Amritesh Mukherjee from Team P3 was in conversation with Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari at the Jaipur Literature Festival, 2025.

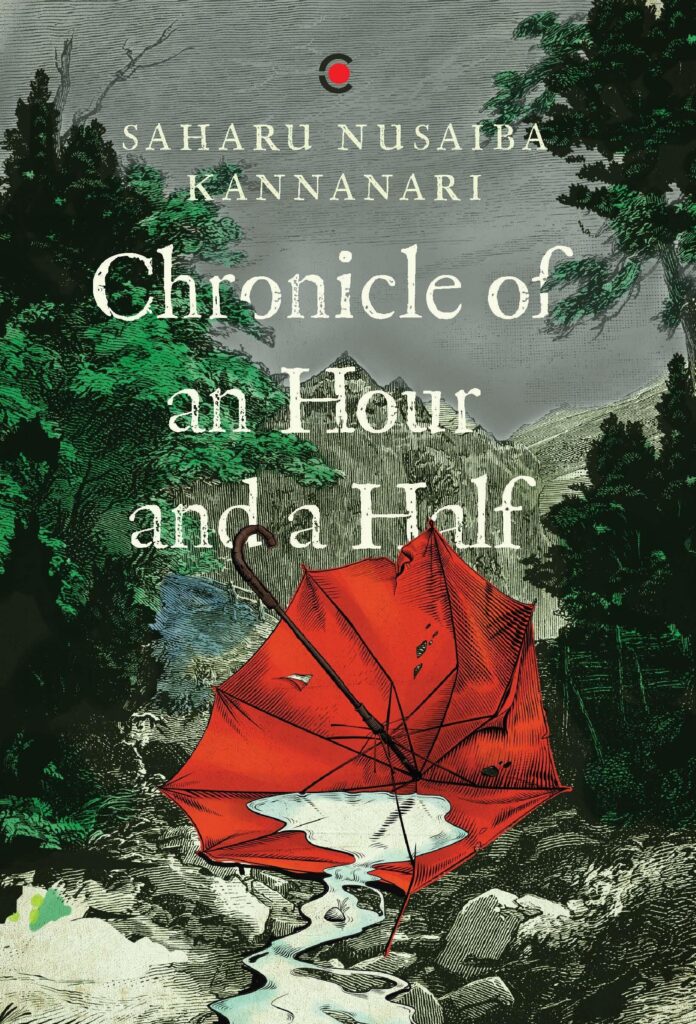

If you’ve ever been to the Jaipur Literature Festival, you’d know the ceaseless hustle and bustle that is at the core of the festival. If you’re a journalist, that hustling becomes even more incessant. Amidst that epicentre of literary extravaganza, I met and conversed with Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari for a solid two hours. Perceptive and sharp, his answers picked tangents new and old, while digging up rabbit holes for the reader to go into. He talks about his writing process, caste and colour, the Indian society, his literary influences, the influences behind some of the characters in Chronicle…, and a lot more.

With his second book now out, Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari is one of the most exciting and refreshing voices in Indian literature today, and I’m sure you’ll discover through this detailed interview some of the reasons why. Edited excerpts below:

In Conversation With Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

Amritesh: I’m sure it gets tricky when people ask you about intention in your writing, or why you made a specific choice.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: Most of these are standard questions. Unlike non-fiction, you don’t always have something to “expand on”; you can only give your opinions.

It’s difficult to answer such questions because writing works slowly. We do shape our characters, yes, but looking back and attributing intention to every choice you make is to attribute a rigorous method to writing, which isn’t always how literature works. Creativity doesn’t come in footnotes and references; it’s writing a sentence, getting a thought right, and reworking it when you haven’t.

Creativity doesn’t come in footnotes and references; it’s writing a sentence, getting a thought right, and reworking it when you haven’t.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

The reason why you chose certain characters to narrate the story—why Funny, why the imam, why the kids—is simply because you’re trying to bring a village alive, choosing figures who can be representative of it in one way or another.

Children and teens, for example, are very difficult to write about: they don’t speak in rational, articulate sentences, or in many words. When you abandon articulation, choice of words, and rationality, craft becomes difficult—because craft depends on those things.

