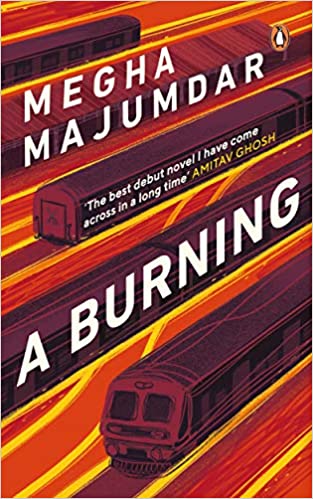

Although a novel that opens with a train burning might somewhat naturally bring to mind the Gujarat pogrom following the Godhra train burning in February 2002, Megha Majumdar’s acclaimed debut, A Burning, does not deal with the complexities of a rioting state. Instead, Majumdar uses the incident of the train burning as a point of departure to focus on the interconnected lives of three characters, their personal objectives guiding the narrative set in the atmospheric metropolis of Kolkata, as the country leans dangerously into the right-wing territory.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Beginning A Burning

A Burning is told primarily from the perspectives of Jivan (a Muslim girl who lives in a slum and works for Pantaloons but is arrested and jailed under suspicion of being a terrorist), Lovely (a poor hijra who aspires to be an actress), and PT Sir (a school sports teacher with political aspirations). Although the chapters are short and quick to get through, switching from one character to another, Majumdar’s style remains somewhat choppy and unpolished, at times reading more like a draft than a final manuscript. However, there are times when the simplistic style works very well, particularly in the latter half of the novel.

The first few chapters of A Burning are quite possibly the roughest sections, as we see Jivan arrested for a casual comment on Facebook regarding law enforcement negligence during the train burning which killed some hundred people.

As Jivan attempts to cope with the legal proceedings of her case, we are introduced to PT Sir (who used to teach her in school) and Lovely (to whom Jivan gave English lessons, as they lived in the same slum). The pacing is on the uneven side throughout the novel but is especially so in these first few chapters, where the writing style is relatively inconsistent and lacks incisiveness, and the prose can be somewhat heavy-handed with misjudging emotion.

For example, when she is arrested in the initial chapters of the novel, Jivan sees a group of boys returning from a nightclub and deduces that they are rich and powerful, possessed of a kind of influence that renders them invincible to any kind of criminal prosecution. While she may well be right, this kind of judgement feels slightly blunted and ineffective, and the comparison doesn’t quite land.

However, these issues gradually become less conspicuous, and the novel picks up momentum as well as a sense of direction when Jivan (in jail) begins to tell a journalist about her struggles with poverty growing up, in the hopes that printing the story of her life will prove her innocence.

It might be interesting to consider how the novel might have been different had Majumdar begun it from this point onward, as when the novel initially begins with Jivan’s ‘crime’, it seems to lack a sense of tension or urgency. Regardless, from this point on, things pick up speed, and the narrative flows much more smoothly.

Class and Characters

While Majumdar portrays the city very well and it works almost as an extra character, with vivid, minor details that create a strong sense of place (from disgruntled guava sellers and political rallies held in fields, to crowded local trains stuffed with irritated passengers), the three main characters juggle the narrative between them. While Jivan is placed somewhat at the core of the narrative, and her emotional progress is charted through the novel as she is led from crisis to crisis, Majumdar’s writing really shines when she is dealing with the moral complexities that confront Lovely and PT Sir.

Lovely has been abandoned by her family and embraced by her hijra sisters, and she comes to realise that the only way she can achieve some success as a film star is to forgo any hope of defending Jivan, whom she knows to be innocent. Simultaneously, PT Sir, who accidentally finds his way into politics and soon becomes the confidante of Bimala Pal (a major player in the saffronised Jana Kalyan Party), realises that he, too, must condemn Jivan if he wishes to retain his position.

Both characters, like Jivan, are to some degree (Lovely far more than PT Sir) products of the status quo and class inequality. Lovely is regularly forced to confront her lack of cisgender and class privilege, while PT Sir desires the respectability and social acceptance that comes with wealth and power. Although the novel contrasts Lovely’s empathetic (and unfulfilled) desire to do right by Jivan with PT Sir’s gradual transformation into a corrupt bigot, the intense psychomachia that both characters face, acknowledging that they are sacrificing their moral principles for the sake of social mobility, is the greatest strength of A Burning.

While the novel does deal with issues of gender and religion (through the character of Lovely and through Jivan’s experiences in a women’s prison, as well as through incidents such as the ‘beef-lynching’ PT Sir witnesses in a village), A Burning seems to be most strongly built around the theme of the class. It highlights how poverty results in powerlessness, and how the consistent desire to rise from ‘lowly’ origins intersects with individual responsibility and morality.

While Jivan is largely in a position that affords her little agency for a large part of the novel, and it is important to recognise that several characters are responsible for her predicament, Majumdar dismantles the notion of collective responsibility to illustrate its inner workings through two characters.

In A Burning, individual choices become important. Although their desires and justifications are hardly identical (Lovely, as a social pariah, must choose between having a livelihood and standing up for Jivan, while PT Sir chooses to quit a steady job and climb the political ladder), both Lovely and PT Sir share a common necessity to ascend in the class hierarchy. While Lovely ensures her security through inaction with regard to Jivan, PT Sir, who wields both social and political ammunition, directly orchestrates Jivan’s downfall.

A Burning in India

Despite the fact that the writing seems a bit uneven at times in terms of style, pacing, and dramatic tension, A Burning makes a commendable attempt to capture the inequalities that riddle India today and the individual apathy that supports it. A narrative that begins with an underprivileged Muslim girl being arrested for an offhanded comment on social media has a great deal of contemporary resonance, especially escalated over the last few months. In many cases, the characters in A Burning lack the social currency or class privilege to speak truth to power, so they are encouraged or compelled to advance corruption, while they benefit from it. A Burning may read a bit simplistically at times, but it is nevertheless a bleak and quietly powerful commentary on the state of affairs in a country that is slowly ceasing to value the necessity of civil rights.

Having said that, its popular critical reception and presence on leading book lists might overestimate its value. Its short and pithy approach leaves A Burning as semi-developed, with mostly forgettable characters and occasional stereotypes. Although it speaks to the present climate in India, it doesn’t really have anything particularly original to offer.

Best Quotes

Paying for the tandoor in a sheaf of cash, he feels rich. He feels powerful in how he casually decides that he will buy it, that he will pay the full amount right away.

Monthly installments are for the common man. He? He has ascended.