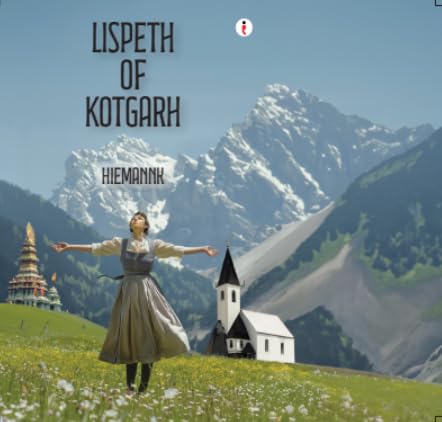

What happens when a literary classic erases you? Hiemannk’s Lispeth of Kotgarh resuscitates a character that Kipling rendered voiceless for 130 years, and Kipling may not even remember.

Lispeth of Kotgarh by Hiemannk is a reimagination of Rudyard Kipling’s short story from 1886, published in November. Hiemannk has not changed the basic plot of the story: it still moves the way it was supposed to, but what he has changed is the agency that the eponymous character of this story now commands.

Reading Kipling’s original Lispeth

Before diving into the details of Hiemannnk’s Lispeth, it is mandatory that we talk a little about Kipling’s Lispeth. Lispeth was born to maize farmers Sonoo and Jadeh, who convert to Christianity in hope of free food to carry them through a rough crop season. A bout of cholera consumes them and their daughter, now called Elizabth (Lispeth is a colloquial bastardization of the name, just as Ramdeyi is of Ramdevi in North Indian villages.)

Lispeth now ends up as a half-servant, half-companion to the Chaplain’s wife, probably because ‘one cannot ask a stately goddess to clean plates and dishes.’ One day she falls in love with a man she saves from certain death. She carries him upon her shoulders, recuperates him back to life, proposes him, only to see him abandon her and go back to England.

‘Being a savage by birth, she took no trouble to hide her feelings,’ is how she is described by Kipling, even though she had been adopted when she was young. When Chaplain’s wife tries to ‘drill some sense’ into her, claiming that the Englishman ‘was of superior clay’ and it was ‘wrong and improper’ of Lispeth to think of a marriage with him, Lispeth renounces Christianity and goes back to her people.

Hiemannk’s Adaptation of Kipling’s story

Hiemannk has written ‘Lispeth’ like a play, adapting it into ‘Lispeth of Kotgarh’. He brings an agency to the eponymous character of his book. Lispeth by Hiemannk is much more a girl than reading Kipling’s Lispeth was.

More gravitas, more heart and more guts. He adds the lost years to the narrative and the decision to write it as a play is thoughtful since it gives voice to a character who was reduced to something little more than a one dimensional personality in the original story.

Hiemannk’s decision to make this a play proves shrewd. By introducing Kipling seeking the aged, alcoholic Lispeth, he positions the original as incomplete. This meta-textual move is bold—when Lispeth sees Kipling, she utters: “Look! Here comes another Englishman to ruin my life!” Readers witness revision, not objective retelling.

Where Kipling grants Lispeth beauty while denying interiority, Hiemannk grants both—and complexity. She’s neither saint nor victim, but a girl navigating impossible colonial hierarchies with genuine vulnerability.

Hiemannk’s most significant achievement is rendering racism visible rather than implicit. Kipling’s original veils cruelty through distance. Hiemannk strips it away. When the Chaplain declares Lispeth may “never be one of us,” or when his wife strategizes using her as propaganda, racism becomes unbearable. The missionaries’ supposed “kindness” reveals itself as transaction and control. This transforms the work into genuine critique.

The Englishman’s casual cruelty deserves praise. He’s not a villain—he’s worse: a man performing complicity. His line, “It takes a great deal of Christianity to wipe out uncivilised eastern instincts,” feels devastatingly casual. Hiemannk reveals something sophisticated: indifference masquerading as benevolence.

The moment Lispeth renounces Christianity—”You have killed Elizabeth. There is only old Jadeh’s daughter left”—devastates because Hiemannk has earned this crescendo. When she reclaims her Indigenous identity, it reads as reclamation, not punishment. The question haunts: Was there ever safety in Christianity, or always destruction?

One flaw: untranslated Hindi passages disrupt momentum. While lending authenticity, the execution feels clumsy. This approach needs clearer signaling.

Ideal readers: Anyone engaged with postcolonial literature, canonical retellings, or representation politics will find substance here. This isn’t comfort reading. If you loved Wide Sargasso Sea, this speaks your language.

Fair warning: This isn’t romantic reimagining. Hiemannk explores devastation, survival, refusal—not redemptive love.

Lispeth of Kotgarh succeeds where many retellings fail. It grants a silenced character choices—even heartbreaking ones. Hiemannk’s achievement is making us understand Lispeth’s rejection of Christianity as rational survival, not naive defiance.

This adaptation demonstrates how revision functions as truth-telling, how reclamation demands discomfort. It’s a necessary dialogue with reading Kipling’s original. Highly recommended for readers seeking challenging, historically conscious literature. Read this, then revisit Kipling; the contrast illuminates what erasure costs.