So, in a sense, more than well-thought-out “intention,” I’d say I wanted the village to feel as diversely represented as possible. Let’s take the character of Funny, for instance—he becomes important because he’s at an age—around seventeen—when a porn addiction is most likely.

He is useful to represent voyeurism, which, in a society where sexual curiosities are heavily repressed, becomes a source of perverse consolation. His age, as well as the family he belongs to, where his father decides what he must and must not do, also helped me reflect on a boy’s impulse to be part of a mob without necessarily being a direct participant in the violence, which he records using his phone. It is his age when he hasn’t yet completely lost his natural impulse that helps me put in his mouth a question like “Who can resist a mob?”

Jean Baudrillard has a book called Seduction, in which he reflects on the kind of attraction that Funny feels toward the mob. He says there’s something that draws people to a burning car. How do you explain, rationally, what makes people stand by and watch something burning? It’s a complex attraction. That attraction—someone watching a car in flames—is the attraction Funny has for joining the mob: looking, seeing, feeling thrilled and being carried away by the spectacle of an active mob.

But again, these are very rational questions, and I don’t think writing works that way. The simplest answer is that I never think of the why. When I write, I’m thinking of what and how. I don’t think there’s a need for a lot of why to write a story.

Amritesh: I was at a session with translators. They often ask what a writer “meant,” because a line feels like it’s representing something. One of them replied, “I just wrote it; it didn’t literally mean anything. You’re the one finding meaning.”

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: I don’t know the specific context in which this is said, but I have difficulty concurring with that statement. An author certainly means something when he/she writes a sentence, and this is what makes both translation and interpretation possible. In other words, an author cannot write a sentence and abandon responsibility when confronted about it, and to do so is to mock an invested reader, nor can a responsible translator circumvent such a question because a translator’s artistry is heavily governed by the fidelity to the text under translation, no matter whether that’s a literal or figurative translation.

Looking back and attributing intention to every choice is to attribute a rigorous method to writing, which isn’t always how literature works.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

A sentence doesn’t work in isolation. It is informed by the sentences that precede it and informs the sentences that follow it. This coherence makes an interpretation, or interpretations, of a given sentence very possible. And this is possible even when a given sentence is rendered deliberately ambivalent by the author. However, I’d caution that literature’s purpose is to create an experience, not to transfer knowledge. It’s made of what we already know, and it re-educates us, or, as Shakespeare says, holds a mirror unto ourselves. That’s the prime purpose of a novel: it should give the reader an experience, like music.

A novel is essentially an introspective document. If the novel is heavily concerned with social questions, it must place the author at the centre of his/her inquiry. In other words, in anything we investigate, the author must be the prime suspect. If we are born into a society, we naturally become a host of all that is going on in the society. If there is caste in society, we are most certainly governed by caste prejudices, which will manifest themselves in us in all its multifarious dimensions. If the society is patriarchal, every male member of the society will reflect it both in his thoughts and actions.

In other words, if you are a Savarna, you must have given a lower caste a Savarna experience. If you are male, you must have given a woman a male experience. Resistance comes later, and even as we progressively moult the unpleasant feathers of these oppressive social realities we find ourselves in, we must not delude ourselves into thinking that we are out of it. And this honesty is essential to novel writing. It should not be conceived as a venue to give vent to our sense of victimhood or preach righteousness. A good book of fiction is a struggle against this sentimentality.

To what extent can we really shed our privileges is a ponderable question that a mere novelist like me may be unable to answer. A full-fledged individual revolt may be strained by the sheer hostility from the family, the society, and the cultural apparatus. Change, I suppose, is a slow and lifelong and intergenerational process, and accessing truth in all its complexity is a sure first step towards a desirable transformation. This means that we must not hesitate to accept truth, and the truth is that if you’re not marrying outside your caste, you’re not a threat to caste, however radical your lip service is.

If you are a man who doesn’t take up roles that are traditionally assigned to women, you are not a threat to patriarchy. That’s why most progressives don’t upset caste or patriarchy. This is why I keep saying when the time for marriage comes, we all seem to know who to marry.

