Easterine Kire was born in Kohima, Northeast India. She studied at the North East Hill University and received a doctoral degree in English Literature from the University of Poona. Easterine’s works include poetry, novels, short stories and children’s books; her major works include A Naga Village Remembered (Ura Academy), which has since been reissued by Speaking Tiger (2018) as Sky is my Father, A Terrible Matriarchy, When the River Sleeps, Son of the Thundercloud, and her latest, A Respectable Woman, awarded Printed book of the Year by Publishing Next in 2019.

Excerpts from an interview we conducted with her

You are a pioneer of Naga literature in English; would you shed some light on the literary scene in Nagaland outside of English, in either Angami or Tenyidie, or other languages of the region? Are there writers from Nagaland, who you think should be read more widely outside?

Is there a version or equivalent of epic literature in Nagaland/north-east?

Easterine Kire: Outside of English, we have a very rich literature in the native languages. Tenyidie rapidly made progress from oral to written after Christian conversion which introduced writing and translation. In this day, the oral tradition is still to be found in the villages; casual visits to elders end in them narrating village history and lore, and this takes place in a very natural manner.

At the fireside gatherings in the dormitories for boys and girls, the elders tell the youngsters stories from the past whose purpose is to give them moral guidance. The highest forms of native literature is found in poetry; the language of poetry is so elevated that it could almost qualify as another language.

Poets never use colloquial terms; translation of oral poetry has to undergo two levels, first the translation to colloquial Tenyidie, and then the translation to the target language.

