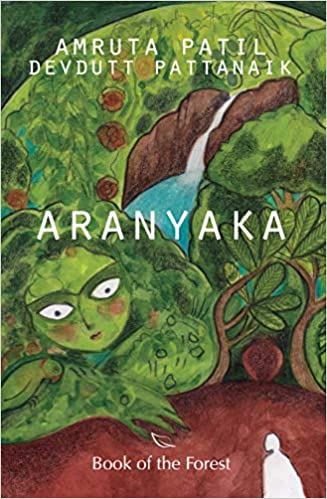

Aranyaka is a mythographic tale re-written through a feminist lens, weaving pre-Vedic concepts with lessons gathered from Aranya.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

What place does a large woman inhabit in the annals of myth and our present spaces of interaction? How does she make and break traditions – defined for herself and other women in the spectrum? Which colours would illustrate this reinvention of a mythic tale set in the deep forests of pre-Vedic lore? How would these myths read, when renewed with love and written in art?

Aranyaka – written and illustrated by Amruta Patil, with concepts by Devdutt Pattanaik – embodies all this and more.

Narrative

Katyayani the large – Aranyani, keeper of the hearth, containing aranya in her body, thought and practice, narrates Aranyaka. The central narrative borrows the old tale of Rishi Yajnavalkya, and his two wives – Katyayini and Maitreyi. Yajnavalkya was famous for his battle of wits against female intellectual Gargi, at the court of King Janaka. This rewriting is however the story of Katyayini, and through her footsteps and sight –– the story of Aranya itself.

The narrative commences from the deep beginnings of time, growth and hunger of the earth. The forest side brings us to Katyayani and her exile from the tribe. In the depths of Aranya, she forages for food and learns the secrets of the forest. Soon after, she finds Yajnavalkya and creates a settlement to form a heart with him. Her home is two things at once. It is a microcosm of the secrets she has gathered from the forest. It is also the site of an unfurling for herself and Yajnavalkya – in their journeys as partners and individuals.

Yajnavalkya is a man who thirsts for knowledge. Their conjugal journey begins in mutual collaboration to farm the fields. In time, Yajnavalkya settles as Guru and Katyayani as nourisher of those who come by their grove. The arrival of the Weaver and the Fig most significantly shapes Katyayini’s wisdom. Based on the mythic characters of Gargi and Maitreyi, The Weaver proves to be an intellectual match to Yajnavalkya. The Fig, an asexual garland maker, allures all of them with the wisdom of her songs and quiet observations.

Aranyaka as Interweaving richness

Each person entering the grove influences Katyayani’s gathering of wisdom and sense of self. Her observations of life, rituals, people and interactions are a larger reflection of Aranya and its manifestation within human relationships. The plot leads up to the debate at Janaka’s court and the concluding events will reveal the paths that await the central characters and muses of philosophical reflection – Yajnavalkya, the seeker of truth, Katyayani, who finds it in the forest and in her kitchen, The Weaver, seeker of answers, and The Fig, garland maker, holding wisdom in quiet observations.

Thus, Aranyaka’s narrative is neither folktale nor myth. It is an interweaving of stories and reflections in art and life seen through the gaze of Katyayani, the Aranyani. It is at its core, a feminist retelling of concepts and narratives referenced from pre-Vedic lore.

“Within each living scintilla, there is great fidelity to life, and great reluctance to die. In aranya, there is great violence, but no violation.”

Aranyaka, 9

Visual and Mythic References

Aranyaka’s genius lies in its duality, presented as one. It subverts patriarchal myths and simultaneously encapsulates pre-Vedic conceptual lore within story and art. A concept is embedded in each page of the story. They are wide-ranging and referenced from the Upanishads to the Vedas. Amruta Patil’s art contains elements borrowed from various ancient histories and mythologies. Weaver’s character is designed with elements from the statue of the Dancing girl from the Harappan Civilisation. Katyayini herself is referenced from the trope of the Village Goddess. Moreover, The Fig embodies elements of the Bhakti poet Karaikal Ammaiyar. Several stills in the book also use Meso-American and Egyptian mythological references.