Children and teens are very difficult to write about: they don’t speak in rational, articulate sentences. When you abandon articulation and rationality, craft becomes difficult—because craft depends on those things.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

Most feminist men I know in my life don’t want feminists for a wife. Most upper-caste men and women I know in life are married to an upper-caste partner, even though they sound like Zarathushtras when it comes to rhetoric. And in the rare case of an intercaste marriage, the upper caste partner is almost always a woman.

Amritesh: You’ve stated in interviews that Faulkner influenced your use of multiple narrators and the first person. Was that the plan from the start, or did it evolve as you wrote until it felt like the right structure for the story?

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: I wanted two central characters—Nabeesumma and Reyhana—to speak in the first person. That led me to make other characters speak in the first person, too.

The simplest answer is that I never think of the why. When I write, I’m thinking of what and how.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

Second, yes, I was influenced by how Faulkner executed As I Lay Dying, which is set in the American South, with racial tensions and poor white Americans. His works focus on poor white Americans, not urban New York or New England whites.

The novel is narrated by fifteen characters. There’s a character, Addie Bundren. It begins with Addie’s eldest son, Cash, building a coffin; he’s a carpenter preparing a coffin for his mother, lying by the window, watching him, waiting for death, watched over and fanned by her daughter, Dewey Dell.

Addie has a deathbed wish: she wants to be buried in Jefferson, her familial cemetery. Her husband, who hasn’t been of much use to her, decides to honour her wish. After she dies, they transport her body there. It takes them nine days to reach their destination, her non-embalmed body rotting.

However, in the middle of the novel, Faulkner drops a monologue by Addie herself, already dead, speaking about herself. She’s not highly educated and doesn’t speak in an articulate way. The language is powerful and colloquial. Free, with its own syntax. The vocabulary is limited because, in the first person, vocabulary has to come down to the level of the speaker.

An author cannot write a sentence and abandon responsibility when confronted about it; to do so is to mock an invested reader.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

I was mesmerized by the craft and voice. It felt raw, someone speaking directly about her life. She’s uneducated; she married, lived her life, had children with her husband and a son from an extramarital affair, Jewel, with a pastor. The mother figure in Chronicle—Nabeesumma—closely resembles the mother figure in As I Lay Dying. That was the starting point.

As the idea progressed, I wanted to bring the village alive. For that, I needed many characters. Since I had in mind a short novel, the best way to do this was by multiplying speakers without making it chaotic. I reached around fifteen or sixteen speakers. The first draft had twenty-nine characters, but later I cut it down.

I never learned writing or editing formally. I just read books. I imitated the best available models. Influence is central to a writer’s development. Imitation helps. If you imitate great artists well early in your writing career, the cocktail of influence would eventually deliver you a style of your own. I read this in a Paris Review interview of Faulkner. He deprecates inspiration and says: Steal anything. Just steal. I don’t steal from people in real life, but I steal ideas. Faulkner told me to steal ideas, and I stole his.

Literature’s purpose is not to transfer knowledge but to create an experience. A novel should give the reader an experience, like music.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

There’s a book called The Anxiety of Influence by Harold Bloom. He excludes Shakespeare—says Shakespeare is above influence—though he concedes Shakespeare had influences like Chaucer and Christopher Marlowe. Shakespeare also used the Geneva Bible rather than the King James Version, which came later. Shakespeare had influences, but Bloom argues that Shakespeare swallowed his influences the way a whale swallows a minnow; they disappear. Marlowe gets consumed by that creative fire that produces Othello, King Lear, and Hamlet in a short span. That kind of creative power is unknown to humankind and remains unbeaten.

Ideas come from other people. Nobody has an original idea. Even Newton had precedence. Every knowledge system relies on back references. Someone always precedes. Someone explains something wrongly, which means someone tried to explain it rightly.

So to speak of style, which is also a by-product of influence. In time, I’ve come to intensely dislike exclamation marks and semicolons. I want sentences to have only two marks: period and comma. If editors allowed me, I’d take out inverted commas too. I dislike them because if you’re writing well, you don’t need them. In dialogue, if you’re good, you don’t have to write “he said,” it should be conveyed by the tone and context. When you get rid of that and write dialogue, it changes the quality of reading.

