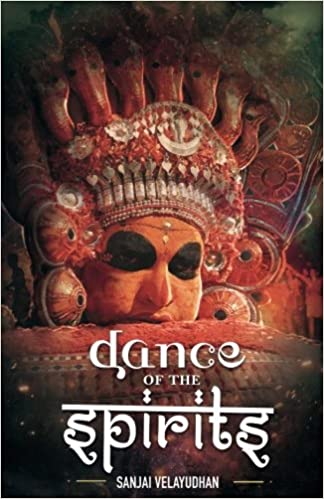

Sanjai Velayudhan’s Dance of Spirits opens with the promise of a culturally rich book but quickly dives into a sexist narrative, leaving the reader with a bad aftertaste.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Introduction

Folklore and rituals in India have mythic narratives woven into them. To enter this world is a surreal experience of history and culture passed down through the ages. The beauty of folklore is that every narrative practice also holds the power to subvert social hierarchies through performance.

Sanjai Velayudhan’s Dance of the Spirits presumes to enter this world through the practice rituals of Theyyam, a ritual form of dance worship practised in Kerala. However, his protagonist, Krish’s casteist NRI returnee gaze, coupled with misogynistic storytelling turns it into a recipe for a headache.

Plot: This Dance begins too late

The reader is introduced to the protagonist, Krishnan (Krish), his wife Lakshmi, and her upper-class family as they visit a temple. They perform the rituals for the salvation of the soul of someone called Maria who seems to have been Krish’s lover.

We travel back in time to when Krish comes down on a trip to India, to conduct research on the folk ritual of Theyyam. A book written by a friend inspires this visit. As he makes his way around Kochi, the chapters flow back and forth in time to introduce us to the circumstances of Krish’s marriage and past relationships. As Krish navigates to Kerala, the writer uses the stream-of-consciousness technique to introduce trivia on Kerala’s cultural history. However, Krish is unnecessarily classist and casteist in his interaction with drivers, hotel staff, and local guides.

Take this line for instance, which is used to describe the waiter: “His shoes weren’t polished and looked as old as him. From my mannerisms, he probably guessed that I lived abroad. He treated me with a little extra respect…it felt good.”

Or this outright casteist attitude: “Anthony smartly chose to sit away from us and eat. Despite being a modern professional, I had my reservations sharing the same table with a ‘driver’.”

When he meets an old friend Alex and a tourist – Maria, who is incidentally conducting research on Theyyam – the narrative picks up speed. The rampant sexist commentary does not relent even when the protagonists finally reach Kannur – where the Theyyam performance is to take place.

The ancestral property they reside in has a sinister history and practice of snake worship. The location is the site of various plot lines unravelling towards the climax. It involves several instances of sexual infidelity, the discovery of a murderous history, and many myths of black magic.

Theyyam Theme Analysis

The stream-of-consciousness narrative brings in historical trivia, triggered by objects in a hotel room, car rides, and flashbacks of memory. While it can be an effective technique when done with care, Velayudhan’s Krish seems to employ it specifically to inject his knowledge of history and culture. This can seem easy for a new reader, but feels forced and dissonant to seasoned readers.

While the novel boasts of a setting amidst the mysticism of Theyyam, serpent gods, and secrets of the past, it is only towards the very end that the plot enters this territory. Theyyam is a folk religious ritual that invokes possession by spirits in the course of worship. The spirits are often women who have suffered violent unnatural deaths. This ritual worship is unique in that it crosses the fault lines of caste and gender through religious performance. Barring a few conversations of tastefully written information on these sacred/profane ritual practices, much of the text is laden with uncomfortable sexual undertones that objectify various women characters and pander to the ego of the insecure protagonist.

Folk ritual history is badly woven into the climax. The setting preempts an air of magic and sinister histories. However, to a reader of literature, the succeeding events appear as a badly written plot. The horrific end feels more comical and ridiculous than of any real merit.

Insufferable Instances

The moral and intellectual superiority that Krish uses to colour this first-person narrative is tiresome in its patriarchy, that of an NRI returned, know-it-all, takes-himself-too-seriously man. The themes of glorified infidelity, his perspective on “five-star hotel” service in “English” and the occidental fascination with the rituals of Theyyam are overdone. His ignorance of casteism is most annoying. Krishnan seems to think that we currently live in an India rid of caste hierarchies simply because he is married to a Nair woman.

Sanjai Velayudhan has brashly written the character of Krish. The protagonist retains his pompous ego, struggling with the insecure fantasies of a jealous wife. The character himself assumes this, like other responses in the novel. He treats her with all the possible traits of toxic masculinity – lying, delaying phone calls, and sexualising her body. Throughout the novel, there is a continuation of this problematic description of the bodies of several other women. He even refuses to eat meals just because he’s angry. Every woman’s character is written with a limited typecast femininity. Krish is obsessed with creating an alter-ego against this. In one instance, he even takes pride in calling himself a male chauvinistic pig.

Krish’s observations stereotype Malayali culture and misuse his social status. The writing itself is mediocre with cliched adjectives than original prose. The far and few metaphors are soaked in sexist objectification – going so far as to use “dancer’s hips” to describe winds in the night.

OV Vijayan’s Khasakhinte Ithihasm is a far more nuanced and subtler text. It also deals with the magic and mythical surrealism contained within these rituals and the lands surrounding them.

Final Verdict

If you:

- are into historical trivia, specifically of Kerala and its cultural history

- have a fondness for the myth and ritual histories, of Kerala

- want a quick read to break the monotony of heavy literature

and

- don’t mind a badly written book

- narrated by a sexist protagonist with an inflated NRI ego,

you could try reading it.

If not, best stay away.