor. She was the only person awake there, the only person awake on the train in the middle of the night. Nothing was visible outside in the deep darkness, only the sparks from the friction between the wheels and the rails flashing like fireflies (27).

‘…Then suddenly I began to feel horrible living there, and I felt I couldn’t find peace until I returned to India.’

‘And did you find peace?’ Manish smiled.

‘I did not,’ said Radhika sadly. ‘I often think of the title of that Thomas Wolfe novel, You Can’t Go Home Again. I’ve become a bit strange: I’m neither happy there nor here.’ (109)

Final Verdict

The book dawdles along within the first fifty pages, but sticking along will provide some interesting insights into diaspora differences, upper-middle-class dinner conversations, and the nature of Indian marriage customs within this society. It is a post-colonial novel and has humorous instances, but one wonders why it comes too late.

Towards the end, we realise the book reads as a reflection of two women in relation to a man – father to one, husband to another. A statement on the different kinds of loneliness and how society chooses to judge and alternately punish both of them.

Much is left unsaid, but direct allusions to the ideological understanding of experiences feel a little far-fetched and unnatural in terms of a theorizing of experience (reverse culture shock, electra complex, etc). However, in order to be transported into a time and social locality of the overseas returnee from an upper-class background, and from the perspective of a woman at that, the book is a wonderful read.