That’s why I keep saying Don DeLillo may be one of the greatest dialogue writers of the twentieth century. In Underworld, there’s a conversation between Bronzini and his sister; she’s old, has dementia, keeps repeating the same question. That’s real life: a demented person repeats. How do you deal with it?

How do you bring life to a person caring for a demented sister he loves? How do you deal with being remotely annoyed by your own sister even when you know she’s sick and can’t help it? How do you record a conversation between a demented person and a non-demented person who are deeply fond of each other? He does that. Only great writers can aspire to that and achieve it.

If a novel is concerned with social questions, the author must be the prime suspect in it.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

Narration is easier than dialogue. I was helped by reading plays. I’m a big Shakespeare fanatic. I haven’t spent a single year in my life without reading Hamlet ever since I first read it. His characters are so many and so well-etched that it’s impossible to access his true self at all.

Amritesh: Maybe that’s why people debate whether Shakespeare was one person or many—there are so many theories. Does that kind of speed and sheer output inspire you as a writer?

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: Haha. That’s why Coleridge, in his notebooks, called Shakespeare myriad-minded. Somewhere else, he also compared Shakespeare to a serpent which “writhes in every direction but still progressing.” That’s also why Ralph Emerson said that Shakespeare could tell apart in a child’s face its mother’s and father’s halves. He wrote thirty-nine plays with a hundred major characters and a thousand minor characters.

All his major critics agree that what makes him greatest, aside from the overwhelming rhetorical and cognitive merits of his writing, is his preternatural ability to create distinct characters who are utterly different from one another. But Shakespeare was one person, born in Stratford-upon-Avon, son of John and Mary, father of Hamnet, Susanna and Judith. The idea that somebody else wrote Shakespeare was an upper-class hoax and is total nonsense.

A good book of fiction is a struggle against sentimentality. It should not be a venue to preach righteousness.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

One of the major proponents of this hoax, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote a preface to his friend Delia Bacon’s book questioning Shakespeare’s authorship, later confessed he wrote the preface without reading the book. Borges discusses the Shakespeare authorship question in his 1964 essay titled The Enigma of Shakespeare.

So far as output is concerned, well. There are reasons why I tend to write short novels. I’m fond of long novels, but I don’t write them; I can’t afford to. If you are poor, you can’t sustain yourself as an English novelist in India without producing works, let’s say, every two years.

So there are two reasons to write short books. One: I don’t have the capacity to keep readers engaged beyond a certain number of pages. Two: it’s unsustainable, financially speaking, to write novels that would take five years to finish and another two to edit and publish.

I’m not a fast writer; I’m a slow writer. The reason why I am able to finish a book within the timeline I want to finish them is that I have a clear plot—a clear narrative arc, beginning, ending, major characters. I usually get my title very early, and my titles stay. A title gives direction. I usually have my last sentence in mind. It’s thrilling when a story ends exactly with the sentence you planned.

Amritesh: I love this line by Tagore: it isn’t simple to be simple. Reading you, I’m struck by your clarity of thought and how that clarity seems to ease the act of writing. There’s something beautiful in the way you pursue truth without over-interpreting it.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: Haha. As Mark Twain said, if he had time, he would have written a shorter letter.

When I say we must speak truth, I don’t mean discovery of truth easily redeems or uplifts. Truth may be complex, but not unreachable: it’s accessible to everyone, and we simply pretend we don’t know it or interpret away our prejudices with the help of social sciences. Truth has no redemptive properties unless it makes you see yourself anew in the mirror in all your nakedness, and this is rare because it requires immense courage.