Art and Design

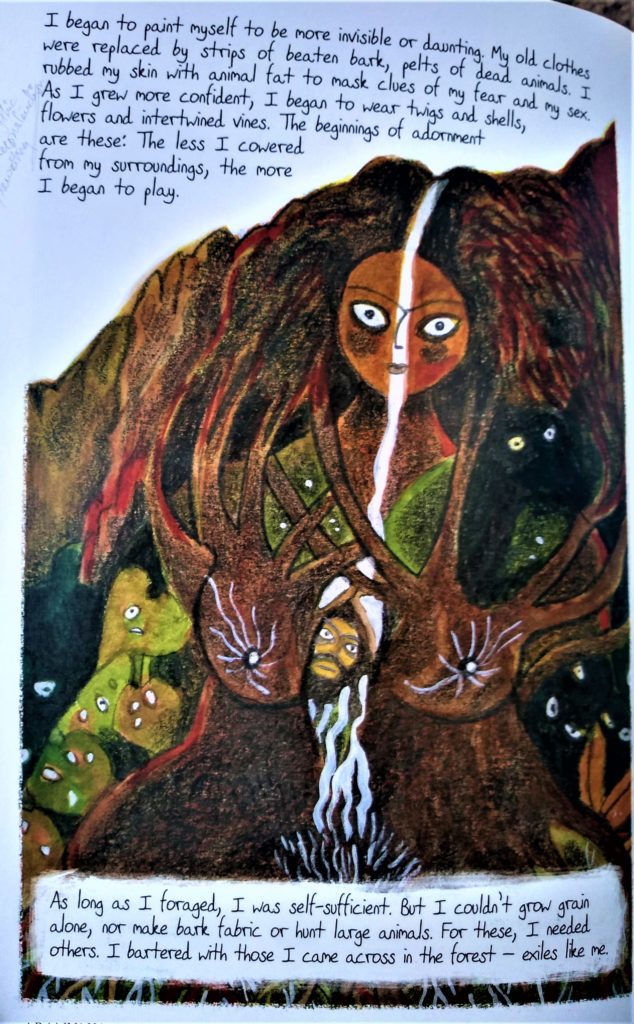

Every detail of the art holds a feminist mythological rewriting. Each page is designed to characterise concepts and thoughts using clothing, food, objects, and colours. Some pages are tapestries of their own. They range from the gathering of bodily hair as Katyayani steps into the forest; to the spreading of flowers and hair as Katyayini forms a bond with The Fig. She has deliberately used light, watercolour and water-soluble pencils to create the details and colours in the novel. As a whole, the graphic narrative is saturated in folkloric imagery of the Vedic past.

Art is an embodiment of writing. Animal and plant motifs recur as metaphors for the human character. The panther signifies Katyayani’s alter ego and sparrows feeding on grain signify a search for wisdom. Concepts like analysis (Sankhya), synthesis (Yoga), love (Prema), non-duality (Advaita), and duality (Dvaita) are explained through art. And pages turn into tapestries of single colour palettes and signs. A careful and loving reader can discern these elements within the graphic narrative.

Picture Credits: Anna Lyn

Best Quotes

“I began to paint myself to be more invisible or daunting… As I grew more confident, I began to wear twigs and shells, flowers and intertwined vines. The beginnings of adornment are these: the less I cowered from my surroundings, the more I began to play.”

Aranyaka, 28

Note to the Reader

It can seem that Katyayani embodies a one-dimensional female archetype of the dutiful wife and homemaker. The reader may conclude that she is a simpleton, representative of stereotypical qualities associated with women of the hearth. A careful reading reveals her redefinitions of characteristics assigned to women of the hearth. She defines adornment, settlement, caretaking, motherhood, and her own individual spirit within coupledom. These perspectives subvert patriarchies concealed in myths that dictate social and ritual norms. Her relationship with The Weaver and The Fig, breaks binary norms of sexuality and romance. Their histories and characters display spectrums of gender identities in individual existence. Katyayani’s knowledge from the grove of Aranya seeps into the knowledge that Yajnavalkya contains. It forms him and plays an independent role in the narrative. In this way, she refutes a possible one-dimensionality.

“Forest stories are mostly about men – their setbacks, triumphs. One never hears of the ill-equipped women, because those stories do not last long or end well. Rarely, one hears of aranyanis like me, women who contain aranya within them.”

Aranyaka, 122

Conclusion

There are women we discover in stories that create whole new worlds of possibilities for existence. We return to them over and over again. Aranyaka contains these women in writing, art and in spirit. The truth of this is perhaps held in the final pages of this graphic novel. Knowledge systems may belong to men like Y, but wisdom is contained in Katyayani’s simple quests. She grows and observes, and learns to hold lightly, the dance of existence in commune with natural elements.

Aranyaka teaches how.