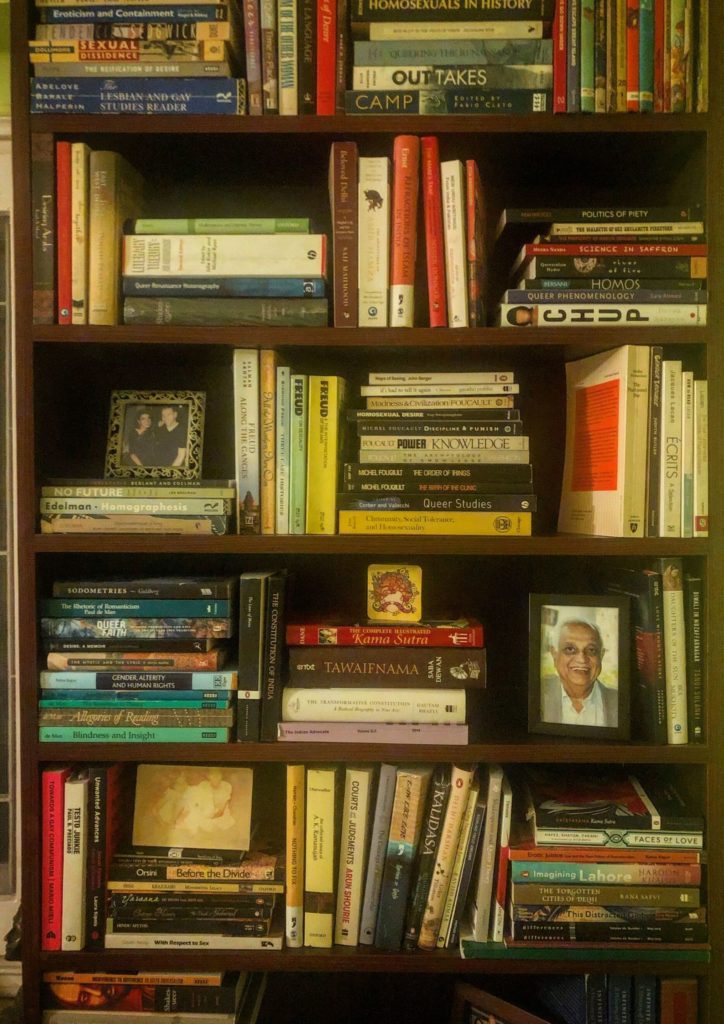

Madhavi Menon is a Professor of English at Asoka University and Director of the Center for Studies and Gender and Sexuality. She is also an author of several academic books such as Wanton Words: Rhetoric and Sexuality in English Renaissance Drama (Toronto 2004), Unhistorical Shakespeare: Queer Theory in Shakespearean Literature and Film (Palgrave 2008).

Her last book, Infinite Variety: A History of Desire in India, was published by Speaking Tiger books in 2018.

In this interview with Purple Pencil Project, she speaks about life as an academic, literature in the Indian classroom, and more.

Can you elaborate a little on your relationship with literature and teaching?

Madhavi Menon: I certainly grew up as a reader, they were important in the household I grew up in. My mother is a professor of English, so there have always been a lot of books in the house and I read the usual, like Enid Blyton and sci-fi authors.

I even founded a club of my own, I don’t remember what it was called, maybe Fantastic Four, Fabulous Four or Famous Four or something. I was inspired like that.

However, I didn’t always want to become a professor. I think at times I wanted to become the Prime Minister, if only I had followed that path, that would have been interesting! At some point, I actually thought of becoming a lawyer, I was very interested in the law. But by the time I got to college, I was fairly clear about what I wanted to do, and here I am!

How did you choose to be a professor at Asoka?

Madhavi Menon: When I was studying as an English major, the centralised curriculum, the fixed set of texts and the fact that there were only exams, annoyed us. At St Stephen’s we did write essays but none of us really put in any real effort; at the time, you could go through an English major without having written a single essay! This is criminal. Back then, I did not think much of it; I loved college, my peers, my professors and my life at DU.

When I returned after having lived in the US for 18 years, it struck me how odd that system of education was and I was sure I did not want to return to teach at a place like DU. I had a wonderful time there, no doubt, my mother taught all her life at the Kamala Nehru College in DU, but it was not for me.

There is a distinction between being a professor and a teacher, and I am a professor and I wanted to be at a place where being a professor was respected, where you did not spend all your time in the classroom, and also be able to sustain myself financially.

At DU, you could have your PhD in 16th century medieval poetry and teach TS Eliot or Samual Beckett; there is no respect for your niche.

Lucky for me, I stumbled upon Asoka, which has a very liberal outlook in which professors devise their own syllabi, based on their expertise and their specialisation. We teach twice a week, and the rest of the time is devoted to reading, writing and research of our own. This is what attracted me to the opportunity, that the classrooms would be interactive, where students would be considered to be interlocutors with the professors than recipients of their gyan.

These ideas are absolutely necessary to me in any academic climate and I was only able to return when all those were guaranteed to me.

How are literature and politics intertwined in your classroom?

In my classroom and in the classroom of many of my colleagues, there is no difference between literature and politics, as it should be.

Madhavi Menon: Historically, literature has always been at the front and centre when it comes to political thought and political activism. You look at any major protest movement around the world, if it’s centred in the university, it is always centred in the English department or literature department.