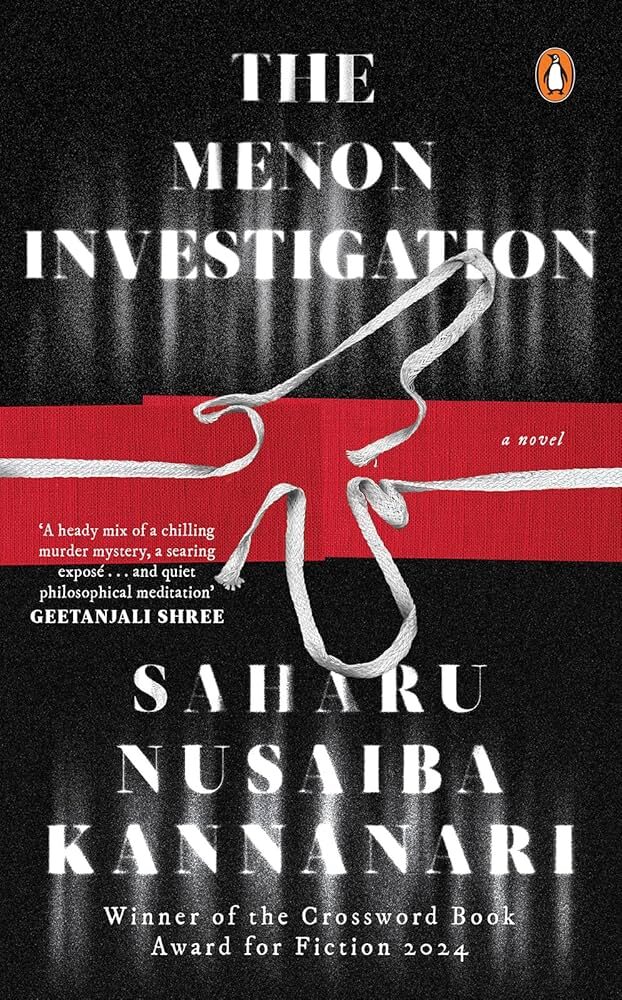

In real life, we lie all the time. Lying is an important part of life. In fiction, if it’s to be more than entertainment, you must speak the truth. That’s why Sadique (Reyhana’s husband, who in some sense informs my second novel, The Menon Investigation) never speaks in the novel. If Sadique spoke, Reyhana would appear very different. It would deprive her of the context I wanted her to place her in, which is a woman chained by the sheer force of patriarchy.

Sadique is deeply color-conscious. He hates his own body. His thoughts are shaped by a society that made him believe his skin color is inferior. So he leverages his financial position to marry a fair-skinned woman. This is a common trend where I live.

If you keep hunting for a morally perfect author, you won’t have a book left in your library, including the holy scriptures.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

He gets a fair wife in Reyhana. Reyhana is deeply color-conscious, too. She was fifteen at the time of marriage, and even at forty, she hasn’t grown out of that first thought: that she’s married to a dark man.

The truth about one’s condition in terms of caste, gender, religion, or sexual orientation doesn’t necessarily produce critical thinking on other fronts. Human beings generally tend to be super-focused on their own sense of victimhood, being over-alert about their oppression while continuing to be agents of oppression on other fronts.

There is an intense aesthetic deficit in our cultures. I’ve seen eight- and nine-year-old girls deeply troubled about appearance. Where do they learn to compare skin color? From society, from schools, families, television, movie screens, and from what’s fed to them. And the result is that a vast majority of the population is made to feel insecure in their body, unsuitable for desire. This gets especially acute in arranged marriages, where the darker the skin colour of the girl, the lesser her chance of finding a partner unless they offer a huge dowry. In other words the dowry goes down as fairer the girl gets.