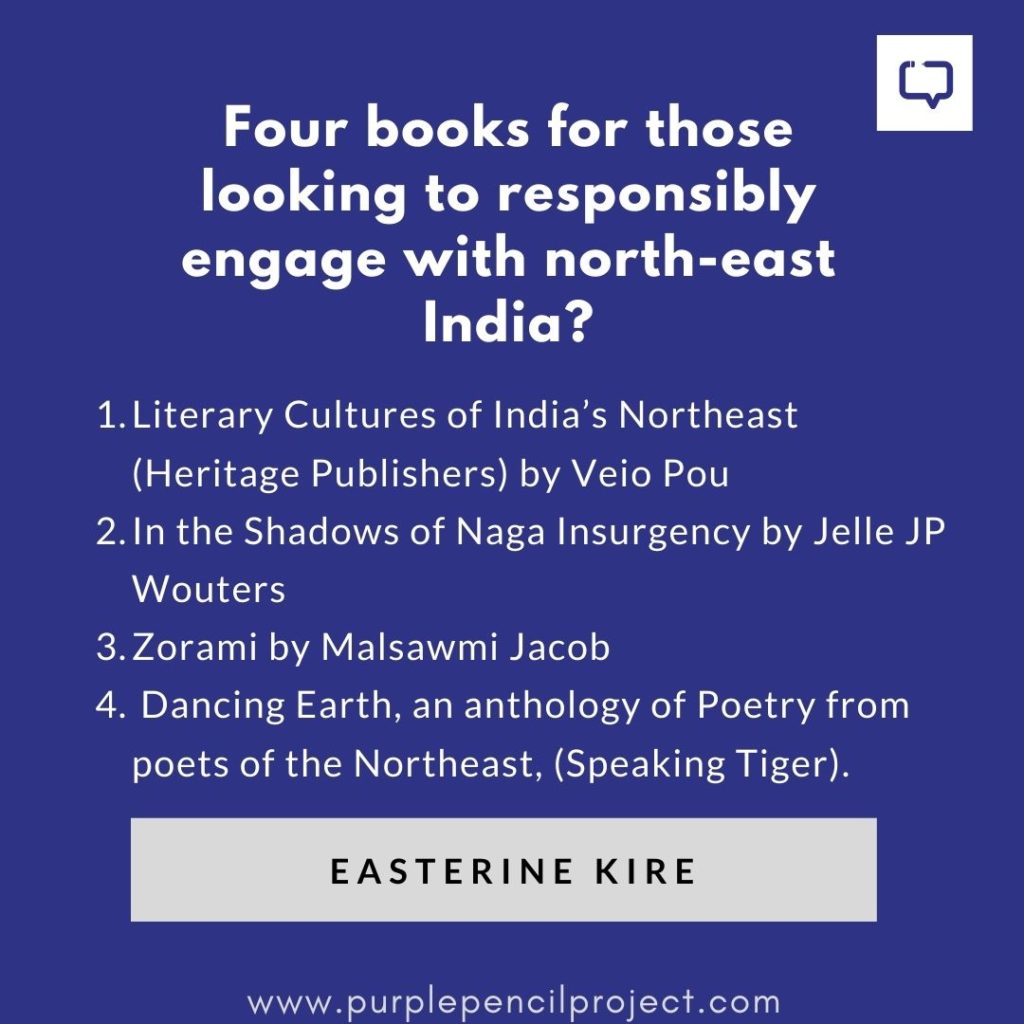

Tenyidie writers have been writing novels, plays, novellas, and non-fiction from as early as the 1940s. Their works haven’t appeared in translation, except for a novella of Dr Shürhozelie (The Vigil) published by Katha. Male voices are emerging in Naga literature and these bring a very different perspective to Naga writing. I think emerging male voices like Lhutu Keyho, Veio Pou, Kezha Whiso, deserve a wider audience. Amongst native writers, I recommend translated works of Dr Shürhozelie. I’m not sure if translated works of Tenyi novelist Neisevituo Sorhie are available.

As to your question on versions of epic literature, I can only speak for Tenyidie literature, that I haven’t come across epic literature in the vein of Gilgamesh or the Ramayana.

What does contemporary fiction look like in Naga literature, or recommendations of fiction based in Nagaland? How has it responded and is responding to the political realities and crises in the region?

Easterine Kire: People outside the region of the Northeast make the mistake of presuming that our literature is homogenous and that we are all writing on the same theme of political unrest. Very far from the truth.

There is a great deal of non-fiction writing produced by scholars such as Charles Chasie, Arkotong Longkumer, Along Longkumer, Abraham Lotha, to name a few, on the realities of the Naga political crises. These titles will be very educative for any writer to understand the problem better.

Most of the young fiction writers are more concerned with life and society, and they highlight social problems that need reformation. I find the younger writers like Anuo Mepfüo, Avinuo Kire, Emisenla Jamir and Theyie Keditsu bravely giving voice to the complications of being born female. It shows that life in Nagaland is much more than the external political situation by which outsiders define it. It is vibrant and challenging, and multi-faceted.

It is not right to expect only political themes from our writers: that would clip their wings considerably. I usually explain that we, writing from the hills, have the backdrop of the hills of history, culture, religion and politics behind us. They are there in our writing, but they are the background, not the foreground, they are indelible, but we let them play (in Bollywoodese) the side part, not the main part.

The story of Khonoma and its people evoked intensely familiar emotions within me. – feeling the need to keep old ways, the need to protect our land, and our culture – while also recognizing that there is a need to step back and see what’s good and worth keeping and what’s not. You have also mentioned before that change need not be a complete replacement. How does one discern what to keep and what not? Is nativised Christianity in Nagaland a response to this thought?

You have mentioned that you try to write about Nagaland’s history chronologically. How do you pick the moments and periods in time you want to talk about?

Easterine Kire: Khonoma is an incredible place with an incredible history. The terrain is rocky and the rock-like character of many of its heroes brings forth the things you mentioned – ‘the need to protect our land, and our culture.’

The old story keepers have done an excellent job of instilling the teachings of our culture to the generations that listened to them. If you go to a Naga village today, the habit of listening to the elders is still in place. It’s a wonderful habit, because these carriers of history and cultural teaching, are imparting a philosophy of life distilled down the ages. In that direction, there is much of the old teachings that should be retained for the good of the community.

An example is the concept of respect. Respect forms the core of Tenyi culture: respect your elders, respect human beings, respect the disabled members, respect the natural world and take care of it, respect the animal world and respect the spiritual world. Change is already present in our lives through the inroads that technology has made. But we are striving to retain the old values because many still believe that abandoning the world view of our ancestors will end in self-destruction.

We could possibly see nativized Christianity working towards that, but I was thinking more in terms of how the Christian symbols were seen to have corresponding symbols in the Old religion, and how Christianity substituted the chicken sacrifice with the sacrifice of Christ. The first Tenyimia Christians accepted that Christ’s sacrifice made all other sacrifices unnecessary. They found affinity between the ten commandments and the taboos of their old religion, and in this way, a gradual nativitisation of Christianity took away the alien nature of the new religion.

I have written on Naga history chronologically. When I was talking to oral narrators early on in my writing career, I noticed that they always used historical battles as time markers.

They would refer to wars and battles and comment that they were born before or after a certain battle of their village. The Zimbabweans also do this with the railroad and my Zimbabwean friend was told by his illiterate mother that he was born the year the railroad was built.

My oral narrators could offer the most information on periods related and connected to these events. I understood how important these periods were to them. It made me decide to cover these historical battle periods and in the process, also give a socio-cultural picture of the community.

I was incredibly moved by Levi’s story, and often wished there we could read more about his happier days, when his sons were young and him and Peno shared a happy marriage. Have you considered adding such details and tangents in your stories which (I believe, and my apologies if I am mistaken) are largely historical in nature?

