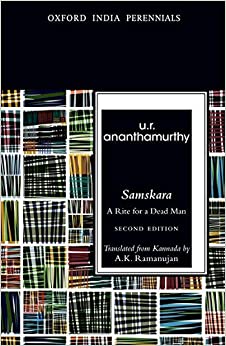

Translated from Kannada by A.K. Ramanujan

Samskara, originally written in Kannada in 1965, sheds light on the caste system and ways of Brahmanism in the contemporary world. The word ‘Samskara’ has several meanings: rite of passage, ritual, transformation as well as death rites. This short novella, it refers to the death rites of a man as well as the personal transformation of a renowned man living in a community that refuses to change with time.

The Plot

Samskara begins with the death of a sinful Brahmin, Naranappa, in Durvasapura, a close-knitted community of Brahmins. Naranappa has renounced Brahmanical ways and spent his time with Muslims; enjoying his time drinking, fishing in the temple pond and eating meat. The most apostate of his actions, however, was breaking up with his lawfully wedded wife to take a lower caste woman, Chandri, as his concubine. Despite his blasphemous ways, the Brahmins never excommunicated Naranappa, and he remained one of their own. In death, this becomes a problem because only a Brahmin can perform his last rites and nobody is willing to do that.

The polar opposite of Naranappa is Praneshacharya, who is highly revered by everyone in the community for his knowledge of Vedas and religious texts. Though not yet forty himself, he is thought to be too wise for his age and everyone in the agrahara consults him for any decision. No one can eat until the body is disposed of and nobody is willing to perform the rites for the fear of inheriting his sins. He retreats to his holy books to find answers to the problem at hand.

Ananthamurthy portrays a society full of superstitions and a total lack of compassion that is on the verge of collapse.

“Not a human soul there felt a pang at Naranappa’s death, not even the women and children. Still in everyone’s heart an obscure fear, an unclean anxiety. Alive, Naranappa was an enemy; dead, a preventer of meals; as a corpse, a problem, a nuisance.”

Major Themes

Samskara renders the conservatism and selfish mindset of the traditional Brahmin community through the rise and fall of the protagonist Praneshacharya.

In order to encourage the men to perform the last rites of Naranappa, Chandri offered her gold ornaments that caused many of the Brahmins to change their minds and began fighting.

Praneshacharya has never had intercourse with a woman in all his life. His wife is an invalid and ill person and he has dedicated his life to tending to her. However, there are no unselfish good deeds! He deliberately married her considering his sexless marriage as penance and sacrifice to attain moksha.

Ananthamurthy does not shy away from his criticism of the Brahmin way of life. The stubborn foolishness to follow sacred laws causes Naranappa’s body to rot. The horrible stench invites rats and vultures making the agrahara unbearable for living in.

The community places ritual over basic human rights: a decent funeral for a dead man. The most interesting character of the book is Naranappa – The anti-Brahmin standing against the most-Brahmin Praneshacharya and Brahmanism itself.

Naranappa dies in the first scene but his presence is ubiquitous throughout the book (For fans of Daphne Du Maurier). Despite his profane ways, there is honesty in him. This honesty, when pitted against the hypocritical ways of the Brahmins, makes Praneshacharya wonder if Naranappa will reach God first.

The depiction of women and lower castes is a sad tale of its own. The lower caste women are mere objects of desire to upper caste men.

The critical point in the book is when Praneshacharya sleeps with Chandri. It brings out the obscure desires of his heart to light. He is now unsure of his own identity, authority and needs.

Circumstances force him to question his austere ways. One can view the book in two parts – before Praneshacharya’s time with Chandri and after that. The nature of the novel changes the philosophy and raises some poignant and timeless questions. However, Ananthamurthy does not offer any solution – the book remains open-ended.

Conclusion

Praneshacharya, in trying to solve the dilemma of who should perform the death rites (samskara), begins a transformation (samskara) for himself. A rite for a dead man becomes a rite of passage for the living. The afterword by A.K. Ramanujan in the book is brilliant, explaining the trajectory and the inner meanings of the events in the book that will benefit non-Indian readers greatly.

Rich in allegory, Samskara is a powerful tale about a caste system that challenges its staunch followers and effectively proves that it has no place in modern society. Written almost 6 decades back, it is very much relevant even in the present times. Readers should explore books of this kind more to bring social change to the omnipresent caste system of India.

Favourite Quote

“We shape ourselves through our choices, bring form and line to this thing we call our person.”

3 Responses

Lovely review. This book remains on my tbr. This seems a book for our times.

The novelist obviously ” truth teller ” .