A compass among rows of paints. The cover of All the Lives We Never Lived is enough to draw you in even without its blurb that promises to be ‘a parable of our times’, whose ‘scale is matched by its power’. It’s scale is vast, but its power, not so much.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

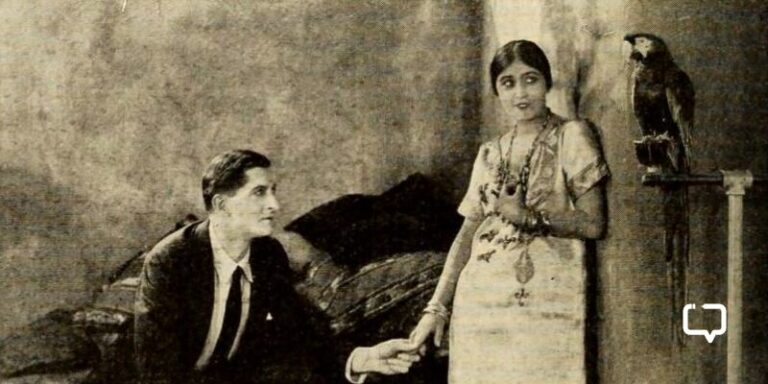

The story begins with the monsoon day of 1937 when Gayatri Chand left her 10-year-old son Myshkin, and her husband Nek Chand behind to pursue a career as an artist, a dream she had harboured since she was a child. Her destination is Bali, her companions are Beryl de Zoete and Walter Spies.

Cut to Myshkin Chand, now an unmarried horticulturist at 60, recollecting the events of his life, growing up in the fictional north-Indian town of Muntazir (Urdu for ‘waiting with expectation’), seeing his house become a pitstop of “appearances and disappearances” of people. It’s a biographical exploration of childhood, often feeling like several blogs put together, and our old guy here is trying to piece them together. His effort is commendable, but not always successful in holding your attention.

What Roy does well with All the Lives We Never Lived is to make her writing intensely visual from the very beginning. There is a scene in which Myshkin describes what it’s like to be without glasses, a burden he’s had since childhood.

Without my glasses the world became a painting of the kind my mother copied at time: dabs of colour against dabs of colours adding up to a sense of a lake with a boat or water lilies in a pond.

The tale woven is elaborate and picturesque to read, switching back and forth between the day his mother left him and the events leading up to that, but feels distant and rambles along for the large part. While the writing is beautiful and (as an award nominee’s must be, lyrical) and while young Myshkin’s pain is real, it is too carefully constructed to have an organic impact.

Walter Spies and Beryl de Zoete and their European attempts at Indology often border on annoying. They play the catalysts, that to Myshkin, drove his mother away, but do not realise their privilege that allows them to do so. Other artists enter and exit this book, leaving their traces, like Tagore, Maitreyi Devi, and Arthur Waley.

Artfully written and bringing history and fiction on the same page, it is a good story without being brilliant. Few scenes from the novel come back to me, like when Lipi threatens to burn the house down or when Myshkin’s grandfather uses the refrigerator, then a novelty, to cool his kurtas before wearing them each morning. Or the actual moment of Gayatri leaving, and Myskhin, restless to get home from school because his mother has asked him to come home “not a minute late” so they may go on a trip together, finding out that she has left without him. It reminds me of a line from one of my favourite songs, ‘Chhhod Aaaye Hum Woh Galiyan’ from the film ‘Maachis’. It has a line: “Ek chota sa lamha hain, jo khatm nahin hota. Main laakh jalaata hoon, woh bhasm nahin hota”. It can be translated to: There is a moment, that never ends. I try to burn it a million times, but it is indestructible.”

https://youtu.be/Y7JRWs9dvVo?t=238

Set against the backdrop of WWII and India’s own freedom struggle, the juxtaposition of the personal, the local and the global is well-thought and mirrors the stifling of expression we face today but executed in a tone that does not quite match. In bringing restrain to her work, Roy may have gone too far, and taken some of its essences away.

It is only halfway through the book that there is a real spark, though a little rushed, in letters that Gayatri had written to Lisa McNally, their former neighbour, whose relatives from Vancouver have now sent them to Myshkin. From here on, the epistolary narrative grips you. We have met Gayatri Sen indirectly, through what Myshkin remembers hearing from his mother. But now, it is time for Gayatri Chand to speak.

***

October 17, 2018, Mumbai

My dearest reader,

As Gayatri is enjoying her freedom, you begin to question the notions of influence, support, and imposition. Freedom is not to be alone. It is to have someone who will help you soar. Gayatri was free with her father, even though she was highly dependent on him. So also Walter Spies (who is mentioned so many times in her letters you begin to wonder if she has a mind of her own. Agreeing with new ideas can sometimes feel like that). Her parents & Nek Chand on the other hand actively discouraged her from being her own woman.

October 18, 2018, Mumbai

Dear Reader,

Have you ever lived in a foreign land? Have you gone through a whole phase of your life without feeling like you belonged? Have you lived with the terror of people you love being taken away? Have you thought you could escape life, but it will come land at your doorstep?

Have you been smitten by escape only to realise, that perhaps for change to happen, running away is not a solution? But that you had to make a journey anyway?

Like a teenager, who realises that they may not be completely ready to handle the freedom they seek. Like Gayatri. Like India in 1947 and the years after. But you need to break away once.

October 19, 2018, Mumbai

Reader, dearest,

So many news for a young woman on an adventure to share, so many facets of her life before and after explored, most of all her friendship with her friend Lisa. To read, even in glimpses, that there were free-spirited women being there for each other even in the 1930s, to hear a free-spirit talk without any filter, is endearing.

***

In these chapters, Roy has a firm grip, portraying Bali, its natural beauty, its isolation and its eventual integration with the War at large with finesse, so much that the rest of the book pales. Not because Myshkin’s story was not important, but because you have seen and heard it often enough.

All the Lives We Never Lived thus becomes the story of All the Characters We Could’ve Met. Like Lisa, Batty, the friendship between Lisa and Gay – needs a novelist’s attention.

Instead, because it is Myshkin’s book we are reading, they have little space. And up until the end, when he decides to make the same journey as his mother, the book is repetitive, relying on the power of language to say the same and similar things over and again, emphasising the same events and emotions so much that you become immune to them. It had the right ingredients, but the wrong recipe, perhaps.

An out and out epistolary format, or a younger Myshkin talking and taking the journey his mother made; two fixes I think might have saved this story.

Favourite Quote:

When the world was in turmoil and devastation appeared inevitable, art was not an indulgence but a refuge, its fragments remained after a cycle had run its course from creation through to destruction and begun again.

Recommended For: 16 and above, and for women trying to find an answer to their lives.

Final Verdict: It is not a must read. But if you are a fan of lucid writing and reading stories painted in words, you should go for it.

Buy the book here.

All the Lives We Never Lived has been shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature and is also on the longlist for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature 2018.

Further Reading:

- Poems by Arthur Waley

- Rabindra Sangeet, to truly transport yourself in Gayatri’s childhood and her fascination for Shantiniketan

- Dance and Drama in Bali, by Walter Spies and Beryl de Zoete

- A little history of Bali

**Author Image Courtesy: Anuradha Roy Blogspot (copyright Francesca Mantovani).