Literature has had an active engagement with what it means to live in the world.

And if you are engaging with what it means to live in the world, then you are engaging politically, and you are engaging with the politics. And by which all means, with the way in which we think, with the way in which we act or with the way in which we create certain structures that make life possible or impossible from day one.

You’ve written mostly non-fiction – what do you think the market for it is here? Have you considered writing fiction?

Madhavi Menon: No, no, no, not at all, I think I’ll be terrible at fiction. I don’t think about myself as a fiction writer at all. I think I am a very good writer, to sound utterly arrogant, but I’m good at writing non-fiction. I don’t do fiction.

That doesn’t mean that might not change, but right now, I do not think of myself as a fiction writer.

There are enough fiction writers in English, though I do believe the heyday of Indian writing in English is over, it lasted from Rushdie to Roy and since then while the numbers grow, nothing staggering is coming out.

My academic books on Shakespeare academic were not published in India, so I cannot tell you about the market here, though I doubt it will be very big. My books are priced in USD and they are horribly expensive, because that’s how it is there – academic books are too expensive which limits their markets there as well.

I think non-fiction books here in India are much, much better off than in the West, because they are widely available and are affordably priced.

My ‘History of Desire in India’ was, I think Rs. 599, started out at Rs. 499 and came out in paperback right away.

There are lots and lots of venues in which you can talk about your books and one of the things I love about being here is that non-fiction books are not considered elite or so far removed from daily life that they can only be spoken about in esoteric, secret gatherings. They are widely discussed, and they are widely read as well. I really think the market for non-fiction books here is huge and quite thriving.

What was your own introduction to gender and queer theory…was it part of instruction or did you stumble into it?

Madhavi Menon: It’s a difficult question, because I certainly never studied queer theory or feminist theory when I was in Delhi. There was no such paper on the centralised syllabus, though we did have a few professors at DU that were strong feminists and would bring up ideas of feminism now and again, but no we never really had any formal training in it.

Having said that, I recognised early on that there was a problem with a gendered existence in the world even though I may not have articulated it.

When I was 10-11 years old, I was the Editor of our colony paper, or no, the newspaper of our ‘road’. We were five kids who came together to start a newspaper. I came across a copy of the paper, and my first editorial was titled “Boys; something needs to be done.”!

I think I’ve always had an extremely keen sense of what it means to belong to and sympathise with people marginalised or downtrodden, in different ways, because we are not all marginalized in the same way at all, but marginalized in terms of gender, marginalized in terms of sexuality.

I’ve always had an interest in thinking about under-represented people. I think, given that interest, and given my interest in Shakespeare, when I went to the US to do my PhD, taking classes on queer theory immediately felt like coming home, intellectually. That there was finally a language that I had been graphing towards my entire life, and here people were actually thinking and writing and publishing about it – it was amazing to discover it.

Of course, that has changed in the interim in India as well, and more and more people are doing that kind of work now. But it’s still not a major academic field of study.

When did you first notice the queer elements in Shakespeare’s works?

Madhavi Menon:

I think its impossible to read Shakespeare without thinking about how queer the texts are.

I’ve always had a sense of how queer they were, a sense of the text playing with received wisdom, which of course is one of the most queer ways of being in the world. I always had the sense of them questioning castings that we take to be sacrament, which is of course another way of being queer in the world.

I’ve always had a sense of texts sort of critiquing the rigidity of gender categories, of allowing up to little sexuality in other, alternative ways, so I think I thought that way about Shakespeare, but again, as I said, not in a very disciplined way, until I thought of studying something formally.

Do you think there is a lack of adequate representation of Indian writing in the arts curriculum? Is there a need to change this?

Madhavi Menon: I don’t know what the papers on Indian writing are, but I believe, when I was studying there was nothing, it was zero. Soon after I graduated, I think they started introducing one paper on Indian writing in English, I believe there are many more options now. I don’t know in detail what it is, but I know there are many more options in the public university system. Certainly at Ashoka, if you are an English major, there are several options for studying Indian Literature.

Absolutely, there is a need to change this. I don’t know how much there is now, so when I say more I don’t know what exactly I’m saying. But I think you have to study the canon and you have to study multiple versions in which the canon has been refracted, absorbed, challenged in literatures that have grown up around the world. And ideally, one should study them in conversation with one another, not necessarily separating them out.

But yes, there needs to be many, many, many more kinds of Literatures, many more kinds of authors studied.

You had mentioned last year that you are trying to work on something about the Law of Desire. How is that coming along?

Madhavi Menon: Slowly. I haven’t done much on it yet, but this summer I’m going to have to find a way to start.

I’ve always been fascinated by the law. In History of Desire in India there is a chapter on the law, and I’ve referred to it in two or three other chapters as well, but I’m always fascinated by how lawyers dealing specifically with issues of sexuality were to themselves, how they hoped to be effective, how they hoped to work.

And I wanted to do an entire short book on it which is what I think I’m going to do and I want to just sort of pick a few cases that I think are going to be interesting for us to think about in relation to laws on homosexuality, marriage, adultery, on prostitution, on all these kinds of things, and just think how in each of these arenas the law tries to control desire and whether or not it succeeds in doing so.