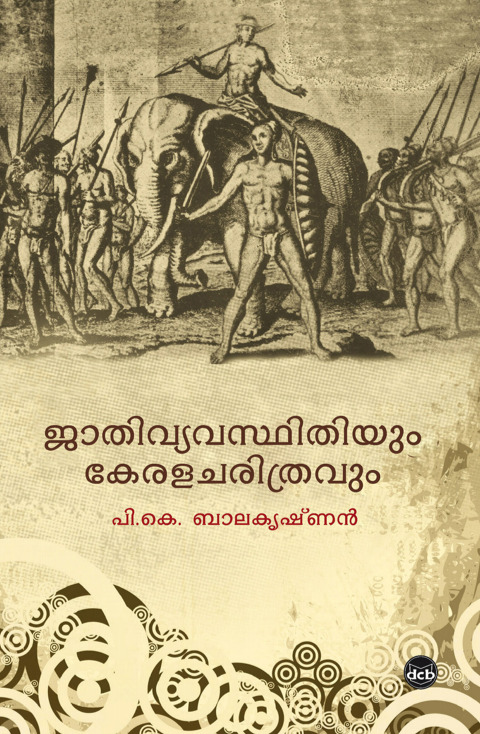

There’s a book on caste in Kerala by PK Balakrishnan, in an introduction to which Professor Dr Gangadharan of Calicut University remarks that those who speak about caste are seen as having an inferiority complex, a remarkably loaded and deeply offensive word which is so casually thrown around in our daily lives even by people who consider themselves highly sensitive. I’d venture that the same happens with skin color: the moment someone talks about it, it’s pinned to their skin and labeled as an inferiority complex.

There is no such thing as an inferiority complex so far as social questions are concerned. If a man lives in a perpetual fear that his wife is having an affair and may desert him at any moment, he can be said to have something akin to an inferiority complex (but I still find the word indigestible), but not with skin colour or caste. If a woman complains that men don’t treat women as intellectually equal, it’s not an inferiority complex but a legitimate grievance with an unchallengeable foundation in reality. Likewise, speaking of skin colour prejudices, which are deeply ingrained in our psyche and are tolerated and not talked about.

The most influential person in the entertainment industry, influencing upper-class people in north India, may be Shah Rukh Khan. Now this person for long has been an advertising icon for fairness cream for men. In the recent Lok Sabha election, Narendra Modi was upset about something Sam Pitroda said: South Indians look like Africans, North Indians look like whites, Northeastern people look like Chinese. Preposterously but predictably, Modi thought it was terrible to compare South Indians to Africans, but didn’t think it was terrible to compare Northeastern people to Chinese or North Indians to whites. And he thought this would help him deliver votes.

Influence is central to a writer’s development. If you imitate great artists well early on, the cocktail of influence will eventually give you a style of your own.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

There’s a standard template for matrimonial advertisements in Kerala: every ad would tell you the skin colour of the person, possibly to imply that they are looking for alliances from fair grooms and brides as well. It’s also frequent to see ads from so-called progressives saying religion and caste don’t matter, but with a disclaimer— “except SC and ST”. These ads appear every weekend in newspapers.

This is the society where I am placing my characters, and they will reflect all that is going on in society. One major theme of my second novel, The Menon Investigation, is colourism.

Amritesh: Your book has that line about a “ministry for WhatsApp affairs.” In an age where algorithms shape what we see, and even who we meet, how do you think this is changing society and the way people behave?

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: The internet has made all of us statemen. We have opinions on everything. We perform for a crowd. We expect likes and engagement, so much so that it has become a kind of barter system where you trade likes and shares. There seems to be something irresistible about the internet.

Ted Mooney said in the 1990s that we have an information sickness. I think we have a communication sickness now: the desperate need to communicate, the urge to check the phone to see if someone has messaged me or liked my post, and it triggers all kinds of unnecessary anxieties in people. They judge themselves by the messages and interactions they receive online. They post and share and like and forward. The end result is herd behavior.

There are of course tremendous positive impacts, of course. No one in the right mind will dismiss that.

In my novel, WhatsApp isn’t a major character. I’d say it has aided mob-making with its extraordinary ability to disseminate news. I wanted to portray primitive outrage in a technologically driven society. I wanted conflict to arise from something trivial, like an extramarital affair. That sets an individual and a community in conflict.

Truth has no redemptive power unless it makes you see yourself anew in the mirror—and that requires immense courage.

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari

Reyhana’s choice is personal. She’s forty. She can sleep with whoever she wants. She debates with herself over the appropriateness of her desire and overcomes the taboo. She doesn’t love him. She isn’t romantically involved. She’s doing it for pleasure.

SMS and WhatsApp make such relationships possible because communication is easy. You meet somewhere, exchange numbers—parents wouldn’t check that route. Indians are easy to turn into a mob, and our society still exerts enormous control over personal lives.