There are a few words that will always go together: India, 90’s kids, reading, Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl, Matilda, Harry Potter, and Nancy Drew. These were great stories. Even today, I sometimes purchase a copy of a Secret Seven or a Famous Five just to glance once again into the unending stories of my childhood.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Yet, every time I read them, I remember having a distinct problem: I did not have friends called Ned, Nancy or George or Pam and Jack. I did not think the idea of Ned and Nancy watching a movie at night was very realistic — I was an awkward conventee in a conservative Indian home. And I doubt there were very many stories around that allowed me, an Indian girl, to take fancy trips of the imagination. My imaginations were realities I could not attain.

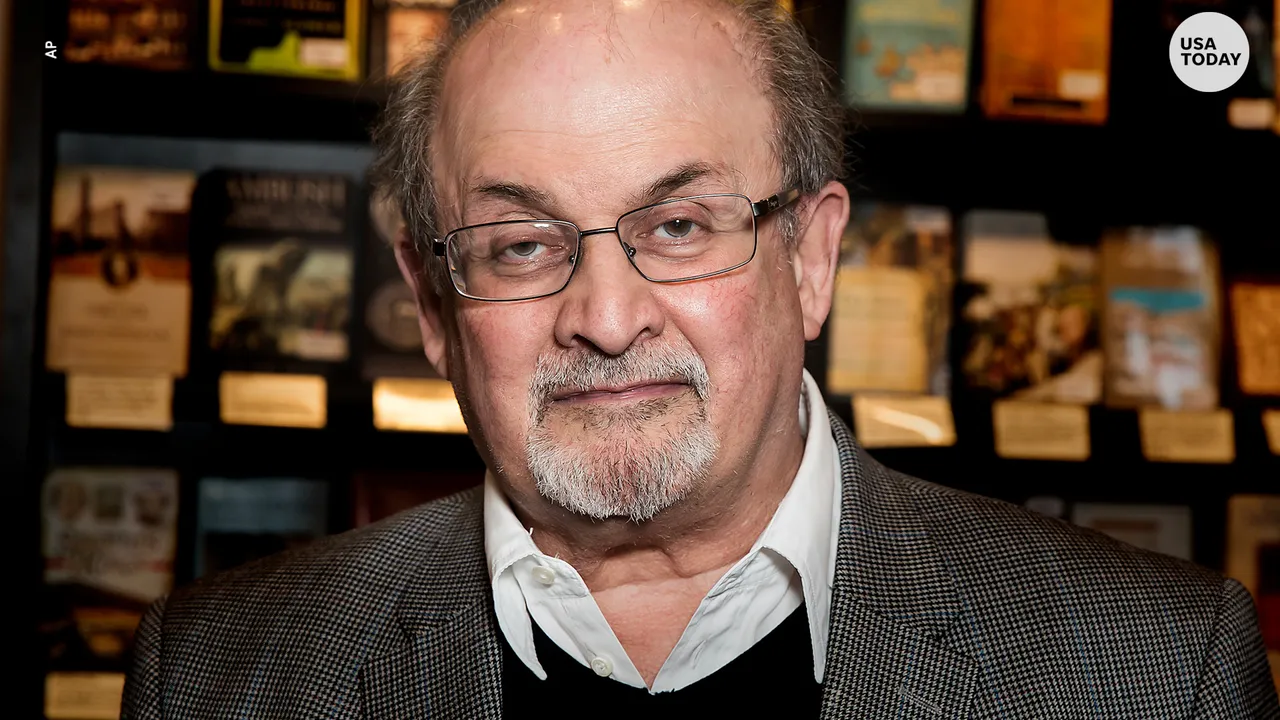

I should have known Salman Rushdie then. Published in 1990, Haroun and the Sea of Stories is a magical Indianized Arabian Nights that involves Rashid Khalipha (the Shah of Blah) and his son Haroun and their adventures through a Dahl-ish world of a sea of stories that are being polluted by Khattam-Shud (which is hindustani for ‘the end’), a power-hungry hater of words and lover of silence.

The story is populated with outlandish, rhyming dialogues, a Water Genie called Iff and a hoopoe called Butt. Iff wears a turban and ‘aubergine pants’ which are very like the patialas sikh men wear. Haroun travels to Kahani, a second moon orbiting earth so fast that we cannot see it. There, the fractions of Gup and Chup are waging a war to save the Ocean of Stories and the Princess Batcheat (yes, baat-cheet which is hindustani for chitter-chatter) betrothed to Prince Bolo (or Prince ‘talk’)

It reads well and could make for a great stop-motion animation video (has anyone tried it yet?) I can hear the sound of shehnai playing as the father-son take on their adventures of a night. I can imagine myself reading this to my little sister as a bedtime story that continues over days. I can imagine little kids enacting it as a drama.

Is this a dazzling, flawless book? Not by any measure. There is the unnecessary capitalisation of words that feel forced (words like Love and Steam which have no larger significance as characters), and there is inconsistency in parts of character traits. For instance, Haroun, after his mother runs away with their neighbour Mr Sengupta at 11 o’clock, cannot focus on anything for longer than 11 minutes. Not only does this trait seem irrelevant and stupid, but it crops up every now and then as if Rushdie always added it as an afterthought. The editor should have caught this. The references are too direct, and sometimes a little unimaginative.

I have a small problem when Rushdie writes – Haroun wasn’t one with the most scientific mind. Yet Haroun is the one asking questions, pointing out logical inconsistencies and being the overall voice of reason. By saying he didn’t have the most scientific bent of mind, he not only enforces the stereotype that a storyteller must be vague and unclear but also skews the very definition of the term. It was 1990, and that may have been an obvious sort of classification, but I can’t seem to forgive it. If a child were to read it, he would, like a lot of us Indians, juxtapose stories and science at opposing ends and if the 21st century has taught us anything, it is that subjects and the lines between them should not be rigid.

But that’s me and that’s my 23-year-old self speaking. Kid me would have just enjoyed being on Kahani. It’s highly recommended, especially for children of the Indian subcontinent.

Favourite Quote:

“I don’t believe you Guppees could keep a secret to save your lives.”

“We could tell secrets to save our lives.”

Recommended Age Group: Can be read to all age groups. 6+ if your kid’s a reader.

Sakhi is a student of literature, an aspiring writer and a partner at www.purplepencilproject.com. She has a degree in journalism and is pursuing her master’s from Mithibai, Mumbai.