Easterine Kire: Levi, of course, is fictional, so is his family. I needed someone totally non-historical to move the story forward and engage in the actions which are historically true. Levi is also an archetype of the Khonoma warrior who would have been very active in upholding traditional teaching along with carrying out his warrior duty of defending the village.

I get what you mean of wanting to read more of Levi’s domestic life. I have wondered about the same too. But the reality would be that he was not a stay-at-home dad. Things were always happening outside and he was expected to be at the heart of the action, so to speak. Women were the primary and also the main caregivers in warrior societies like these. I am sure that they, Levi and Piano, were as happy as could be expected living under those circumstances.

Could you speak a little about the storytelling culture that dominated Naga life before print literature entered the scene? Was there a routine of sessions, or were tales narrated in school? Was music or dance intertwined with these stories? What form did storytelling take in your childhood? What books did you read, the characters and stories you grew up with?

Easterine Kire: I had the privilege of experiencing both in my childhood. I grew up with my grandparents in their house, by choice. The central point of the house was the kitchen with the hearth and wood fire. Every evening after dinner, we would sit around the fire to listen to grandfather’s tales. Grandmother was also a storyteller, and she saved some stories for the grandchild who would be sleeping in her bed that night. There were a few bookstores in town and I had my collection of comics and storybooks. I read everything I could get my hands on, Enid Blyton’s books, The Pilgrim’s Progress, Shakespeare abridged by Charles and Mary Lamb, Grimm’s fairy tales, Anderson’s fairy tales, innumerable comics, and my grandfather’s volume of abridged Greek classics.

Much story exchanging happened between friends at school or after school. Story was such an integral part of our lives.

My mother was an excellent storyteller and insisted on detail. If she got a detail wrong on the first telling, she would make sure to correct it on the second telling. Storytelling in our context happened in a very natural way, as an intrinsic part of the lives we lived with its slower pace and intimate family times. The glowing hearth was at the heart of the telling.

At school, we used to have special periods dedicated to storytelling by a very gifted male teacher. I don’t think they have continued that practice. The only Naga tribe that incorporates music and dance in their storytelling is the Zeliang tribe and they have some of the most beautiful dances where every gesture is part of the narrative. In my tribe we have a few songs that accompany particular stories, usually sad love stories.

You write across several formats and themes; as a writer, how difficult or easy is that? You also write for children, as a deliberate way, to build stories they can see themselves in – how do you shuffle between these forms (as well as music) as an artist?

Easterine Kire: It’s easy. It’s a luxury that I shamelessly indulge in depending on the mood I am in. I write fiction most days, but there are times in the month when I need to sit in a cafe and write some poetry. So I do that. It’s very good for the soul.

Don’t write poetry for the money, because there isn’t any money in it. Write poetry to feed your soul. You need that luxury.

The children’s books, I usually say I let the child in me come out and play when I write children’s books. In a way I am writing for the child me, and I like this kind of writing which is not dependent on logic. The most unexpected things can happen and yet, the characters take all that in their stride. Pratham is bringing out a book of mine this year and I love the way the artist has interpreted it. Illustrations are key in children’s books and it gives me great joy when I get the right illustrator.

Do you think sometimes only the stories of conflict are carried outside Nagaland? Even in discourses in media, it is folktales or conflict tales or war tales that get the most attention. For instance, I would love to see simply a superhero story based in Nagaland, and its culture, without that becoming the talking point. Would you guide us to such stories?

Easterine Kire: Overly so. I blame certain media houses and TV channels and magazines like Northeast Sun for regularly portraying the region with images of a burning Northeast in order to sell their stories. I go to literary festivals all over India and get asked the question, ‘Is it safe to travel to Nagaland?’ My first reaction (and I always have to pull it in) is a great desire to get to my feet and show them the imaginary bullet wounds I have received from living in the Northeast. But then I remember, just in time, that it is not their fault, it is the fault of the media, and I refrain from my melodramatic response!

Young Naga storytellers are very fond of Korean art forms and identify with it better than with the western. Some years ago, two young Nagas brought out the first graphic novel with some amazing artistic work. I know of an artist, Akito Chophi, who isworking on a book with anime style illustrations. When these works are ready, it will be worth a read. I will, of course, let you know .

Finally, could you share with us a little about your next work/works?

Easterine Kire: I am working on two-three books and two of them give me a lot of joy. One is a collaboration with an artist and a musician, and I can’t tell you more than that because we will go on the road with it. The other is a book that bridges the spirit world and the human world, something that takes off further from When the River Sleeps. The third is a family history book that is commissioned by a German client.

We encourage you to buy the book from your local bookstore as far as possible. If not, please use the links above and support us. Thank you.